Article by Jack Radley // Jan. 13, 2018

How do we heal our wombs? This investigation is central to the work of Tabita Rezaire, a Johannesburg-based video artist, Kemetic/Kundalini Yoga teacher, and digital healing activist. Through cosmic sutras of humor and history imbued with internet aesthetics, the artist tackles reproductive justice, racial violence, and spiritual well-being in her video ‘Sugar Walls Teardom.’ This work, recently shown in Berlin at 3hd Festival at HAU, addresses institutionalized violence against Black women and the emotional and ancestral trauma of wombs from the colonial, patriarchal, and capitalist systems whose medical research (largely by white men) came from abusing slave women’s bodies. Rezaire chatted with Berlin Art Link to discuss her practice and the revelation of truth through unlearning, which for her is a method of healing.

Tabita Rezaire: ‘Sugar Walls Teardom’ (still), 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Jack Radley: Could you talk about your video, ‘Sugar Walls Teardom,’ which was included in ‘Whatever You Thought Think Again’ at Hebbel am Ufer?

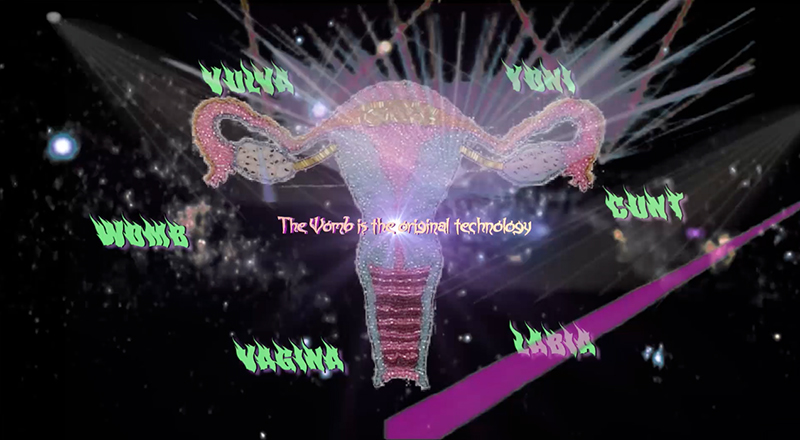

Tabita Rezaire: That work is a celebration, an offering to the wombs that have contributed to the states of my womb today. It’s about the contribution of Black womxn’s wombs to the history of science and technology, and how their contributions have been erased from that history and have not been acknowledged. The work is a rewriting of a history, a celebration paying homage to them, to their work, which often was forced, and to their lives and the power of their wombs that affect me today.

We carry a lot in our wombs. Things get passed down from womb to womb, especially wounds. That makes it a vulnerable yet powerful space physically, emotionally, and energetically—a center, a receptacle, a storage womb, a hard drive. My video is looking at what information is stored in this hard drive–what is useful for us and what can be deleted? This work was a contemplation on how, as a Black womxn, you relate to that space within yourself, as a personal experience. Why are the wombs of the people around me so traumatized? How does that womb trauma affect us? Looking at it through the history of technology is what this work explores.

JR: So how did you first begin exploring these topics?

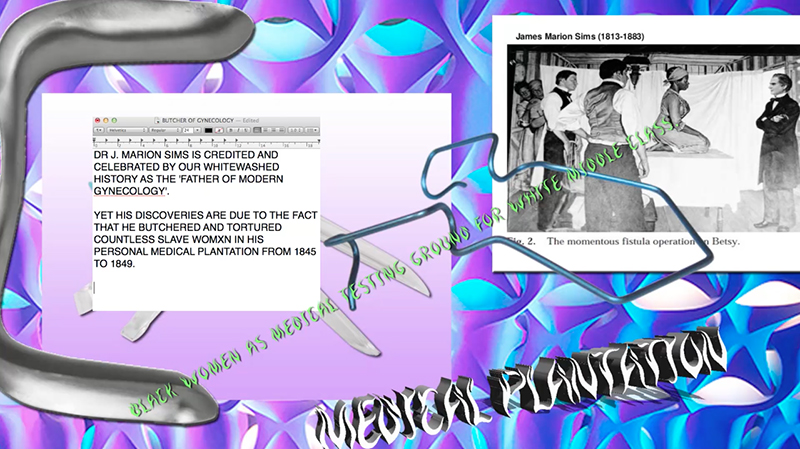

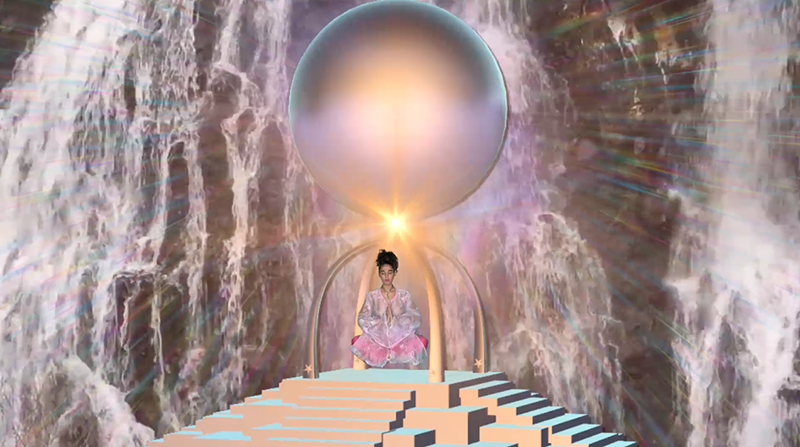

TR: The work started with looking at the history of modern gynecology and the history of veneration that exists about Dr. J. Marion Sims, who is considered the face of modern gynecology. You have statues of him everywhere in the U.S. and he’s in all the history medical books as the guy who started the first hospital for womxn and the savior of womxn, basically. But what’s not really told is that a lot of his discoveries are due to the fact that he literally butchered many enslaved womxn. He had his own medical plantation in his backyard, during slavery in the U.S., and he collected sick womxn slave workers and did experimental surgery on them, and so many of them died in the process. This lasted for years. How can you be a defender of womxn when you’re using and abusing Black womxn? The work is looking at that landscape of the literal torture of Black womxn and the exploitation of their own creative centers and how we are still affected by it. The other part of the work is a healing womb meditation to compensate, transform, and release those blockages.

Tabita Rezaire: ‘Sugar Walls Teardom’ (still), 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

JR: When you’re doing research for projects, how do you go about uncovering the truth?

TR: I think information finds me. I believe ideas or information or ‘truths’ are entities in themselves and they want to make their way out into the world through people. They choose different people as vessels to spread. It’s also a matter of energetic or vibrational frequency—when your being operates at the same frequency as that specific information, you can grasp it. That’s what I believe happened. Also, for me, the womb is a portal to receive information, to download from our hard drives and all the knowledge and wisdom that is stored in them. I tapped into it somehow and that allowed me to find the information, or the information to find me.

JR: What’s your process of making videos like?

TR: First comes the research. My work is very research-based, so I spend a lot of months researching a certain kind of field or area. And only then, when I feel like I have a tale to tell, I think about the visuals. I sit on my open timeline, and then I collect loads of image, videos, texts, notes, and cruise on the internet for days. Then I build up a visual for that story.

Tabita Rezaire: ‘Sugar Walls Teardom’ (still), 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

JR: Do you think the internet has borders?

TR: The internet definitely has many borders—who has access to it, how one has access to it, at what price, at which speed. It’s a very bordered territory, only 51 percent of the whole world this year is connected to the internet. That’s not borderless. On the whole African continent, penetration is only 31 percent, and then within each country the way you access the internet and the content you can access is very different. There’s a lot of censorship or filtering, and on a different level, you’re very constricted by the algorithmic process that’s in place. So my experience of the internet is probably very different than yours. The borders are multilayered.

JR: How do you determine which videos are publicly accessible online and which are not? Does the way in which people experience your work, either online or in an institutional space, matter to you?

TR: Which are available and which aren’t is an admin thing for me. I have an idea for this website, or a page on my website, like an online show, a platform for my recent videos to exist online. I haven’t made the time to do it, but I want them to be accessible for as many as possible. It’s just like a dream deferred and I may just take the password off. In terms of experience, it feels more intimate to be watching a video one-on-one in your bedroom than to be with loads of museumgoers. But for me, it’s not important. I thought it was at some point; I had one work that was a hologram, so I didn’t think it would work to see it online, but I made it in 2015 and now almost no one’s seen it. Not everyone will have the resources, even museums, to put it out the way it was intended. So now I took the password off and it doesn’t matter. It’s just a different experience, but it’s valid in itself.

JR: So much of your work is about shared knowledge and producing new knowledge. The particularities of how it’s seen seem less important than the knowledge itself.

TR: When I make work, it’s like birthing something. After, the work has its own life, independent of you. You can’t control where you kid is going, who they’re going to hang out with, or what they’re going to become. You put something out there, and the work has its own becoming–I don’t know who will watch it, how, where, etc. It doesn’t matter. My responsibility is to build it, grow it, birth it, and put it out there.

Tabita Rezaire: ‘Sugar Walls Teardom’ (still), 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

JR: Can you talk about unlearning as a form of healing?

TR: It’s necessary, because we have internalized so many toxic and harmful mechanisms of being and living. To not reproduce how these mechanisms have wounded us, we need to unlearn and let them go. The way we are, the way we behave, the way we talk to ourselves and each other is dreadful–and that’s because we have been taught to be as such, and because it’s frightening for many of us to change and to break those automatic patterns by which we are wired. It’s unlearning on so many scales, not just historical narratives of time and space, but also on an emotional level–how do we deal with our emotions, how do we react when we are emotionally triggered, how do we communicate as people or with ourselves? Everything has to be unlearned, and that’s also about letting go of what no longer serves us to make space in ourselves, within ourselves, our communities, our world, for different patterns, perspectives, understandings, information. We need the courage and grace to walk the journey of self-respect, self-love, and self-compassion. When you operate at the vibrational frequency of love, then hurtful patterns, negative thoughts, doubts, and fear-based behaviors won’t reach you; they’ll just slide off you because you’re there. That’s unlearning, and that’s healing.