by Mats Antonissen // Oct. 25, 2024

To celebrate its 40th edition, Interfilm reflects on where it all began. With the ‘Alle Macht der Super 8’ section, the festival pays homage to its precursor of the same name. On November 9th, the Prenzlauer Berg bureau’s basement will host a screening of 11 shorts filmed with Super 8mm cameras. These date back roughly to when Interfilm first took off across town, in Kreuzberg’s squats of the early 80s. Unsurprisingly, Berlin—from its night life to its politics—figures in a good portion of the program.

We talked to Guy Parker, the curator of the special, about the past and present of Berlin, Interfilm, filmmaking, experiment and technology, as well as the program’s significance for the upcoming anniversary edition.

Katarina Peters: ‘Zentri-Fuge/ Centrifuge,’ Germany, 1985

Mats Antonissen: Can you tell us more about Interfilm’s early days and what role Super 8mm played in them? How did the festival relate to Berlin’s (experimental) film scene of the time?

Guy Parker: Although many of the films in the program include experimentation, I would tend to describe them as alternative rather than experimental. Alternative in that they were produced, exhibited and distributed outside of existing systems and frameworks—to which they assume a critical, oppositional stance. Super 8 film had been a huge phenomena in Germany in the preceding years, with many millions of cameras and projectors sold. In the early 80s it offered alternative and independent filmmakers total production autonomy in an affordable way, not least because the market was saturated with cheap used gear as mainstream popularity of the format was falling away. Super 8 remained at the core of Interfilm right up until 1989, when submissions were finally accepted in other formats, including video.

It’s no secret that Berlin was, at the time, a magnet for people in search of alternatives and I think these films are a rich part of that culture, that history. Interfilm was Berlin’s first international Super 8 film festival and grew out of a loose connection of Berlin filmmakers who had been active in the alternative scene for some time.

Yana Yo: ‘Normalzustand,’ Germany, 1981

MA: The 1980s mark a strong decline in the importance for Super 8, as it gradually gets replaced by camcorders. Manufacturers discontinue its production of cameras of this format by the middle of the decade. The films gathered in ‘Alle Macht’ were made precisely during this moment when Super 8 was on its way out. Are technological changes reflected in the films you have selected? If so, how? And what drove artists and directors to stick to the medium despite its (imminent) obsolescence?

GP: I think it’s best viewed within context. In the 1960s, Super 8 had been marketed as a classic post-war consumer item or even something like a hyper-consumer item, in that it was not only a desirable device, its suggested use was to document and reinforce other aspects of consumer culture. Buy a camera, film your vacation, car, home, etc. Show the film off to friends, neighbours, repeat, repeat and so on.

Its limitations were overshadowed by its ease of use and affordability. Later on, many Super 8 camera manufacturers shifted towards evermore complex products until, by the late 1970s, Super 8 had apparently morphed into a highly sophisticated format aimed at only the most serious enthusiast—often slightly older, patriarchal figures—although its technical limitations remained essentially the same.

A reaction to and a negation of all of the above fed into the irreverence, sense of fun and opposition that runs through these films. They rejected the conservative mainstream consumer culture of the first wave and the aspirations to technical mastery of the second. They embraced the limitations of the format and a non-illusory mode of filmmaking, taking a media format deeply charged with ideology and turning it on its head.

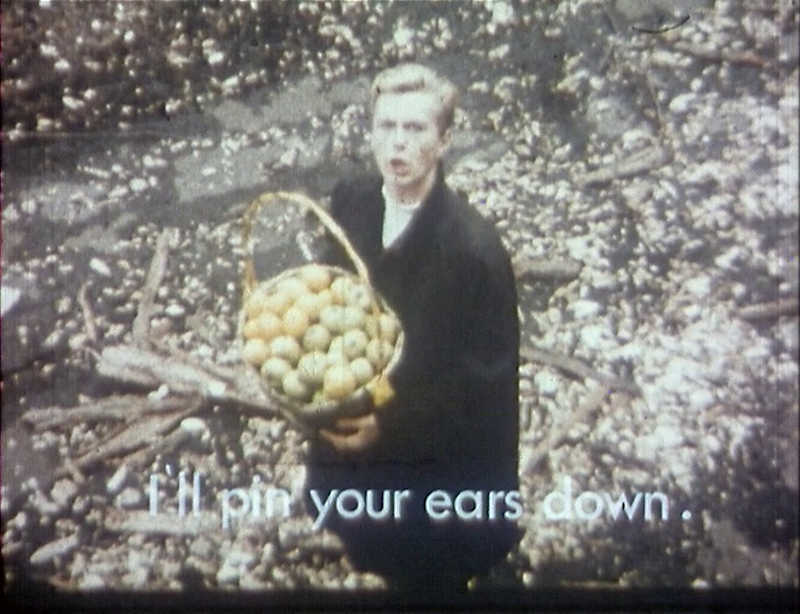

Uli Versum: ‘Zitrusfrüchte II/ Citrus Fruit II,’ Germany, 1985

MA: A lot of the films show life in the city or develop narratives only to then take them apart with a great deal of humour. What other shared concerns and techniques do you detect in your selection?

GP: There is a fever pitch of momentum and individualism in these films—the kind of energy that occurs when a movement breaks away from norms and invents its own way of doings things. An uncompromising commitment to autonomy and DIY culture at all costs is present throughout.

I like to think of it as comparable to the first wave of Punk music, when, against a background of late 70s Supergroups and Prog-Rock pretension, new bands appropriated the then largely abandoned fast three-minute rock ‘n’ roll track and made it their own: behold, Punk Rock. Similarly here, the fact that the format was being aimed at the cultural trash can meant these filmmakers felt free to effectively redefine its position in media practice.

Representations of nightlife and various aspects of an active counter culture reoccur throughout. Traditionally, anthropologist documentary filmmakers have adopted new compact formats, enabling them to get up close to their subjects with minimal disruption and I think here, the unobtrusiveness of Super 8 made it ideal to penetrate and film the many subcultures active in 1980s Berlin. Something like the 24-hour city, for instance, may seem unremarkable today but for the young people moving to West Berlin from one of Germany’s sleepy provincial towns, it must have been thrilling. I detect a strong desire to capture impressions, such as Berlin after dark, in the films, to share insights into undercurrents and subcultures that would otherwise remain hidden. Films such as ‘Geile Tiere im Dschungel’ (Knut Hoffmeister, 1980) and ‘Alaska’ (Oswald Berends, 1982), for example, creatively document moments in ways that would not have been possible without Super 8.

MA: What makes these experiments from 40 years ago worth watching today? Any lessons to learn for contemporary filmmakers or other artists working in an experimental vein?

GP: These films have a lack of preciousness, a sense of open access that seems to invite participation. They, like much of the work featured at Interfilm, seem to encourage the viewer to just pick up a camera and shoot. So although the festival has expanded and changed, I think they represent Interfilm’s present as well as its past.

For some young people, the otherliness of small gauge film technology, the aesthetics and raw power that exude from these films, will be a tonic. Others will find aspects of it curiously familiar, as many tropes and affects have, over the decades, been appropriated, recuperated and remediated by all forms of mainstream media (though rarely improved on).

As for lessons: I think they scream out “ignore anyone trying to teach you a lesson and do your own thing!” Make films for your yourself, your friends and the friends you’ll make in the process, and other people will want to see them. I think that’s what these filmmakers did and their work is still fresh today.

The current culture of alternative film, artists’ film, experimental film and video has become incredibly serious and mannered, probably not least because of the drift away from collectives and alternative spaces towards relocation in galleries, etc. The economy and autonomy of the production and exhibition of the short films featured in ‘Alle Macht der Super 8’ prove the potential of cutting out the influence of agents, algorithms, critics and even curators (!)

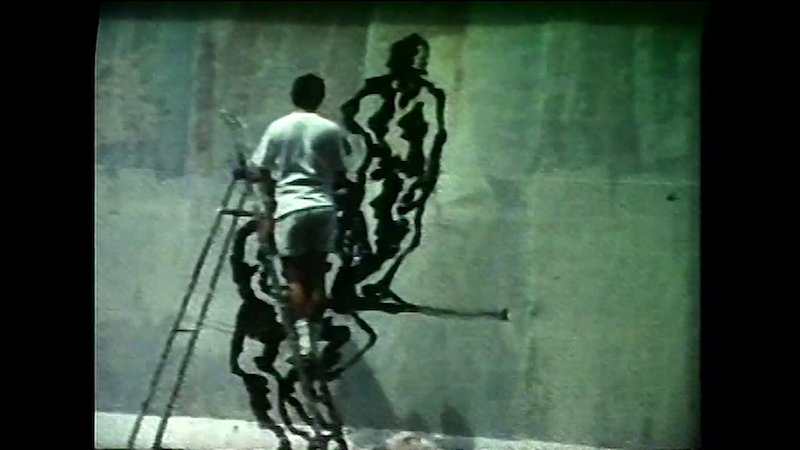

Raymond Red: ‘Pinoys in Berlin 1988,’ Philippines, 1988

MA: With its curation, Interfilm explicitly involves itself in current debates on post-colonialism, queer identities and participatory democracy, among other things. Are there any concerns the shorts from the 80s share with films from the competition or other specials in this 40th edition?

GP: Interfilm has somehow managed to retain a spirit of open access, a non-hierarchical approach to film, 40 years since its beginning, perhaps by judging the work rather than the artists’ CVs and always seeking to offer a platform to the underrepresented. They also understand the power of keeping things fun! I think this runs throughout the entire festival and is clearly a part of this program.

The films in this program were produced in a climate of political engagement and no small amount of disillusionment. The issues you mention are present here, included at a time when mainstream media would have largely denied access to them. For me, a concern that drove the makers of these films, one that remains extremely pertinent today, is the questioning of the actual media technology we use to express ourselves, especially when voicing left-field, counter cultural issues. The media giants that host, promote and profit from online video today are as laced with ideology, norms and agendas, as the manufacturers of Super 8 camera were to the passive consumerist, nuclear families of the 1960s.

There is an underlying awareness of the wider world of moving images present in this program that sometimes reveals itself as self determined resistance towards dominant culture, elsewhere as near paranoia about how those images are constructed and controlled. By making the compromise of using a lo-fi, near obsolete format, the filmmakers could shoot, edit and screen while retaining control of their work and possibly having more fun in the process. I find that very much in the spirit of Interfilm and worthy of note for us all.

Festival Info

Interfilm

40th International Short Film Festival Berlin

Festival: Nov. 5–10, 2024

interfilm.de

Various Venues