Article by Katharine Doyle // Jul. 08, 2017

In ‘Haptic Field’—artist Chris Salter‘s collaboration with TeZ and Ian Hattwick—established language formed by sight is renounced and re-configured as a secondary sense. The installation invites participants to explore a surreal haptic environment in a complex work, where wearable technology meets bodily sensation. Haptic experience begins with the physical understanding of an environment through the body’s senses, which generates messages to the brain and generates our spatial awareness. The work is presented in Berliner Festspiele’s exhibition ‘Limits of knowing’ at Martin-Gropius-Bau as part of their ‘Immersion’ program, in which the content of selected artworks exists in the viewer’s experience instead of a finalised aesthetic product. Taking part in ‘Haptic Field,’ participants are returned to a state of childish oblivion, in which uncertainty is fused with unbounded curiosity about the space they occupy.

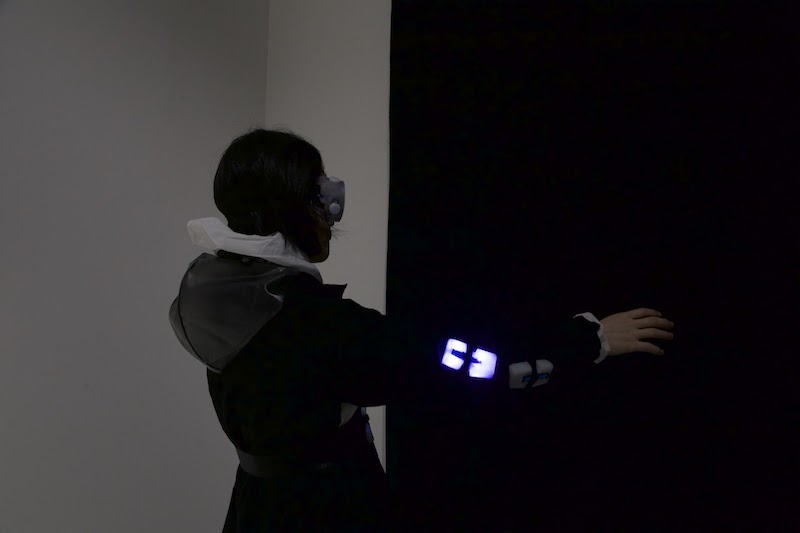

Chris Salter and TeZ, ‘Haptic Field,’ Installation view // Photo by Aina Wang

As suggested by its title, ‘Haptic Field’ interrogates our dependence on sight within a sensory environment. In doing so, it inevitably addresses the psychoanalytic effect of haptics. The work’s collapsing of inhibitions corresponds with French philosopher Jacques Lacan’s theory of the ‘mirror stage.’ Upon discovering their complete self within a mirror reflection, the human infant strives throughout their entire life to achieve the ideal ‘I.’ The point of ‘Haptic Field’ is to collapse our inhibitions, and its probing of this relationship between sight and self makes Lacan’s idea a useful tool for reading the piece.

The fact that ‘Haptic Field’ is a participatory project also imbues its treatment of sight with sociopolitical implications. According to Lacan, our sense of self is fundamentally dependent on establishment of the ‘other’ through adherence to social frameworks; this designation of otherness is ultimately upheld by our use of language formed through vision. Sight enables our interactivity with others, and allows us to conceive of our identity in relation to them. When considered in this light, ‘Haptic Field’ becomes even more conceptually complex than simply a surreal interactive experience. The feeling of immersion is generally considered to be an individual, subjective experience, but ‘Haptic Field’ explores the possibilities of multiple participants experiencing equal sensations at once: that which we think we experience individually becomes collective.

The experience of immersion begins even before fully entering the haptic environment. Participants are asked to put on suits, fitted with integrated sensors and vibrating actuators, before being handed clouded goggles and ushered through a dark-curtained entrance. The uniformity of this preparatory procedure feels like a ritualistic introduction, diminishing preconceptions of what might await inside. The relationship to contemporary fashion is important to the basis of the installation, as well. The costume element and the sleek décor of the changing area gives the work a stylized air, yet does so without jeopardizing a more powerful message on the social implications of clothing. When self-expression is so strongly based on how we present ourselves externally, clothing offers the potential to be brought closer to realising our super-ego. Yet in Salter’s world, the appearance of the clothes seems less significant than their physical connection to our bodies, their potential to act as an extension of ourselves.

Chris Salter and TeZ, ‘Haptic Field,’ Installation view // Photo by Aina Wang

Inside the immersive space, visitors must negotiate around three rooms equipped with hanging lights and an eerie soundscape. In the installation, your own sight is heavily reduced to a blurred vision, dissolving your spatial awareness in relation to other participants. Other visitors are only identifiable by the flashing lights attached to their bodies and the delicate rattling of the actuators attached to their jackets. Visually, their forms are condensed to shadowy entities, seemingly indifferent to your presence as they drift by. But this encountering of others is rare, as the piece is intended for a limited number of participants at a time. Periodically, the space plunges into darkness before returning to an ambient green or blue, and later it is filled with a more sinister red. At one stage, the room erupts into a stark white atmosphere, accompanied by the sensation of the actuators’ vigorous buzzing across the body. The yelps of others around the room reminds you that your experience is communally felt.

Salter’s transcendental creation feels like a hallucinogenic escape from the logic of reality, like a reversion to a time without comprehension. Within a tumultuous world constantly advocating that identity is definable by difference, this type of artwork is often regarded as a temporary sanctuary, bringing participants closer to a shared sensory experience. It throws up the question of what it may feel like if the boundary between subjective experience and collective experience were to be dissolved. The piece may seem utopian in this sense, but it is this utopianism that drives us to consider the reality we must return to.

Chris Salter and TeZ, ‘Haptic Field,’ Installation view // Photo by Aina Wang

The demolition of the self-consciousness of the super-ego in ‘Haptic Field’ may feel liberating for some visitors. On an experiential level, the technical features of the work make for an incredibly stimulating experience. Yet it is Salter’s ability to effectively merge the spectacle of new-media aesthetic with a form of socio-political experiment that makes the work so interesting. To call it utopian would diminish the multi-faceted nature of the work; not all of Salter’s implications are necessarily positive. For example, the uniformity in costume and blurring of sight essentially saps participants of their individual identity, which makes existence alongside others so dynamic and diverse. Chris Salter’s work does not provide a specific commentary, or any answers, but rather provides a lively space for these complicated questions to be explored.