This Spring, American artist and filmmaker Doug Aitken contributed his site-specific architectural intervention ‘Mirage’ to the group exhibition DesertX, which took place in California’s Coachella Valley. Exhibited projects by established and emerging artists amplified and articulated global and local issues—ranging from climate change to tribal culture to immigration—in this pristine desert setting.

We caught up with Aitken in L.A. to discuss his piece for the exhibition, as well as his wider artistic engagement with natural environments and processes, and the tradition of Land Art in which it is embedded.

Doug Aitken: ‘Mirage’ 2017, Desert X installation view // Photo by Doug Aitken Workshop, courtesy the artist and Desert X.

Berlin Art Link: ‘Mirage’ for the recent DesertX exhibition uses the architectural language of the Wild West to reflect nature back to visitors, as a critique of the idea of conquest and the fiction of uninhabited natural settings. How do you employ architecture as a tool in your works?

Doug Aitken: For me, the work ‘Mirage’ was a kind of gradual evolution of different projects, looking at the idea of reflectivity, the idea of bringing the viewer into the work and creating an encounter that was happening in real time that wasn’t necessarily authored. And I think that also comes back to the work itself as a structure. I thought a lot about the architecture that we don’t see and the experiences that we don’t record and I think, in a country like America, you find yourself constantly moving between point a and point b, but the space in between is often not really noted.

In ‘Mirage’, I wanted to take the form of suburban house, that type of repetitious typology, and I wanted to focus on it. Instead of making it dynamic and unique, I wanted to use the most mundane vessel for this project. So, we took this one story suburban home and I really wanted to drain the blood out of it. And to reduce it so that it no longer had a history, occupants, possessions, materialism, but only the form was left. Then, to take that form and kind of rework it, to pull it out of the kind of repetitious area that you’d find it in and isolate it. To make the work, I really needed a location with a view. I needed a place that wasn’t sublimely natural, but was instead in this twilight zone of development and raw nature. The location is this kind of boulder stream hillside in the desert. It’s very primal, but overlooks this valley of development, this kind of grid of city lights. And past that lies the desert, where you just see sandstorms and bare mountains. I wanted to really occupy the space, I wanted it to be a work that existed in a quite existential way, removed from its surroundings.

Doug Aitken: ‘Mirage’ 2017, Desert X installation view // Photo by Doug Aitken Workshop, courtesy the artist and Desert X

BAL: How did this manifest in the context of the ‘DesertX’ exhibition?

DA: It became a living sculpture. A living installation. It’s changing continuously, from dawn to dusk to night, and the landscape around it becomes the work. The exterior of the sculpture is cloud and entirely mirror; the interior is made of 8 rooms and every room is also completely mirrored. It’s a kind of labyrinth. We designed it in a way where the aspect ratio was very specific for the different views and perspectives that you find outside. But there’s also moments that are disorienting or almost violent in their multiplicity of views, where you reflect infinitely. It becomes like a particle excelerator, in a way. I saw it as a time piece and an encounter that the viewer goes to, but then merges with and almost becomes it. Within that experience, there’s a compression of the exterior landscape and you. I think, in a lot of ways, the piece ends up being a quite abstract experience.

It’s an unusual encounter in that the architecture has no windows or doors: it’s just open to the elements. We were there filming and there was a very intense sandstorm that from the north and you could just feel the granular wind gusting through the corridors of the house, almost rubbing on your skin. It was so interesting being in the space in a condition like that, and seeing these elements invading and permeating the experience.

BAL: What is your relationship to the art historical tradition of Land Art? How might this movement be updated in contemporary art practices?

DA: I think when we look at a lot of the trajectory of Land Art from the 60s and 70s, it’s often quite abstract. It uses geometric shapes and forms, such as in ‘Lighting Fields’ or ‘Double Negative’ or ‘Spiral Jetty’. And that has a certain quality within the landscape, looking at monumental patterns and geometry. But ‘Mirage’ is very different because the form of this is very surreal. I noticed people encountering it have very little resistance because the shape is so familiar. Everybody’s been inside of a house like this before. But inside all of the familiar things are erased; only the forms and the dimensions are retained.

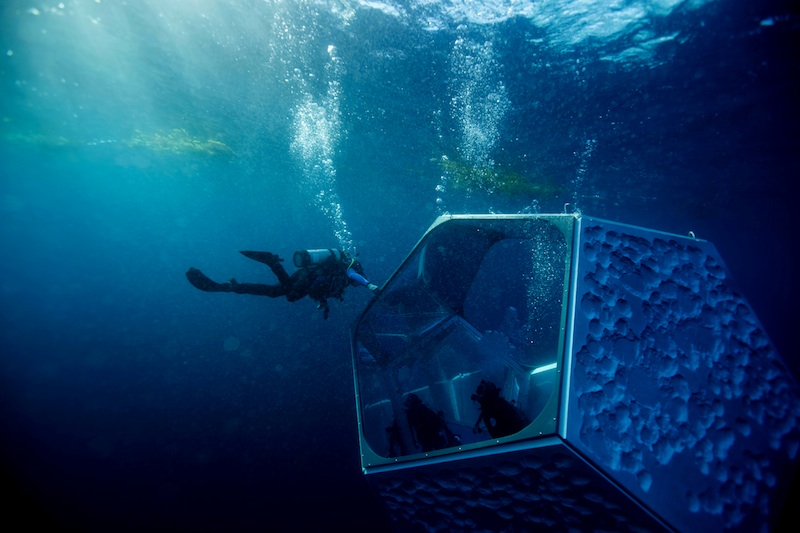

Doug Aitken: ‘Underwater Pavilion’, 2016, installation view, Avalon, California // Photo by Patrick T Fallon, courtesy of the Artist, Parley for the Oceans and MOCA, Los Angeles

BAL: Your recent project ‘Underwater Pavilions’ off the coast of Catalina Island is co-presented by Parley for the Oceans. Tell us about this project. How do you collaborate with organizations to raise awareness about the state of the oceans?

DA: ‘Underwater Pavilions’ touched on some similar subjects. With both ‘Underwater Pavilions’ and ‘Mirage’, I was interested in not only making works that were systemic, but also making works that were successions outside of the gallery system or museum environment. I was restless with this idea of the confinement of the architecture of the current cultural system. The way America moves is that it kind of continuously moves West and then stops about 1/2 a mile from here. That demarcation line is just geographic. I found myself continuously going out to that line. That’s my border. It’s at the edge of the city where it meets the coast and there’s just the horizon. What the desert was to the Land Artists in the 70s, maybe that horizon out there is a space that can really be addressed. When we see that 70% of the earth is underwater, we realize that this huge topography is there that we know so little about. Is it possible to create an artwork that creates an aperture into that? That was the beginning of the ‘Underwater Pavilions’ idea.

The idea was quite clear, but it was almost impossible to figure out how to do it. It was such a conundrum. Who do you ask to use part of the Pacific? Do you get a permit? Do you have to do paperwork? Do you need insurance? Can you just do it yourself? There was nowhere to go or no person to really ask about this. We wanted to make 3 pavilions that would float 10-30 feet underneath the ocean’s surface. They were tethered to the ocean floor. We wanted them to be a combination of a rough aggregate surface that sea life could cling to and they could become a living ecosystem, and then also mirrored surfaces. So they would kind of kaleidoscope the sun coming through the surface, the underwater landscape and kind of pour these into these large scale encounters or abstractions. One thing led to another and we met this ocean conservation group, Parley for the Oceans. It was a really great and fortuitous dialogue.

I think Parley for the Oceans really valued the collaboration for an artwork that was driven by ideas. This was a way to create a collaboration between culture and contemporary art, and oceanographers and marine awareness associations. For all of us, one of the things that was a collective belief was the interest in seeing if this project could create a door to the ocean. To visit this work, you have to go under the ocean; you have to literally swim at a minimum or dive to deeper levels to encounter these works.

Doug Aitken: ‘Underwater Pavilion’, 2016, installation view, Avalon, California // Photo by Patrick T Fallon, courtesy of the Artist, Parley for the Oceans and MOCA, Los Angeles

BAL: Why is it important to connect with these more natural phenomenon?

DA: I think for the last decade we’ve been fed this idea of synthetic and virtual reality dominating. I actually find the opposite to be true: I find there’s a return to the real. I think for many people there’s an intense desire and a reawakening to natural systems and the physical world. We’re looking around at the tactile things. For me, the first time I dove the Underwater Pavilions, I’ve actually never had a more hallucinatory experience in my life. It was November and the ocean was cold and it was windy and there was a kelp bed, and you’re kind of climbing under this kelp bed under the ocean.

Doug Aitken: ‘Underwater Pavilion’, 2016, installation view, Avalon, California // Photo by Patrick T Fallon, courtesy of the Artist, Parley for the Oceans and MOCA, Los Angeles

When I think about almost every art viewing experience I’ve had, I’ve either been sitting or standing and there’s a floor underneath me. Then, all of a sudden you find yourself in slow motion, horizontally, climbing through space, through this dark blue void. You’re seeing clues, you’re seeing some huge kelp forest in the distance that you could meander through. As you’re moving through this world, you can see this hexagonal object in the distance and you kind of move towards it, and as you approach you’re almost flying through this subconscious space, yet it’s so real. You could pick up a barnacle encrusted rock and slice your finger in a second. That idea, that immediacy and that connection back to reality, was very unusual. I think in a lot of ways, my personal interest is in seeing art create systems, living systems. Or seeing art that is continuously in flux and is reinventing itself with or without us. One inescapable system for us is time: the idea that an artwork can live in that continuum and not be frozen is very compelling.