by Dehlia Hannah // Oct. 25, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Accessibility.

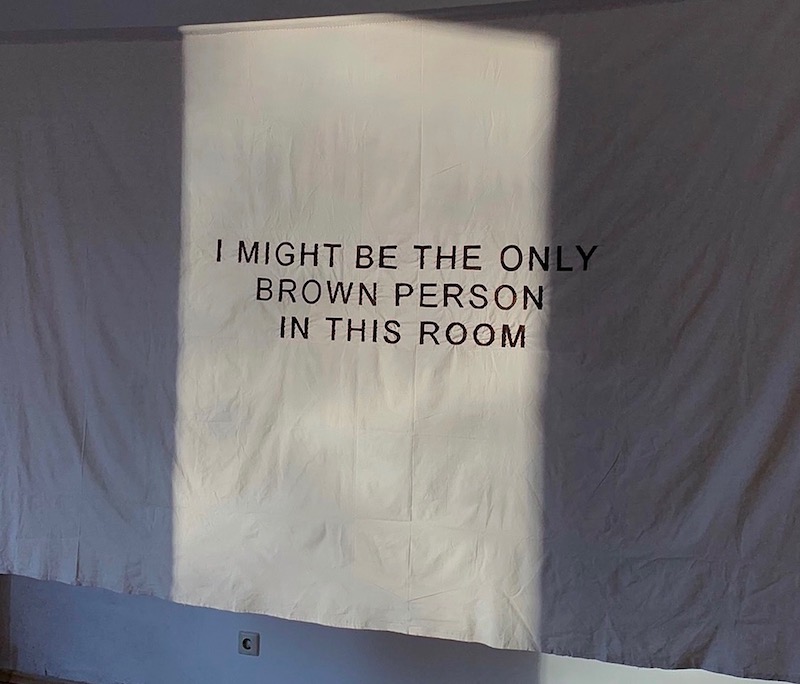

“I MIGHT BE THE ONLY BROWN PERSON IN THIS ROOM” read the black block letters meticulously embroidered on unbleached cotton, whose unfinished edges recede into the white wall of the gallery. Reading these words, I immediately recognize that I myself had brought Carla Abilés into many such rooms, in which she noticed something that I did not. The work, created for the exhibition ‘Uprootings and Reconnections’ at Bardo Projektraum in Berlin last March, confronts me gently but insistently with the reasons for my unnoticing. Perhaps it is because in museums and galleries, biennales, homes, restaurants, playgrounds and parties in Berlin, unbroken homogeneity is a norm that it seems almost rude to disturb. This I perceive, not because I too am brown, but rather another shade of unbelonging. Born of other migration histories, it follows me like a shadow, which I at once fear and hope someone will notice. Perhaps, in my feeling of kinship in a sense of alterity, I resisted noticing unspoken differences. Abilés gives voice to such reflections in a medium almost too slow for words.

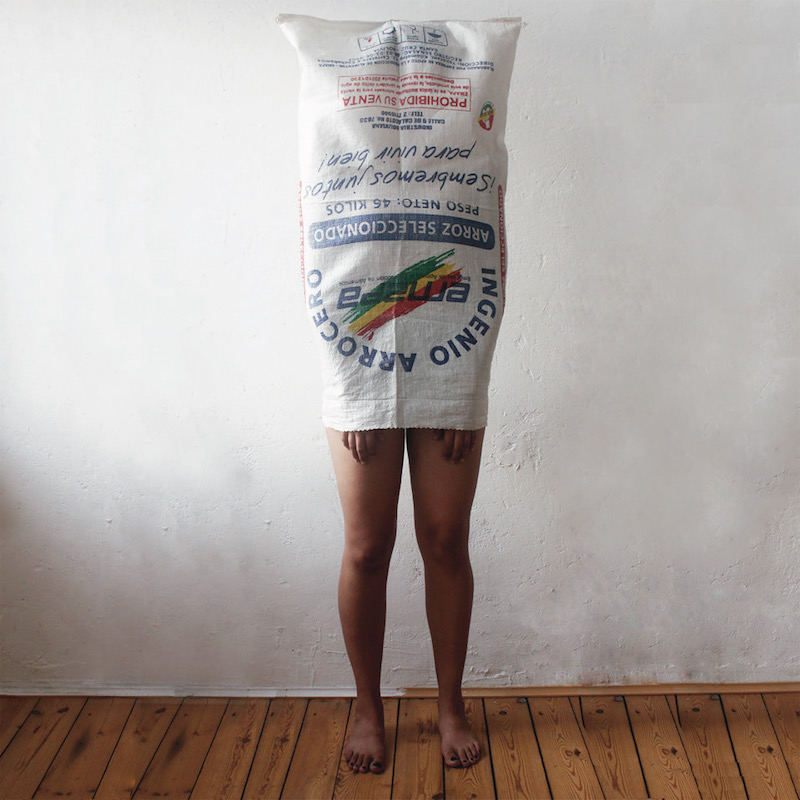

Carla Abilés: ‘Falso Conejo,’ 2020, digital photo // Courtesy of the artist

In a moment when fully formed sentences give way to abbreviations and emojis, embroidery evokes the tactility and endurance of social relations that lay at the foundations of the art world. Her presence—and more often her absence—in these spaces frequently made my own possible. As a curator and academic with two small children, I depend on the labor of others to allow me to participate in the art world; to be out at night, to travel, to have time to think at all. Those Others are more often than not women from the Global South. Others, with whom I share not bare responsibility but some of the most intimate aspects of my life. Others, whose labor time I can afford.

Carla Abilés: ‘Premisa,’ 2024, embroidery on cotton fabric, 250x150cm // Courtesy of Bardo Gallery

A growing list documents ‘Todos Los Trabajos’ (All the Jobs) that Carla Abilés has worked since moving to Berlin from Salta, Argentina in 2020, at the start of the pandemic: Dish Washer. Cleaning Lady. Prep Chef. Asistente. Call Center Agent. Baby Sitter. ‘Up Until Now’ (2024-Ongoing) presents an artist’s resume embroidered on microfibre cleaning cloths, the soft and staticky material of which is designed for limited reuse. Unwelcome to the touch, this substrate for the painstaking work of embroidery evokes the conflicting affects associated with care work, in which genuine emotional connection, attention to detail and bodily receptivity to touching and being touched constitute the “heart” of the job.

Carla Abilés: ‘Todos los trabajos,’ 2024, embroidery on cleaning cloths, 25x25cm // Courtesy of the artist

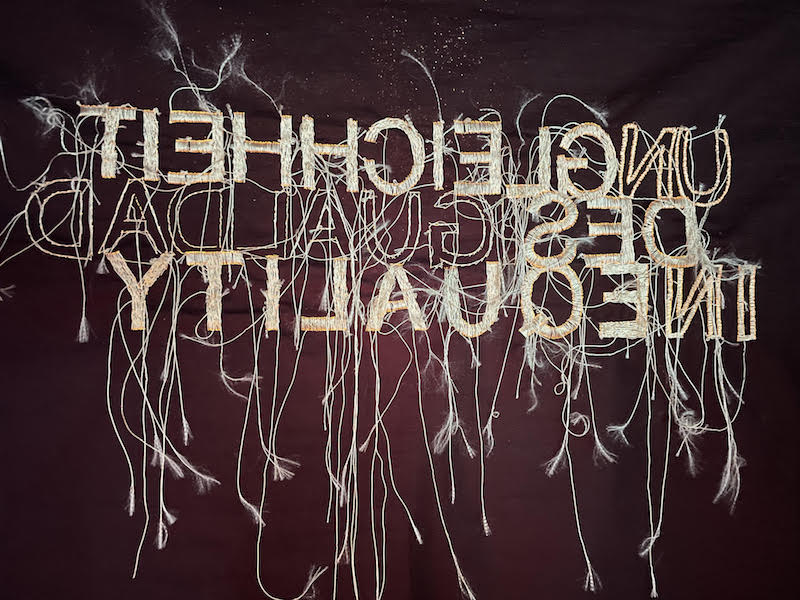

Access to participation in making and working with art depends, fundamentally, upon the stratification of wages. This determines who works for whom in an economy of mutual needs. It is not just a matter of making a living (or even of affording artists’ studios and supplies), but of working under conditions that allow creativity and intellectual acuity to thrive. At a minimum, such conditions include a living wage, an ambiguity that presents a major challenge in the realm of unregulated work performed by a labor force rendered daily more “flexible” by geopolitical turmoil and the long arm of neoliberal dispossession. But other conditions matter too; whether inspiration may flourish alongside, or even in spite of, pervasive inequality (addressed in a 2022 work exhibited at Oyoun) depends upon a host of factors, at once deeply personal and thoroughly social. These implicit conditions determine whose questions will be expressed, whose voices will be heard, which techniques and materials will be developed as Art, and ultimately, whose class, gender, ethnic and cultural perspectives shape a contemporary space of ideas.

Carla Abilés: ‘(In) Equality,’ 2022, embroidery on black cotton fabric, 120x80cm // Courtesy of Dehlia Hannah

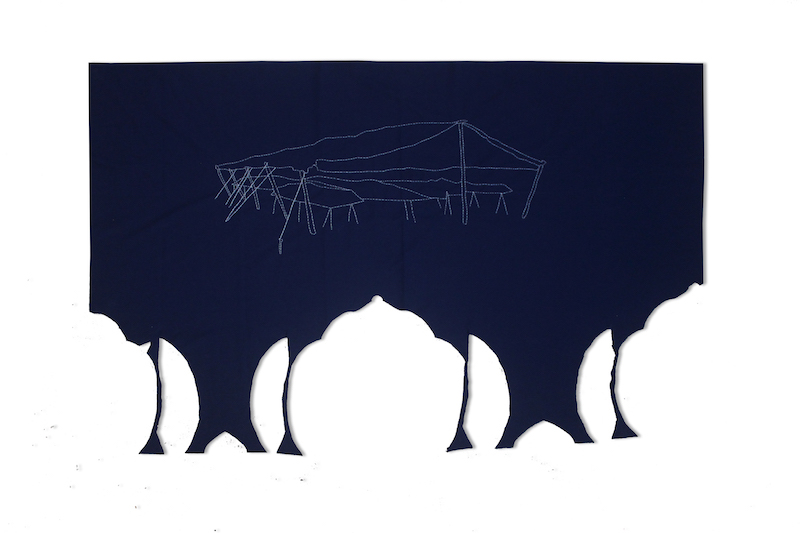

Trabajo (Work) has long been a theme for Abilés, who began working with used clothing and textile scraps from the garment industry during art school, in Salta. With a keen eye for found poetry latent on tags and labels, she sifted through mountains of discarded clothing offered for sale in tents around Northern Argentina, an architectural motif to which she repeatedly returns. As an embroidered image, a picture created by metal nails puncturing fabric, and a sculptural frame draped by the garments typically sold there-in, the tent’s omnipresence holds open a space in which desire and possibility co-exist with desperation and waste. (This waste, the detritus of the North’s overconsumption and a fast fashion industry that circulates value through the hands of largely female garment workers.) An openness to what might be found typifies Abilés’ practice, a patience to discover what may emerge over a slow process of creation. Specific forms of knowledge arise from particular kinds of work, so the Marxist feminist tradition has long insisted. On heavy blue cotton scraps, remainders from the flat pattern cutouts of workers’ uniforms reminiscent of the German Blaumann suits reworked by Simon Mullan (a Berlin artist dealing with class-based masculinities), she embroiders the aphoristic knowledge of agricultural workers: “Trabajo Trabajo Trabajo (Work Work Work) / Quien no trabaja no descansa (Without labor there is no rest) / Mi humilidad perdon tu ignorancia (My humility pardons your ignorance).”

Carla Abilés: ‘Tent,’ 2019, embroidery on textiles waste, 135 x 70cm // Courtesy of the artist

An old photo portrays Abilés in the back of a minibus on her way through Bolivia, the place where, she had recently learned, her maternal grandmother came from; her grandfather was a Japanese immigrant to Bolivia. She is framed by the word “Amore,” painted on the outside of the bus, and hers is a journey of love. Associated with indigeneity and dark skin, her heritage was and remains a source of stigma in Argentina, where complex histories of migration have given rise to a myriad of racial categories. And with them, hierarchies of difference and discrimination cultivated over centuries by church and colonial authorities. Against this historical context, the category of “brown” has emerged as a broadly inclusive term of Latin American political identity. The question of identity and misidentification haunt those whose ancestors have migrated, for all the diversity of reasons that set people on the move. On a large brown plaid blanket, Abilés plays on this familiar propensity for misreading. In the poetry of mistranslation, ‘MIGRAR’ (to migrate) becomes ‘MIRAR’ (to mirror). In the mirror, she (I, you) see a migrant. As the artist states, she did not set out to make art about poverty, race and migration (among other things) but they emerged as “unavoidable themes.” These conditions extend to many migrant artists: indeed, as a participant in HIER & JETZT: Connections (HUJ:C)—a residency and exchange program for artists in exile at BLO Ateliers in Berlin-Lichtenberg—she coped with working in a studio space without electricity for three months.

Carla Abilés: ‘MI(G)RAR,’ 2020, embroidery on blanket, 71×157 // Courtesy of the artist

A focus on accessibility calls our attention to these themes as a latent subtext of artwork even where they are not addressed overtly. Perhaps one arena in which this is most evident is in the barrier to entry that is formed by the distinction between art and craft. Historically, this distinction tracks neatly onto gender and class divisions, with predictable economic implications. With appreciation for the inspiration to her own artistic practice, Abilés is presently involved in the curatorial and production team of ‘Textiles Semillas: A Living Project of Weaving and Bridge-Building,’ where she works with an intergenerational collective of female weavers, artists and activists from Northern Argentina. This week, the project will be presented in the event ‘99 Questions Gathering: On the Poetics of Loose Ends,’ a hybrid program of conference, exhibition and workshops foregrounding knowledge exchange and creative practices of resistance in the Global South.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Humboldt Forum

‘99 Questions Gathering: On the Poetics of Loose Ends’

Exhibition: Oct. 25–Nov. 2, 2024

humboldtforum.org

Schloßplatz 1, 10178 Berlin, click here for map