by Jude Vallette // Aug. 30, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Desire.

‘Sentient Clit: the Pussification of BioTech’ is a collaborative project rooted in scientific research and creative dialogue between artists Jiabao Li and Dr. WhiteFeather Hunter. Hunter, a Canadian artist and researcher, merges the realms of “witchcraft” and science in her practice, particularly focusing on the potential of female body fluids in advancing biotechnology. Jiabao Li, in her career as an artist and designer, explores sustainable futures through a femme-centric engineering perspective, also experimenting with the multitudinous uses of menstrual fluid.

The result is a multimedia and immersive art and research project titled ‘Sentient Clit,’ which mainly centers around bioprinting and engineering lab grown clitorises derived from stem cells found in menstrual blood. With ‘Sentient Clit,’ the pair push forward conversations on female pleasure—an often dismissed subject in the scientific field—while also offering a critique of social attitudes towards sex work, consent and sexuality more generally.

We spoke to Li and Hunter about their motivations for the project, the medical and ethical dimensions of their work and their decision to showcase their project in both traditional art exhibitions and unconventional platforms, such as Only Fans, as a means to reconsider how we think about pleasure.

3D bioprinted clitorises seeded with cardiomyocytes, produced by Montreal collaborators, 2023 // © WhiteFeather Hunter

Jude Vallette: How did your collaboration on this project come about and how did the idea of 3D printing stem from your research?

Jiabao Li: Both of us have been working with menstrual blood for a while. I focus on the proteome within menstrual blood, analyzing the proteins it contains. We both shared our work online, which is how we discovered each other’s research. It felt natural to collaborate since we are both “menstrual witches.”

WhiteFeather Hunter: Yes, I started working with menstrual blood as a biomaterial during my PhD research, exploring its potential in tissue engineering. After receiving a generous grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, I was invited to experiment with a 3D bioprinter in a new lab in Montreal. Around that time, Jiabao and I connected, and we developed the idea of 3D bioprinting clitorises using the material we were both experimenting with. The project was also inspired by a new discovery in 2022 that revealed snakes have two clitorises. We thought, why not explore this further by creating more clitorises?

JL: That discovery highlighted the importance of the clitoris in snake mating, emphasizing that it’s about pleasure, not just reproduction. This made it a significant organ to focus on.

Jiabao Li: ‘Sentient Clit’ // Courtesy of the artists

JV: Can you elaborate on your choice to showcase and distribute parts of this project on OnlyFans? What motivated this decision, and how has the reception been?

JL: We wanted to break out of the traditional “white wall” museum space and push our work beyond the art world. Given that our project revolves around the clitoris, a lot of our discussion naturally touches on the consumption of the female body and feminist themes. Since we were talking about consumption, we decided to take it to the extreme by presenting it on a consumption-based platform like OnlyFans. We might even explore Pornhub later. We’re still in the process of uploading more content and getting the story out there, and so far, it’s sparked quite a bit of discussion, especially on Instagram.

WFH: Yes, we’ve encountered our fair share of trolls—”dude bros” who are not shy about expressing their opinions. But this decision is part of a long tradition of feminist performance art, where women take control of how their bodies are presented, both sexually and otherwise. There’s a precedent for this; for instance, when I was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a fellow artist named Janet Lin was making spoof porn on interactive sites back in 2010. She faced a lot of criticism, but her work influenced my thinking around using platforms considered to be part of sex work. Jiabao and I decided to enter this realm to disrupt the conversations happening there around the consumption of women’s bodies and the male gaze, and to adapt those conversations to suit our own needs. It’s a fun yet meaningful way to engage with these topics.

Jiabao Li: ‘Sentient Clit: the Pussification of BioTech’ // Copyright WhiteFeather Hunter and Jiabao Li, courtesy of the artists

JV: How do you hope to change the narrative on sex and pleasure in a biotech-capable world through your project? What ethical questions do you hope the public will explore as a result?

WFH: Scientifically and biomedically, our work stems from a desire to evolve the conversation around reproductive health. Sex work and reproductive health are deeply interconnected, yet women, especially sex workers, are often excluded from these discussions. Typically, reproductive health discussions focus on reproduction, sidelining the topic of pleasure, which is a crucial aspect of our lives. We want to broaden the conversation to be more inclusive and representative of all women and femmes. If you look at the comments on Jiabao’s Instagram post about our project, you can see the resistance to even acknowledging female pleasure as important—there’s an aggressive dismissal of it. That’s been eye-opening.

JL: This project has also been a form of sex education for me, personally. Growing up in China, I had no sex education at all. When I visited a penis museum in Iceland that showcases penises from various species, I was struck by the absence of a vagina or clitoris museum at that time. This highlights a significant imbalance. After we showcased our work, people began discussing issues like genital mutilation, raising the possibility that our work could lead to advances in genital reconstruction. So, we’re addressing that aspect as well.

WFH: Exactly. There are many potential applications for our work, though we’re still in the research and development phase. We’re not presenting this as a solutionist project, but rather as a way to instigate dialogue. As Jiabao mentioned, it’s part of sex education. In most sex ed classes, the clitoris isn’t even mentioned—conversations are solely about reproduction and women’s roles as mothers, with female pleasure being downplayed or ignored entirely.

JL: To put it into perspective, the correct anatomy of the clitoris was discovered 29 years after we landed on the moon and after we had already mapped out the human genome. That’s a significant delay in understanding such an important part of the female body.

Jiabao Li: ‘Sentient Clit: the Pussification of BioTech’ // Copyright WhiteFeather Hunter and Jiabao Li, courtesy of the artists

JV: Speculatively, what does desire mean for the sentient clit?

JL: You’d have to ask the clit!

WFH: We’re currently experimenting with differentiating stem cells into neurons, which raises fascinating questions. Could the clitoris form thoughts? Could it dream? And if it’s in a Petri dish, is it wet dreaming? These are the fun, speculative questions we’re exploring. I recently presented this work to a group of medical researchers, and a neuroscientist suggested that the best indicator of whether the neurons are interacting would be if they’re firing. So, our next step might be to differentiate menstrual stem cells into neurons and measure synaptic activity. Once the neurons start firing, we’ll have even more to think about.

JL: One of our ideas is for the clitoris to play Tinder. Scientists have already proven that a human brain in a dish can play the game Pong, so why not have a clitoris make choices? There’s a saying, “Men think with their dicks.” So we’re exploring the idea of literally thinking with a clit.

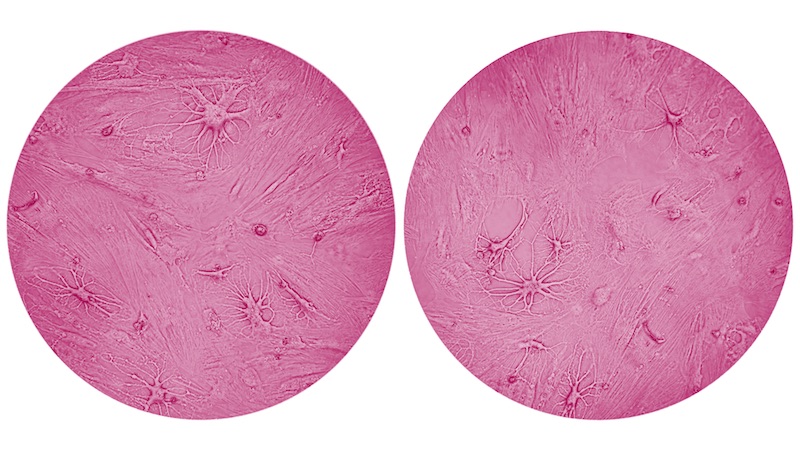

Astrocyte pair, recoloured, used for wall murals in the display of ‘Pussification of Biotech,’ part of the ‘Progenitorial Hysteresis’ exhibition by Jiabao Li // Copyright WhiteFeather Hunter

JV: Did you face any difficulties in receiving funding for this project?

WFH: On my end, I received funding from the Canada Council for the Arts and regional arts funding in Quebec. I’m fortunate to have access to this support as a Canadian artist. Jiabao has her own lab, which provides flexibility.

JL: Yes, my university research funding is non-restricted, meaning I can pursue any project I choose, which I’m very appreciative of. This freedom is crucial for doing this kind of work.

Jiabao Li: ‘Sentient Clit’ // Courtesy of the artists

JV: How do you envision it contributing to medical advancements?

WFH: While biomedical applications are possible, our primary focus has been social critique. However, it’s entirely possible that this work could be developed further by a biotech company or a university. One speculative idea I’ve had is to implant a clitoris prototype in my forearm, inspired by Stelarc, a performance artist who implanted an ear in his arm. Jiabao even joked about implanting it in the palm of our hands so that during a business handshake, no one would know what they’re actually touching.

JL: There are serious biomedical applications as well. For example, people who have undergone genital mutilation or transgender individuals could potentially benefit from clitoris transplants, maybe even using tissue from a partner or friend. More generally, we hope our work will encourage more research into menstrual stem cells, which are still relatively understudied but have huge potential. Instead of freezing eggs for reproduction, why not freeze menstrual blood? It’s something we “waste” every month, but it could potentially save our lives later. Imagine using your own menstrual stem cells to repair a broken heart or brain—how beautiful would that be?

WFH: Exactly. Menstrual stem cells are under-researched, and they’re institutionally treated as biohazardous waste. By reframing menstrual blood as a resource instead of waste, we’re challenging the stigma around menstruation. Recent research shows that menstrual stem cells might be superior for regenerative medicine, like repairing heart tissue after a cardiac event or treating Alzheimer’s. This could be a game-changer.

JL: It’s exciting to think about the possibilities. Menstrual stem cells could revolutionize how we approach health and medicine.