by William Kherbek // Sept. 27, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Accessibility.

melanie bonajo is a video artist, somatic practitioner and sex coach whose works have incorporated a wide range of aesthetic and social discourses. bonajo, alongside Yanna Rüger and Daniel Cremer, and Theater HORA—an ensemble of stage actors and artists based in Zurich who also live with cognitive impairments—recently created the work ‘School of Lovers.’ The multi-media piece explores the ways in which comfortable spaces of articulation can be ensured for differently-abled populations, specifically in relation to topics and engagements around sexuality and intimacy. Realising such an inclusive and embracing work requires a focus on mutual recognition and trust. We spoke to bonajo about the ways in which the artist and their collaborators negotiated different challenges to create a theatre and video work that was at once participatory, instructional and deeply personal.

melanie bonajo, Theater HORA, Daniel Cremer, Yanna Rüger: ‘School of Lovers,’ 2023, video still // Courtesy of the artists

William Kherbek: Could you take us into the origins of the ‘School of Lovers’ project? How did you think about notions of ability and desire in conceiving the project?

melanie bonajo: Well, first of all, it’s a collaborative project. It was made together with Yanna Rüger and Daniel Cremer, and the biggest collaborator was the Theater HORA. They had a big voice in the writing of the whole piece. The result is a theatre show and video, and those are also accompanied by workshops. We started a school, the ‘School of Lovers,’ and together with the cast of Theater HORA, we made a curriculum, which is based on somatic sex education and sexological body work that includes notions of intimacy, the body, sexuality, language and boundaries, and we translate this to a level such that people with a cognitive impairment can have access to these teachings.

In a way, talking about desire, it feels already, for me, very much an ableist question, because that’s already too far. In order to make this curriculum of sex education, we needed to make it as accessible as possible, as simple as possible. Bring it down, really, to the core of the core of the core, and then repeat certain exercises that are physically embodied. For example, asking for a certain type of touch, or expressing a boundary.

We also had a moment where people could ask questions, and also where we could ask questions, because it was essentially a co-learning space. We were all teachers and students at the same time, bringing in a vocabulary around gender or anatomy that was unfamiliar to many of the people in the group. We did a lot of role playing, just bringing it into real life situations that were valid and active in the moment. That was something that we committed to for one week. Out of that process, we extracted the most essential points of learning and the ones that kept the most attention and seemed to have had the most value, and from that, this piece is constructed.

melanie bonajo, Theater HORA, Daniel Cremer, Yanna Rüger: ‘School of Lovers,’ 2023 at ShedHalle Zurich // Photo by Laila Kaletta and ProtoZone13, Shedhalle Zurich, 2023

WK: In terms of exploring these quite intimate questions in a public format, what was the process for getting people to open up?

mb: What we do is we create a trajectory of opening up, like peeling off the layers, going step by step. These are social tools that involve the body, and your private space and your public space. Through a certain set of exercises, we take people through a journey of softening, and finding more vocabulary and awareness around desires, needs and boundaries, through which they feel the safety to authentically navigate pathways of connection that are accessible all the time. If we had the tools to access them and if we had social agreements that we all practice, that would make these paths visible for everyone.

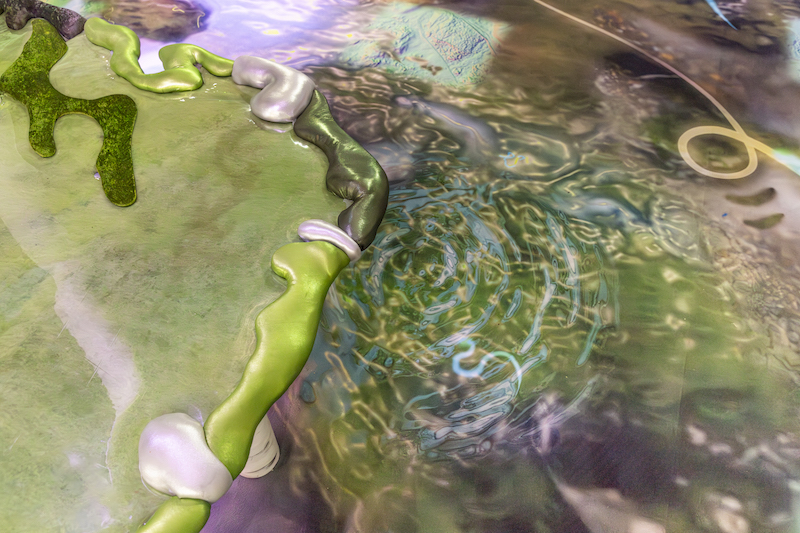

melanie bonajo, Theater HORA, Daniel Cremer, Yanna Rüger: ‘School of Lovers,’ 2023, video still // Courtesy of the artists

WK: What were some of the most effective tools that you felt like these workshops gave rise to, or made people aware of?

mb: One of the tools is arriving in the body. We do a lot of exercises around arriving in to your own space. And this you can do through physical exercises like shaking or dancing or stretching, or just moving into the space. [We do this] just to give everybody a moment to be with themselves in their body through movement.

And just by being in silence and having different exercises for how to connect to different sources of information inside your body, you can see what they have to say to you in this very moment. Then there were a lot of exercises around proximity and how to actually sense what feels good to you about proximity in that given moment, with that given person or that given group.

We do things that happen in normal situations with people in intimate settings, but we slow them down so you have more ability to observe what is happening in your body as a signifier of what you actually want to decide at that moment: what is good for you, and for the others. So it’s a rehearsal space, and it’s a space of slowness and details, and having the option to really embrace that space of slowness.

WK: It seems like humour was a useful device for allowing people to have a different relationship to these topics.

mb: Yeah, definitely. I also think that because it’s presented as a school, in which we are all students and teachers, it also breaks this hierarchy of “we know how it works and you don’t.” It gives everybody the chance to be messy, or to show up with flaws, and to know that we are all capable and incapable around these subjects. So this also already gives a space of just loosening up and not taking it too seriously and just giving it a chance.

melanie bonajo, Theater HORA, Daniel Cremer, Yanna Rüger: ‘School of Lovers,’ 2023, video still // Courtesy of the artists

WK: How did you originally begin working with Theater HORA group for the project?

mb: It was an assignment. They asked me. I had worked with them before in a “lab” kind of way, doing our workshops, but this was the first time that, together with Daniel and Yanna, who works there permanently as a director, we worked towards a piece together. There was a lot of new things that I learned. They’re extremely professional. It was very impressive. They have a beautiful manifesto online of how they want to work, and this manifesto is, in essence, very anti-capitalist. So it’s not based on production and goal-oriented approaches, but it includes a lot of things about conflict resolution, and asking “what are the needs within the group” and “how are we all feeling?” It has a slower pace and takes more attention to detail. No emotions are being repressed or bypassed. For example, every morning there was a check-in. We don’t work for too many hours, and then there’s always a checkout on how the day was. So there was a lot of attention to whether everybody personally feels good and whether the group cohesion is good, and we reflected on what we’ve done and where we want to go, and what worked for everyone (and what didn’t). Nothing is swept under the rug. It really felt like that: everyone was so respected and given so much space. These were really things that I would like to keep in all future productions, with anyone I can.

WK: I guess it’s quite an iterative process making something like this work.

mb: Yeah, definitely. But it’s possible. It’s not that much more effort, but it is just a little bit more effort. It’s not so difficult to build a ramp [for instance]. It’s just a matter of priorities and it’s about welcoming. Who is welcome in your space? Do you want to welcome everyone in your space, especially if you’re a public institution, or are some people not welcome? Who is missing in your space? And that’s your responsibility, to think about who you welcome and who you do not.

melanie bonajo, Theater HORA, Daniel Cremer, Yanna Rüger: ‘School of Lovers,’ 2023 at ShedHalle Zurich // Photo by Laila Kaletta and ProtoZone13, Shedhalle Zurich, 2023

WK: For people who are interested in exploring these subjects in greater depth, what are some of the key things you would say you’ve derived from this long-standing period of your practice that people could bear in mind, or should think about in terms of making creative spaces of accessibility and regarding inclusion?

mb: There are a lot of practical aspects: create meetings, where you invite people with various disabilities and let them speak about their needs, and design the accessible space with them. There’s also a lot of social arrangements, and this also really big, because a person with physical limitations can have such different needs than somebody with a cognitive impairment. You can’t really put it all under one umbrella. It needs commitment and the attention of the institution, because you can’t really say there is one “Disability.” It’s a very wide spectrum of different things.

If I work with a specific group, every time [I am] specifically forming a method related to this group, and making a language that is inclusive and really welcoming, by being mindful about where internalised ableism might pop up in the way of formulating sentences. Institutions also need to take care to compensate accordingly financially. When giving a mixed group workshop, it is important that the groups are really mixed and not just open for people living with disabilities. This is part of the work. Make yourself trustworthy, so that this group feels safe with you. We spend a lot of time making space, creating trust and a safer environment that promotes arrival in equality, entering a territory together where everyone can meet on an eye-to-eye level and as an equal, and the work to make that happen is on the ones who have more privilege.