by Adela Lovric // Nov. 5, 2024

Andrea Fraser has been a singular force in contemporary art over the past four decades. Her work as both an artist and writer has come to define the field of institutional critique, taking a hard look at the art world’s flawed mechanisms of production and power through Bourdieusian and psychoanalytic lenses. Since the 1980s, she has probed the social, financial and affective economies of cultural organizations, fields, groups and individuals, employing a wide range of media and a rigorously researched approach.

We caught up with Fraser to discuss her ongoing exhibition at the Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation in Bolzano—the first survey dedicated to her works focused on the theme of collecting. Curated by Andrea Viliani with Vittoria Pavesi, the show spans work from the late 1980s through to recent pieces. The titular phrase—”I just don’t like eggs!”—is drawn from the script of Fraser’s seminal 1991 performance ‘May I Help You?,’ featured in the exhibition through four video iterations. In this piece, Fraser—or an actor—delivers a bitingly satirical monologue that shifts through different social roles within the art world, pointing at how cultural consumption relates to class. In a characteristically wry manner, the line “I just don’t like eggs!” sets the stage for a layered exploration of the deeper motivations underlying collecting, which extend well beyond simple enactments of taste. As Fraser warns me, “[t]here’s a range in the field of collecting just as there’s a range in the field of art making,” adding aesthetic disposition—as theorized by Pierre Bourdieu—as a dimension distinct from taste. Over the past 20 years, her interest has moved from considerations of the former to collecting in terms of the economics and politics of the art market.

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections,’ installation view, The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, Bolzano // Photo by Jürgen Eheim

Adela Lovric: Why did you decide to structure this exhibition around the theme of collecting?

Andrea Fraser: The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation is a foundation created by a private collector, and works from his collection are always on view on the second floor in temporary exhibitions curated by Eva Brioschi. And he also lives right above this foundation. So there’s a close proximity between the domestic context and the private collection on public display. I did a number of works in the 1990s about very similar situations, about collectors and collections and the relationship between art or cultural objects as they exist in the domestic context and how they exist in public art institutions, and what happens as they move from one context to the other. I felt that if I show these older works, it would structure for the viewers a critical reflection on the situation that they’re in, even if the work is not specifically about the Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, or about his collection.

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections,’ installation view, The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, Bolzano // Photo by Luca Meneghel

AL: Could you give an example of an artwork that particularly draws attention to the context of the exhibition site?

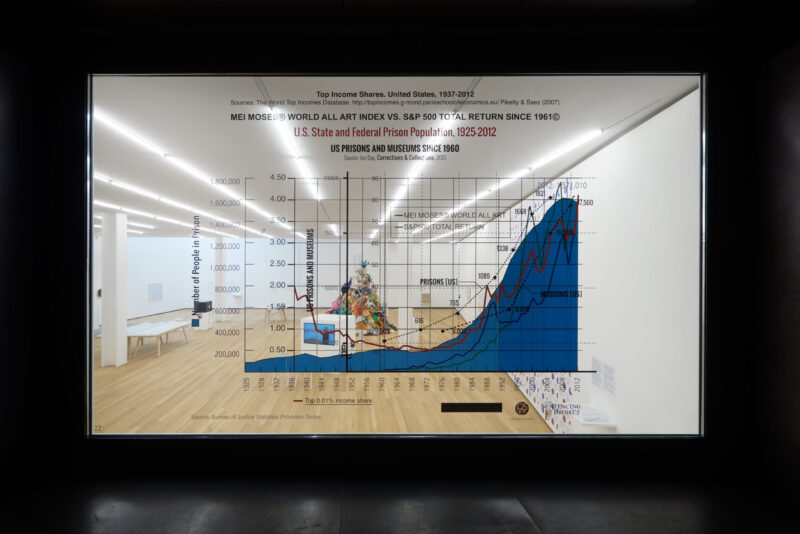

AF: There is one piece [‘CCI Tehachapi Kings Road’] that I created in 2014 in California, where I went into a maximum security prison, recorded audio in a cell block and transferred it to a museum in Los Angeles. At the Dalle Nogare Foundation, this audio is installed in the courtyard you pass through as you enter the venue. I thought it might be a stretch, because it’s in English and there isn’t a situation of mass incarceration in Italy, as far as I know. But I think that it really does function quite effectively. What it pulls out and activates is the contradiction of this beautiful outdoor space with the vineyards and a stream running down the hillside that is open to the public during particular hours, and the fact that it is also a high security space. There are two levels of gates that are closed and locked when the foundation is closed, there are security cameras all around, there are really heavy metal doors and gates that close down around the window. All of that is part of the structure of that space, which is camouflaged by the beauty of the environment, that gets activated by the piece. So that might be one of the ways the work triggers a critical reflection on the context, which is what my goal is as an artist.

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections,’ installation view, The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, Bolzano // Photo by Jürgen Eheim

AL: During the tour of the exhibition, you mentioned that your 1992 work ‘Aren’t They Lovely’ is one of the most radical things you were able to do in a museum. Could you explain how it challenged your own ideas about art and collecting?

AF: It’s a project that I did at the University Art Museum, now the Berkeley Art Museum, affiliated with the University of California, Berkeley. I was invited to take up the role of a curator and make an exhibition with the collection of the museum. I found one bequest to the museum by a woman who graduated from the university in 1916 and died in 1978, leaving everything she had to the university. The exhibition showed material from the museum archives documenting the whole background of the bequest: her first outreach to the university, her efforts to negotiate some kind of support in exchange for the collection, and the response of people from university and then the museum. When I went into that project, I assumed that patrons, collectors and donors always had the power in these situations in relation to museums. What I found in this case was the opposite. This was a woman who had a significant art collection, but she had no money. She didn’t want to sell the collection, because it was part of her life, she was devoted to it. She was trying to negotiate with the university for some kind of support. They strung her along for a decade, and then she died in an unheated apartment, basically, at a fairly young age. She was an incredible woman with an extraordinary life, and at the end of her life, she was reduced to this stuff that she’d accumulated by the university that is celebrating her, but they’re really just exploiting her. It wasn’t just the university, it was also the museum that had just been created. That was not at all what I expected to find.

It helped me step back from my own disposition, which is the disposition of most artists and art professionals, to consider their relationship to art and culture as the most legitimate one. That sense of legitimacy is often also the basis for the critique or rejection of the relationship to culture that other people have, including collectors and donors to museums. Pierre Bourdieu talks about this: he distinguishes between what he calls a domestic relationship to culture—people who grow up with art or collect art, who have art in their homes—and what he calls a pedantic relationship to culture—people who encounter art through an educational system, become professionalized within the field, and who then tend to privilege their own symbolic consumption of culture over the material consumption of owning and living with art. And that certainly had been the position from which I was working, and the basis of a politics that I brought to thinking about museums and cultural institutions in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections,’ installation view, The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, Bolzano // Photo by Jürgen Eheim

AL: Could you speak about institutional critique in your recent practice and in specific works at the Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation?

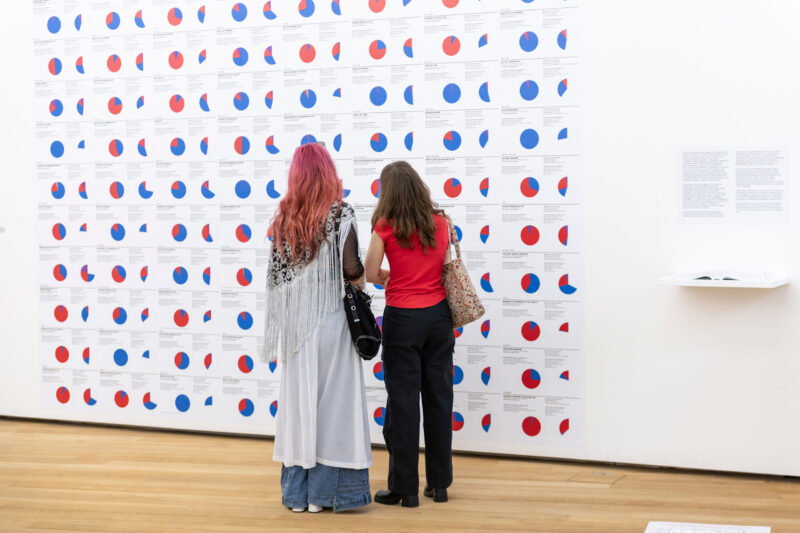

AF: My work has changed a lot since the 1990s and especially in the last 15 years, but it always has swung between extremes of social and economic investigations on one side and a focus on psychology, affective experience and subjectivity on the other. A lot of my work of the last 15 years hasn’t been site-specific at all in the way that the work in the show is. With a few exceptions, and those are in the show: the audio installations that I did in 2014 and 2016 about the parallels between mass incarceration in the United States and prison building and museum building, and how museums and prisons represent the extremes of an increasingly polarized society in the United States; and ‘2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics,’ which documents the political contributions of the trustees of 128 art museums in the U.S. during the 2016 election cycle, in which Trump was elected. Those two sets of projects focus on the museum and are consistent with my previous work. But my most recent work, and a lot of the work that I’ve done in the last 15 years, is not specifically related to art institutions and has taken the form of performance. I’m in a different place than I was when I did a lot of the work in the show in Bolzano, and also when I did a lot of the writing that still circulates and has contributed to the way people think about institutional critique and the art market.

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections,’ installation view, The Antonio Dalle Nogare Foundation, Bolzano // Photo by Luca Meneghel

AL: Where would you say institutional critique is located now?

AF: It takes a lot of different forms. There are people who are very actively and effectively challenging museums and other kinds of institutions. I think, of course, of Nan Goldin and P.A.I.N., and of activism around patronage and trusteeship in the U.S. and the U.K., and to some extent in Germany in terms of the Nazi backgrounds of some collectors and patrons. That’s institutional critique as a form of cultural activism that’s not necessarily manifesting as artworks that people are putting in museums, but in activism around museums. I see it as museum reform, but then there’s a question of what the nature of that reform is. One form of this activism is what I call the politics of the toxic trustee or the toxic patron, which is often very focused on specific people, individuals or sources of money that go into the art world. The challenge is that those politics can imply that if we just get rid of those people or that money, then it’s all fine, which I don’t believe is the case.

Then there’s the question of institutional critique as an art practice which, for me, is not just art about the art world, or art that’s critical of museums. I’ve defined institutional critique as a practice of critically-reflexive site specificity. What’s really important to me is that there is critical reflexivity. That’s where I distinguish institutional critique from, say, political art or cultural activism, which is not necessarily reflexive. I would say that in the art world and elsewhere, politics and political position-taking usually identifies what’s wrong as over there somewhere, in what other people are doing, and involves attacking that person or that structure. That’s important and called for in many cases. Institutional critique, for me, is not doing that but instead engaging in reflexive critique; it’s more nuanced, and it’s also why sometimes I describe it not as a political practice, but as an ethical practice.

Exhibition Info

Fondazione Antonio Dalle Nogare

‘«I just don’t like eggs!»: Andrea Fraser on collectors, collecting, collections’

Exhibition: Apr. 13, 2024-Feb. 22, 2025

fondazioneantoniodallenogare.com

Via Rafenstein 19, 39100 Bolzano, Italy, click here for map