At the end of my conversation with the artist and activist Madeleine Kate McGowan, she brought up a phrase of Joan Didion’s—something along the lines of, ‘The closer you get to something, the less dangerous it becomes’. From the beginning of her practice, McGowan has been altering the traditional proximities of performance: the actors and audience meet without demarcation, and together they craft a world. Rather than the detached position suggested by the word “audience”, she used the word “guest” to describe those interacting with her performative works. These encounters have been staged in 4-story buildings or single apartments in Copenhagen, or launched from the roofs of New York City, with the flight of hundreds of balloons containing invitations. In 2015, she initiated the documentary series ‘Other Story’, interviewing people living through zones of crisis: members of Standing Rock’s Lakota tribe, or refugees arriving to Lesbos. Throughout her entire body of work, there is the notion that structures designating what is dangerous or not, who belongs in Europe or not, can be intervened upon. All that is needed is a human encounter.

Documentation from Five Apartments, 2014 // Photo by Fryd Frydendahl, courtesy of Madeleine Kate McGowan

Nat Marcus: You started doing performance work with SIGNA, the immersive performance group. Did it disrupt your notions of what performance art could be?

Madeleine Kate McGowan: The moment I stepped into a SIGNA performance was the moment the world of my own work was born; I didn’t even desire to work with performance before that. It was in 2004, and the piece was called ’57 Beds’. This is actually where I met my collaborator Inga Gerner Nelsen, but she was in the fiction, performing. I ordered a raspberry soda, and she served me pineapple, and I totally fell into the trap: I was like, “Excuse me, I ordered raspberry”, and she just said, “No, you didn’t.” And I said “Yes, I did” and she just kept looking at me and said, “Yes, you ordered pineapple.”

My involvement in these performances gave birth to the idea of society, structures of identity, nation and history, as fiction. And I could, as an actor, work with that as material, manipulating our approaches to these systems and my own body within them. It started as playful activism, not as a pronounced statement of entering the art world. Rather, it was a community of people interested in the same methods, opening fictional spaces in places people didn’t expect—in construction sites, on the streets.

NM: I first encountered your work with the ‘5 Apartments’ performances in 2015, for which guests signed up for an hour inside an apartment containing a fictional world. How did you strategise intercepting the realities of these guests, and how do you consider the ethics of that action?

MKM: For ‘5 Apartments’ I wanted to see what would happen if the performers had a more abstract sense of that notion of playing with fiction and reality. I would decipher reality as a chain of situations that are predictable: it’s an idea tightly connected to predictability and consistency. Structures and patterns are performed and carried out to produce reality. So manipulating that chain is what one could call working with fiction. It’s a balance, because the moment you open up the unpredictable and unknown, that’s when you can tap into uncanniness. Some people react to this with fear, others are seduced. I wanted to open up the unknown with something as quotidian as ringing a bell and entering an apartment upstairs, but not knowing what you would be entering. We trusted that something as simple as the stranger walking in and seeing someone washing their hands could be poetically loaded.

NM: It’s already enough to create a disjuncture.

MKM: Yes, and we trusted that you didn’t need to add all this stuff, all these objects. Coming from the performance scene in Denmark, this was a break from my schooling. I didn’t want be dependent on using objects to create a fiction, or destroy it: as a SIGNA performer, you don’t have nightmares of forgetting your lines. It would be a dream of standing in your old-world nurse’s uniform, about to receive the guests, and looking down to find a can of Pepsi MAX in your hands.

I wanted to challenge that dependence, and really just play with the everyday scenography. Taking the elements of that chain of predictability, and shifting them just a little, you would thicken the air. I also wanted to move away from my training that would put guests in such a vulnerable place, not knowing the rules of fiction enforced by the whole ensemble. There’s a streak of fascism in this, and I wanted the performers to be just as vulnerable.

Documentation from Five Apartments, 2014 // Photo by Fryd Frydendahl, courtesy of Madeleine Kate McGowan

NM: There was only a mutual gauging of the fiction, like walking down stairs in the dark and constantly expecting there to be another step, but not being sure.

MKM: It was also a lesson in the dangers of the aesthetic space that could be opened up. During the last night, the fifth apartment, we set off the whole building’s fire alarm by accident. It’s important, on the one hand, to have the liberty to create such a space: the guest entering an apartment utterly filled with cigarette smoke. But I think the performers going into a day-long performance like that need to be conscious of what’s happening to them, and the space itself. When you’re performing and you go into that very aestheticised mode of being, everything can just become an image: the fire is beautiful, and suddenly the whole apartment could be up in flames.

NM: What I found so effective was this silent negotiation going on between the performers and the guest: feeling out each other’s willingness to press into fiction, and gauging when our aestheticised visions of the world were turning off or on.

MKM: One of the inspirations in our process was something that the choreographer Mårten Spångberg called “octopus art”: the octopus being a metaphor of a creature in darkness, the deepest sea. And when you are in darkness, nothing is given a name, nothing is titled yet.

NM: Like Eden.

MKM: Exactly, and it is also the place where nothing can be sold, because it cannot be pronounced in an office or a pitch meeting. So, to nurture this space of darkness is a method of challenging the capitalist paradigm, in which everything is in light, everything can be packaged, named and sold. This was our main focus in the whole process of opening these apartments: being able to embrace the octopus’ space, not having to explain everything, but still being able to communicate within the darkness.

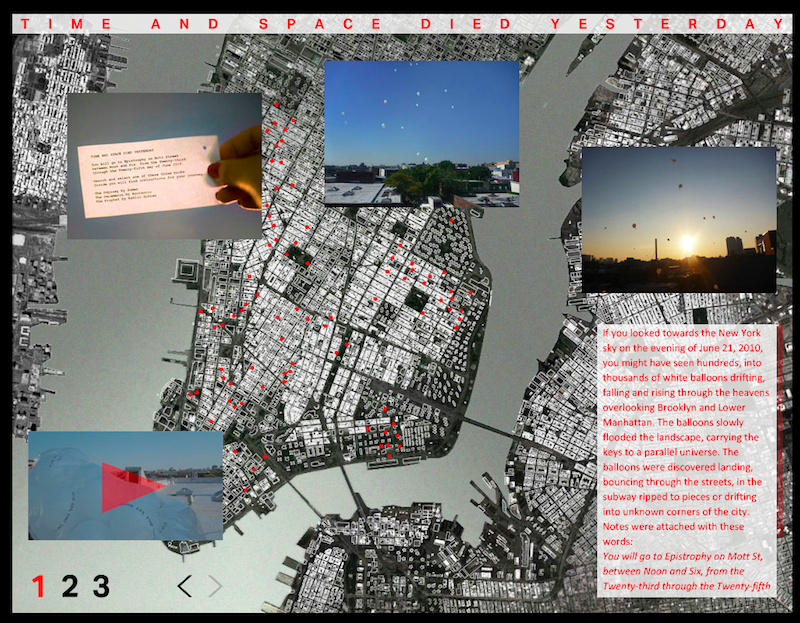

From the project ‘Time and Space Died Yesterday’ // Courtesy of the artist

NM: You’ve also worked in even more open-format interventions: ‘Time and Space Died Yesterday’ took a large chunk of lower Manhattan and Brooklyn as the stage. But would you say, rather than it being a question of degrees of openness, that these are just different approaches to manipulating the structures of reality?

MKM: I would. Doing so without a reliance upon high production costs or external funding. Rather, we wanted to point to a detail of reality, or ring one of its chords, and from that, open up a poetic and chaotic universe. And between these delicate touch points that strung up the performance (like inserting a performer in a Chinese restaurant to which the guests were directed), everything started to be affected. We opened something up in the way the guests navigated the streets; it was infused with fiction because people didn’t know what was part of the performance or not. It was only two of us organising the work, and people really thought we were an army of performers.

NM: You mentioned pointing to something, or making someone alert to something, as a means of opening their eyes to the poetics of reality. And, at same time, there’s a danger in delving so far into these poetics that everything becomes aestheticised. I’m curious as to how these things play into your thinking about ‘Other Story’. In a way, you’ve been crafting other realities throughout your whole practice, worlds in which you have to negotiate an ethics of showing something that’s exotic or “Other”, and still not letting it be stripped of its humanity. How did you come to film people telling their stories, and how do you trace your ethics developing from performance into this type of project?

MKM: I was listening to the radio a few years ago and heard an interview with a woman who had arrived to Italy from Libya. She was holding the microphone and telling things from her perspective, and there was a moment in which I questioned why she was given the possibility to express herself on-air, and not merely mediated by the reporter. The fact that I had internalised this question was a sign of how indoctrinated I was. I couldn’t just project the catastrophe into the future, thinking at some point the Danish media would be taken over by conservative, racist points of view. We were already there; it had already immersed me in its discourse. ‘Other Story’ began as a kind of exorcism of that discourse from my own mind. It wasn’t pointing fingers at anyone else, but placing myself in a situation that would shake the crystallisation of that paradigm I’ve inherited in Denmark. I would willingly enter a crisis, and with my tools, show an encounter I had with a person I didn’t know: a person who represented a group of people who are othered and dehumanised in Europe.

In terms of the aesthetics of ‘Other Story’, I knew from the beginning that I didn’t want to add any music and I became more conscious of how much music there is in documentaries, or short viral films on Facebook from Al Jazeera, for example. It’s vulgar. It creates a distance, because misery has no soundtrack. When you come to Lesbos’ shore on your inflatable boat, there’s no orchestra in the background. If our relationship to crisis always comes with a soundtrack, we will never think we are there; we’re waiting for the soundtrack. I just wanted to use the sounds that were there—the wind, the water. I’m still cautious about things like colour-grading or adding contrast in the image. The interview questions themselves are like a skeleton of the project, the pulse to the whole documentary project.

In all my performances, I’ve always worked with the encounter. Meeting a person is one thing, but an encounter is a kind of loving violence: you don’t forget it. So it’s a natural progression that ‘Other Story’ tracks the encounter I have, and then the encounter travels through film. And I think it all relates to the idea of working within the darkness. Not in a Christian sense, not “evil”.

NM: No, just the unknown.

MKM: Exactly, the unknown is an area of crisis. And the closer I got to it, the more this conservative depiction we’re receiving in Europe began to dissolve.