by Jeffrey Grunthaner // Mar. 21, 2025

‘Aber hier leben? Nein danke. Surrealismus + Antifaschismus’ at Munich’s Lenbachhaus is a historically illuminating exhibition, which carries a great deal of suggestiveness for our contemporary moment. Across a sprawling selection of artworks—ranging from paintings and films to poetry chapbooks and even more vestigial ephemera—the group exhibition highlights the politicized aspects of the surrealist project. These too often overlooked political impulses not only placed the artists involved with surrealism at odds with the bourgeoisie of the interwar period, but with fascism, Falangism in Spain and colonialism more generally. Delving into the socio-political context and activism of several of surrealism’s key protagonists—not just of the European stamp, and not just the men associated with the movement—‘Aber hier leben? Nein danke’ also makes a more subtle point about surrealist methodologies being inherently anti-fascist at their core.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Diego Rivera, Leon Trotsky and André Breton, 1938 // © Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, S.C

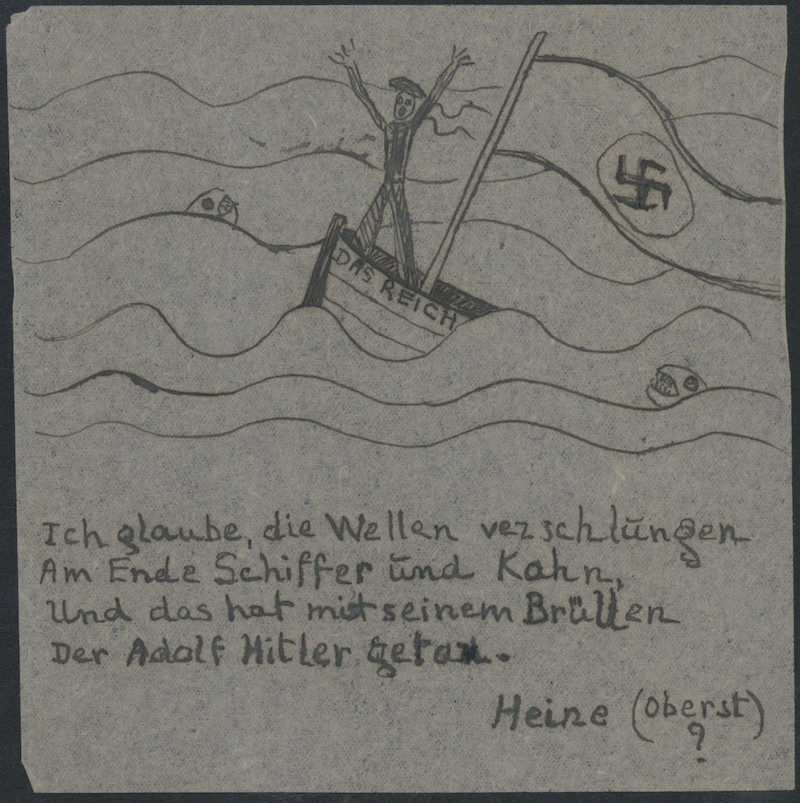

Many of the works on view, following surrealism’s task to “changer la vie” in the name of desire and dreams, document the extent to which surrealist artists were embroiled in direct action resistance during a time of widespread Nazi occupation. Claude Cahun and their partner, Marcel Moore, for example, strategically placed agitprop ephemera around the Channel Island of Jersey (where the two of them resided), intending thereby to make German soldiers think things were going very badly for them at that stage of the war. Meanwhile, in occupied France, intermedia works by the collective La Main à plume would foreground poetry in the grand sense: not merely as a linguistic complex, but as a series of publishing actions intended to demoralize fascism’s militaristic thesis.

Claude Cahun (Lucie Schwob) + Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe): ‘Untitled (Propaganda leaflet),’ 1940-1945 // Jersey Heritage

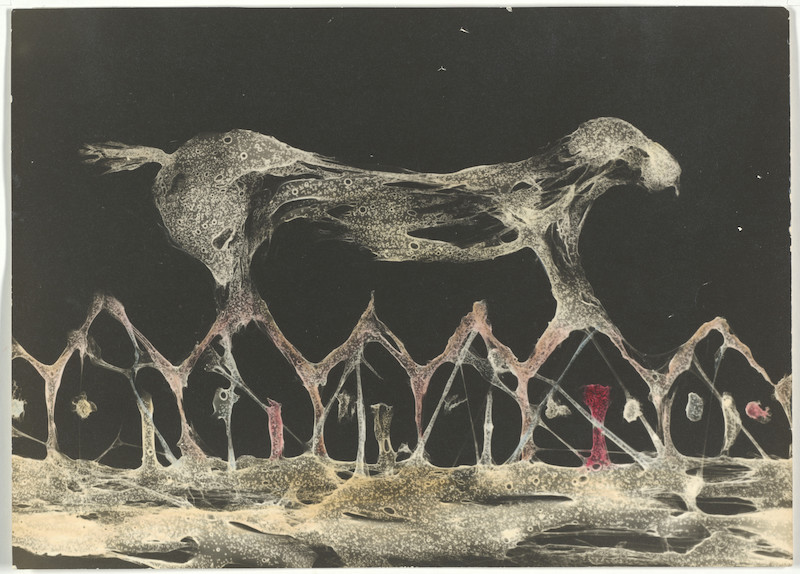

Additional standouts include works by Jindřich Heisler, whose series ‘De la même farine’ (1944) was created under extreme duress when the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia. At first, Heisler’s darkly lucid, almost otherworldly images might not seem overtly political. But in their very facture—their unsettled surfaces, the visionary spaces they evoke, the grotesque figures portrayed—his contributions are living artifacts of surrealism’s potential to resist fascistic coercion through a sort of theurgic adaptation. Heisler’s works not only document his disquieting state of mind (he was confined to hiding from Nazi soldiers for most of the war), but exemplify surrealist art as an act of transgression.

Jindřich Heisler: ‘Untitled,’ from the series ‘De la même farine’ (From the same flour), 1944 // Private collection, Paris

History and place form an essential feature of the exhibition’s design; its layout revisits not only periods of surrealist-oriented activism during WWII, but moves through different countries and continents, showing surrealism’s influence on the Black Liberation Movement, and in anti-colonial uprising in places like Martinique and Algeria. Specific to this last, the mural-like painting ‘The Grand tableau antifasciste collectif’ (1960) is a cadavre exquis that bears witness to surrealism’s influence on occupied Algeria, where rejecting rationalism was tantamount to forming networks opposed to police control. But as the surrealist project reconfigured itself for different causes and in different countries across the 20th century, one might wonder if it always preserved the kernel of unreality that originally powered its transformative momentum. Or did surrealism’s perpetually antagonistic veneer ultimately reduce it to just another romantic ideology of opposition, more or less useful?

Ted Joans: ‘Outograph,’ 1993, found postcard, cutout and collage // Private collection, New York © Ted Joans Estate, courtesy of Laura Corsiglia and Zürcher Gallery

‘Aber hier leben? Nein danke’ is silent on this question, which is telling for surrealism’s continued relevance. Presenting surrealism as an avant-garde movement that exceeded strictly aesthetic limits, the curators convincingly establish that surrealist actions did, in fact, mobilize culture and ideology as weapons. However, the two most contemporary artists included—Ted Joans and China Miéville, a jazz-inspired poet and a novelist, respectively—seem more inspired by surrealism’s legacy than anything else. At base, while ‘Aber hier leben? Nein danke’ clearly shows how surrealism destabilized experiential frameworks that made colonial systems—particularly those in French-occupied Algeria—seem not only viable but inevitable, it’s still, as only befits a museum exhibition, focused on the past. While one can appreciate the adversarial quality of some works on view, too many have already slid into the facticity of art history: an atmosphere that doesn’t allow for the properly surrealist élan of counter-factuality to manifest in unpredictable, anarchic ways.

Exhibition Info

Lenbachhaus

Group Show: ‘Aber hier leben? Nein danke’

Exhibition: Oct. 15, 2024-Mar. 30, 2025

lenbachhaus.de

Luisenstraße 33, 80333 Munich, click here for map