by Noushin Afzali // Nov. 29, 2024

Ali Eyal is a multidisciplinary artist whose works delve deep into themes of memory, displacement and trauma, often rooted in his experiences growing up in war-torn Iraq. Known for his powerful storytelling, Eyal navigates the intersections of personal and collective histories, crafting narratives that blend fiction with reality to reclaim a sense of lost homeland and identity. Through mediums ranging from painting and drawing to performance and video, he constructs layered, immersive works that invite audiences to reflect on the complexities of violence, loss and reconciliation.

In what follows, we discuss the formative role of storytelling in Eyal’s life and art, tracing it back to childhood tales spun during moments of familial intimacy. These early experiences, set against the backdrop of Iraq’s tumultuous political landscape, have profoundly influenced his narrative approach, allowing him to transform personal memories into universal reflections on war, exile and survival. He shares insights into his creative process, where imagination serves as a tool for reconstructing fragmented realities and exploring the unseen impacts of conflict.

Ali Eyal: ‘Paper, pen, map in a pocket and,’ 2023, oil and conté on canvas, 213 x 335 cm, Brief Histories, NYC // Photo by Isak Berbic

Noushin Afzali: Could you share more about how you approach storytelling within your practice, and how your experiences growing up in Iraq have influenced your narrative style?

Ali Eyal: At the heart of my practice is a deep engagement with imagination and storytelling, often addressing the hardships of war and occupation. Growing up near Babylon (modern day Al-Hillah) profoundly shaped my perspective, and I frequently set my work in an imagined version of the Iraqi village from which my family was ethnically cleansed. Through fiction, I reclaim a lost homeland and confront the trauma of mass death and exile. Storytelling is deeply rooted in Iraqi culture, and I tap into that richness to explore themes of violence, displacement and the potential for reconciliation.

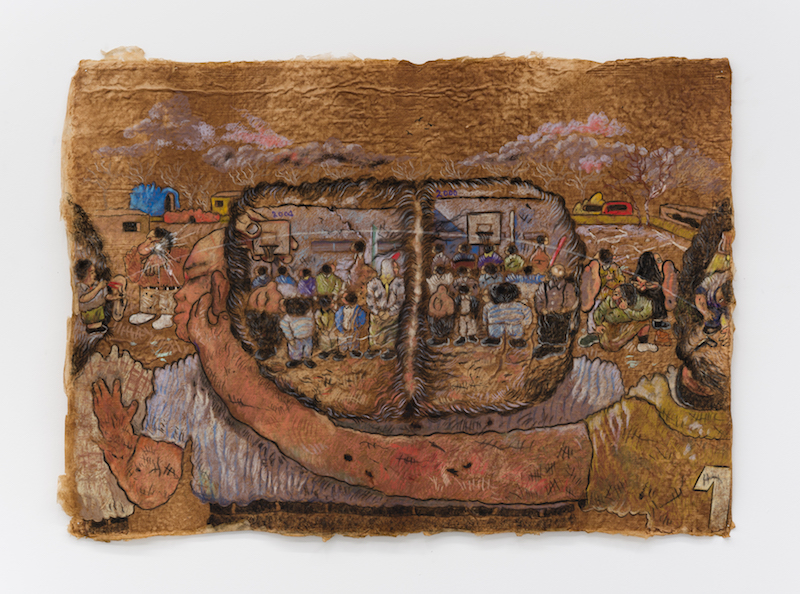

Ali Eyal: ‘My mom surprised me to show me a 2000 calendar, but what did I show my mom?,’ pastel on BHU-09 Bhutan Rural Tsharsho, 30 x 22 in // All images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Ehrlich Steinberg, Los Angeles

NA: Was literature or storytelling important to you growing up, or did that interest develop later?

AE: It began in childhood with my mother. At bedtime, I would run my fingers through her hair, creating stories, imagining objects like a new car or a talking phone as central characters. In the 1990s, buying something new was rare, so these items became part of my epic tales.

NA: It sounds like the roles were reversed—you were the storyteller for your mother.

AE: Exactly. And after I immigrated to Europe in January 2020, COVID-19 intensified the isolation I felt as a new immigrant. That period of solitude brought me back to those childhood memories—moments when my imagination could turn everyday things into grand narratives. I revisited those stories, the feeling of heads floating like planets above me, and used that introspection to inform my recent work.

Ali Eyal: ‘Three heads walking between towns, and,’ 2022, oil on canvas, conté stick, Band-Aid, 65 x 109 inches, Brief Histories, NYC // Photo by Isak Berbic

NA: Themes of displacement and loss recur across your work, especially given your background and Iraq’s political context. How do you convey these intense experiences, and what do you hope viewers take away?

AE: My process often feels guided by something beyond my control. It can start with a simple sketch—like empty heads—and colors that emerge between brushstrokes. Born in 1994, I experienced the initial invasion, and its aftermath shaped my life. My family’s farm near the “Triangle of Death” was destroyed in 2006, and several uncles were kidnapped or killed. My father is still missing. This constant presence of loss manifests in my work through fictional or half-portraits, often depicting the backs of heads.

Recently, one surviving uncle returned. When I asked to paint his portrait, he turned and showed me the back of his head. That moment was more powerful than any frontal image I could create.

NA: So, the trauma you depict isn’t only about the U.S. invasion but also the civil war that followed?

AE: Exactly. The invasion brought chaos. I remember coalition forces bombing a telecommunications center near our village at 2am—the house shook, and I woke up screaming. Suddenly, everything changed: our president was American, parents were paid in dollars and kids received bags with American flags. A phone line center next to my elementary school was bombed. I still remember our class photo taken afterward. The wall behind us had developed a huge crack, swallowing all the political drawings I had made as a child. That crack became a metaphor for everything that was happening around us.

Ali Eyal: ‘Just a group school photo, but..,’ 21 x 30 inches, pastel on Japanese paper // All images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Sara’s, New York

NA: Storytelling seems essential for processing these memories.

AE: Yes, it’s a way to reimagine reality. My recent work combines text and painting, with my brush metaphorically connected to speakers producing aesthetic sounds. Each project feels like reconstructing fragments from an Iraqi cultural manual, hoping to replace the corruption that has fed the land with something restorative.

I want viewers to experience horrific events indirectly, not through explicit violence. My 25 years in Iraq were marked by distant bombings, interrupting daily life and causing constant fear. I hope to convey that complexity, inspiring confusion and reflection—because sometimes, understanding begins with confusion.

Ali Eyal & David Horvitz: ‘California / كالفورنيا,’ digital photos printed on Luster paper, diptych; Installation views of ‘A new garden from old wounds,’ ChertLüdde / Potsdamer Strasse, Berlin, 2024

NA: Your recent exhibition, ‘A new garden from old wounds’ at ChertLüdde in Berlin, involved collaboration with David Horvitz. What was this experience like for you?

AE: David is incredibly open and social. We connected during a project for Frieze LA, where we drove around, doing simple, playful things—like writing “California” in the sand, him in English and me in Arabic, and watching the waves erase it. This impermanence was powerful.

NA: Did collaborating with David change your usual solo practice?

AE: Yes. David’s peaceful, flexible approach contrasted with my intense process, teaching me valuable lessons. His community-building in LA gave me a new perspective on the city and the importance of connection.

NA: You work across various media. What guides your choice for each project?

AE: The medium chooses me. I listen to the idea, much like listening to a parent or partner, and see which form fits best. It’s that intuitive for me.

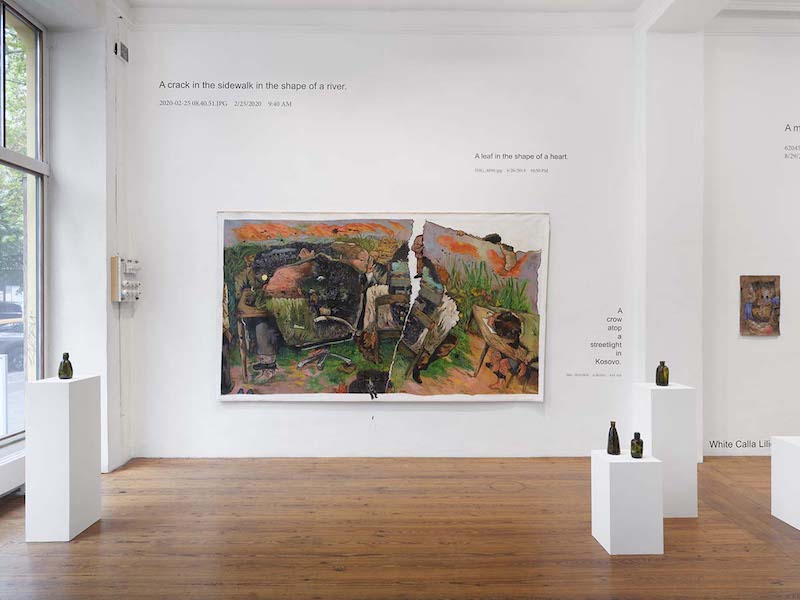

Ali Eyal & David Horvitz: ‘A new garden from old wounds,’ installation view at ChertLüdde / Potsdamer Strasse, Berlin, 2024

NA: Your work has been showcased in major exhibitions like Documenta 15 and the 58th Carnegie International. How have these platforms influenced your visibility, and how do global spaces shape conversations around your themes?

AE: Documenta was a disappointing experience. Despite its prestige, it felt heavily policed—like a checkpoint. Conversely, the Carnegie International was a positive experience, giving me valuable exposure.

However, a residency in Beirut (Ashkal Alwan) impacted me more than any exhibition. It provided an intense, theoretical environment where I critically reassessed my work, renewing my approach to painting and drawing.

NA: So, prestige isn’t the main drive for you?

AE: No. Many artists seek visibility from international venues, but for me, the environment and space for reflection matter more. Documenta felt restrictive, especially in terms of freedom of speech—a growing issue in Germany. Residencies, on the other hand, have been transformative. They offered time for introspection, especially during the pandemic, which opened a new chapter in my practice.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Visible Records

Ali Eyal: ‘Leaving My Eyelids Behind’

Exhibition: Nov. 8-Dec. 13, 2024

visible-records.com

1740 Broadway St, Charlottesville, VA 22902, USA, click here for map