by William Kherbek // Mar. 14, 2025

This article is part of our feature topic Public.

Samra Mayanja is a performance artist, poet and curator responsible for the project space The Call Centre in Hackney Wick, London. Mayanja’s performances, often based on a character she has developed named Holiday, are searingly emotional, eye-wateringly hilarious and overwhelmingly generous. These theatrical works are also robustly participatory, both engaging and—to use Mayanja’s preferred term—”implicating” audiences in the narratives of the pieces. The boundaries between the public and the private, hopelessly blurred by social media, feature as a key component of Mayanja’s bodies of work. The audience is never either fully outside or inside her narratives. We spoke about the ways in which Mayanja uses form, language, voice and embodiment as vectors of creation in her works, and how curating a space can create new forms of relation between audiences and publics.

Photo by Laura Fiorio

William Kherbek: Your performances often involve you alone on stage before an audience. Could you speak about how you approach the numerical imbalance of performing solo in somewhat participatory works, in front of sometimes very large audiences?

Samra Mayanja: When I was at school, we did a term in public speaking, and we’d study speeches and study the voice and how poetry can be spoken, and I started taking that quite seriously, and at some point I was in public speaking competitions. In that context, sometimes I’d perform and the room would be huge but there’d be three people and lots of empty seats. There would be so much air and you’d have to try to fill it. There was no music, nothing. Just you. And then I’d perform. I think I have a strong sense of how difficult it is to fill a room with just a voice, but also the possibilities there are to connect with people because there’s nothing there.

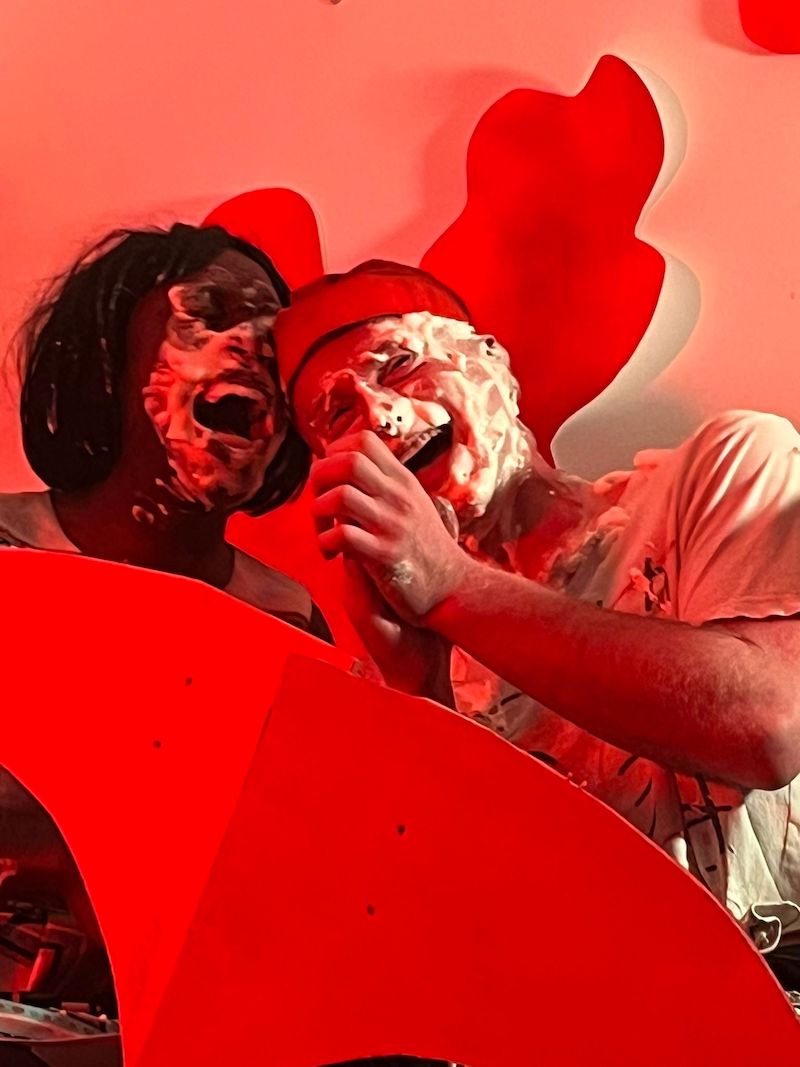

Photos by different audience members at THE CALL CENTRE

WK: Speaking about voice, in that many of your performances involve the character exposing intimate and highly personal details, I wanted to ask how you cultivate your “public” version of the “private” voice?

SM: My dad passed away in August of 2021. In November of 2021, I was invited to read at a poetry night, and I had been thinking about performance and how “performance” is only performed in a performance art context that, to me, has limits. I wanted to move through that. With my quite varied training between performing on stage in music groups, drumming, public speaking, reading poetry, speaking poetry, doing so many things performatively, I’ve been in lots of contexts and audiences are different. They have different conventions in terms of their reactions. You might be the same person with the same psychology, but in a stand up comedy setting vs. a poetry setting, you’d respond differently to the same material. I was just like “OK, fuck it. I’m going to bring something that is definitely not prepared poetry to this space. What do I have?” At that point, I’d been developing this character, Holiday, who was basically an outlet. I was living in a quite toxic anarchist eco-commune and I wanted to create a character who had no radical politics and was just a blasé art hun, the sort of person who would walk into a room and be like “it fucking stinks in here!”

So I wanted to challenge the context or learn about the bounds of the audience and how forms work in different spaces, and at that point I was also battling with the loss of my dad, who, from age zero to five, was super-present, a wonderful and amazing person, then from five to 18, was absent. At 18, we became friends and it was amazing. And then when I was 24, he passed away. All I could think was “that’s the funniest thing that’s ever happened to me, because, you don’t get to die now! You’ve got to stay, because we’re mates now!” Then I thought about how Holiday would react to this. Holiday, who’s kind of ridiculous. Holiday would say I still need that, so I’m going to start auditioning actors to play my dad in this ongoing audition called life. I still need someone. I’m petulant, bratty, entitled—things that I have within me but don’t necessarily reveal or they don’t necessarily lurch out, they’re kind of repressed. I wrote a stream-of-consciousness script that had these absurd voices auditioning the dad.

Holiday, being this kind of public voice, is not me, it’s a character, but it’s almost like creating a tunnel or a process through which I’ll be changed, if only momentarily, on stage. The self-conscious process of imagining and auditioning actors to play my dad in this ongoing performance—writing and performing it—means that now I’m at the stage where I am actually auditioning people and I’m changed by that.

Photos by different audience members at THE CALL CENTRE

WK: How do you negotiate the layers of revelation the performance requires? In that we live in an age of oversharing—digital culture practically requires it—and there are expectations of intimacy in a one-person stage show, is there a sense of moving between different forms of revealing and concealing for you?

SM: I’ve been thinking a lot about shyness. Actually, I’m quite a shy person in the sense that I often don’t know in day-to-day speech what to reveal and what not to reveal. That feels quite complicated to me and I guess that’s informed my interest in speech, what’s legible and what’s illegible. Sometimes, it’s the illegibility of my own body that I’m struggling with. I’m feeling something and I don’t understand how to say it and that then drives this obsession with language and trying to find the words to speak, because it’s actually a struggle with something.

I understand that there’s a culture of oversharing but actually, for me, the intimate is not a space to overshare. I don’t think Holiday is oversharing, in that traditional kind of one-woman-show way. I think what Holiday is doing is using different voices, all of which I am actually speaking. One is the Lioness Empress, a chain-smoking cat that is like the executive function in the brain. Another one is the Sixth Sense, which is proprioceptive and guides orientation and comes out of a Dickensian music hall kind of thing. Then there’s the Tarot Reader, who is sensuous and bodily and is a kind of a combination of Nigella Lawson and Sandra Bernhardt and Grace Jones, or something. They are all revealing layers of the character’s psyche, but they’re not necessarily saying “this is exactly what happened.” Rather, in the texture of the voice, all of those things are revealed. It’s about peeling back layers of the mind and moving between different sides of the curtain.

Photo by Laura Fiorio

WK: In moving between these “sides of the curtain” are there ways in which you think about the “internal public” of these characters? Are they layers, for example, of some kind of Id-Ego-SuperEgo form?

SM: I’ve had different entry points. One project I worked on was called ‘Scream’ and it was influenced by a lot of things, one of which was a film called ‘Sambizanga’ by Sarah Maldoror. In that film, the central character is called Maria and she’s in colonial Angola and her husband is taken by Portuguese colonial forces. The rest of the film is her walking for miles and miles with this baby on her back, going to police stations and asking “where is my husband?” She sings, in such a way that it’s heartbreaking. And it felt to me that she was trying to sing over a wall or over a building, but that the voice was not only hers; she was carrying a lot of voices within her. All the voices come through her, the texture [of her singing], and by the end, she’s just screaming. I think about it more like that.

The process I use is either a kind of automatic writing process, or I sit with a recorder and I improvise, sing or do vocalisations. There’s something of the voices that you have within you that you don’t know, that you’re not aware of—the voices that speak through you. Improvisation that taps into the subconscious, but it’s also a mode of communication. With what, I’m not so sure, but there are so many things that are revealed to me, so many architectures that are being made, when I just sing by myself or improvise sounds and I can’t pinpoint where I’ve heard them, but they give me some kind of insight into a character, or a place, or conflict. That’s where my approach comes from: the screaming character who is screaming not just for themselves but because they want to reach someone else, or because someone has been wrenched away from them, or because there’s some distance, some longing, love or desire.

Photos by different audience members at THE CALL CENTRE

WK: How much would you say running a project space has influenced the work and your approach to creating the character and performances?

SM: Massively. I started it because I was just sick of rejections. I have some sense of the percentage of rejections I get in a year and I feel like they went up in 2022. I asked myself what I was actually applying to do. And I answered that I’m applying to have a space to try things.

The space I actually perform in is the testing ground, and that was something I didn’t have. I decided I was going to set this up, but how was I going to frame it? The thing I’m most interested in is the voice and the unspeakable and there are lots of artists who I’ve written reams and reams of research about and read about, and they’re my friends. But what would it be like to work alongside them in this space?

I’d invite someone to do a 30-minute performance and then we’d do this “silly-but-serious” Q&A. The thing behind the silly-serious Q&A is that it has really well-researched questions, because these are artists I’ve followed for years and I know their work, but it also had games and [through them] the artists were released to their practice. The games are almost like a palate cleanser between questions, that resets everyone and then we get back into the serious thing. It breaks the form of the artist’s Q&A, which feels absurd. Most of the people in the room don’t know each other, or don’t know everyone in the room, but [the format] is so intimate that you can really connect with each other.