by Jack Radley, studio photos by Yishay Garbasz // Jan. 26, 2018

The scintillating colors and intricate compositions of Corinne Wasmuht’s paintings confront the clarity of her pristine studio space. Sheltered by the stillness of white walls, her paintings rest in the former bedrooms of an Altbau apartment in Kreuzberg. The artist removed doors and knocked down walls to create two spacious rooms for painting, a kitchen, and seating area for computer research. The large windows’ closed shades block any hint of January sunlight in Berlin. Artificial overhead lighting and computer screens illuminate the working area, mirroring the synthetic luminosity of Wasmuht’s paintings.

Each work breathes on its own wall; the artist sometimes even hides paintings in other rooms so she can dedicate her focus to creating the image at hand. “I focus on one painting one week, and then I go back to another one and see it with new eyes because I was inside that other painting,” she says. Like her intended viewer, Wasmuht does not stand in front of her paintings, but rather “inside” of them. The monumental scale of her wooden and aluminum panels, cosmic color combinations, and systemic conflation of space consume viewers, who often move backward, away from the wall, to find an entry point into the work. Wasmuht, who changes studios every five years, also recently stepped back from her practice to reassess the size of her team: she downsized from managing five assistants to producing all of the work herself.

“There is no concentration when you have a lot of people working for you. You are like an orchestrator conductor: ‘You make this! You make that!’” she explains, rhythmically waving her steady hands. “I was not focusing on my paintings themselves. I was focusing on the assistants, so I decided to cut it all and go back in a smaller studio and focus only on painting and not managing.”

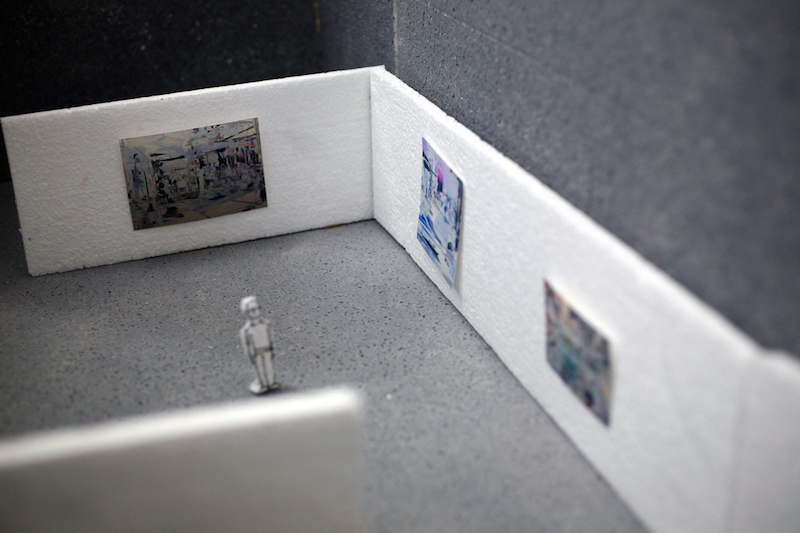

This solitude allows for extra attention on the paintings. For better or for worse, engrossed in working, she slept in the studio last night, and I am lucky that she takes the time for a studio visit in the days preceding her show at König Galerie. The exhibition space bears no influence on her work. In fact, she says the reverse: the rooms are built for her paintings. She points to a model of the Nave of König’s building, St. Agnes, with white gallery walls constructed inside of the Brutalist church just for her six paintings.

Wasmuht’s multi-paneled panoramas, up to 6.4 meters in length, engross viewers and challenge the optics of their perception. She explains that science and mathematics suggest that the world may have 11 gravitational dimensional fields, but we can only perceive three. Wasmuht explores the space “behind the mirror, the space behind reality.” Airports and industrial lobbies coalesce into heterotopias, in which the confluence of people and ideas emerge and dissolve in glitches of paint. In her paintings, networks materialize in a compressed temporality of simultaneous spatial and temporal dimensions. Wasmuht’s paintings are inhaled in various breaths and do not lend themselves to rational analysis; amidst the overwhelming scale and saturation of color viewers begin to recognize distinct fragments in a plexus of characters, structures, and reflections.

Wasmuht describes her finished paintings as film stills laid on top of each other, an intuitive process that in the end yields “something that remains without time.” While in film, individual stills are consecutively combined to create moving images, in her painting, every still is conflated into a single image. However, this insight only comes post-production, and these revelations do not create formulas for success. “I can’t say now, ‘I’m going to make a film in a painting, compressed without time.’ As soon as I say that it doesn’t work because the invisible is missing,” Wasmuht says. “Painting is always dealing with the invisible, what you don’t see.” Wasmuht paints to describe the intangible, and thus she hesitates to define the content of a singular work in words (if she could, she says, she would be a writer). “In the end, there’s always something intuitive that is supra-subjective that one can feel. You can’t describe it in words, you only understand by looking at it.”

Computer technologies have facilitated the compressed montage of Wasmuht’s recent paintings. The artist, who formerly worked with an analog, hand-cut collage method now works with repositories of images in Photoshop layers to explore trajectories for her paintings. “As soon as you cut the photos, they are destroyed in some way, whereas on the computer you can save every step you are doing,” she notes. In Photoshop, Wasmuht delves into quixotic vignettes of possibility, a mode of working that preserves her source material. However, she eventually turns away from the screen to focus exclusively on the painting. “At the end, the painting has nothing in common with the computer image. It’s completely different,” she says. She constantly explores new ideas and returns to old themes, comparing her process to an ouroboros—the ancient symbol of a serpent eating its own tail.

“I make my paintings to be an evolution of myself, to grow inside, and not just to make a lot of production,” she says. “Gallerists always want to have a lot of paintings to bring to art fairs. They’re always telling me, ‘If I don’t show you this year, everyone will forget about you,’ which is a lie. Really, they just want movement.” Wasmuht will often work for an entire year on one painting, and rework paintings she had started years before. It is precisely this individual attention, this devotion, to each painting that produces brimming imagery that is balanced but not scattered.

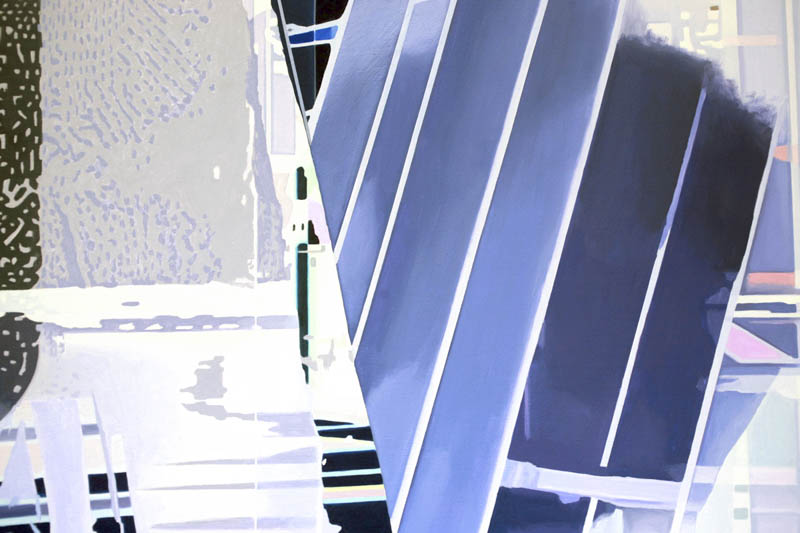

Carefully considered pigments vibrate in a mise en abyme of everyday space on her aluminum and wooden panels. In ‘oT’ (2017), rich warm blacks of magenta and turquoise pop in sparing accent areas, whereas in ‘U2’ (2012–2017), Wasmuht leverages the weight of a cool, unmixed ivory black to create a flat, screen-like illusion. A master of temperature and saturation, Wasmuht often employs hue, as opposed to the viscosity of the paint, to creates weight and depth from her skillfully balanced palette. The white areas of her paintings perhaps first appear as glitches of undeveloped negative space; however, upon closer analysis, viewers start to read them as mirages, reflected as positive forms. The transmutation of positive and negative space approximates the dynamism of film, presenting the panel as a screen itself. In the large format of traditional panorama paintings, Wasmuht transforms the landscape into technoscape, in the Appaduraian sense of the word, in the revelation of new cultural interactions and exchanges occurring at unprecedented technological speeds.

After leaving Wasmuht’s studio, I head to Gleisdreieck, the nearby U-Bahn station that is the convergence of the U1 and U2 lines. The everyday site hosts busied travelers at hurried and relaxed speeds, bustling up the stairs to a platform where light floods in from the glass ceiling. A train approaches at a rapid pace, and at first I don’t know where to focus my gaze. Perhaps not so coincidentally, ‘U1’ and ‘U2’ are the titles of two works in Wasmuht’s upcoming show. At this junction, I begin to understand Wasmuht’s work with new eyes, but underneath the dull grey sky of a Berlin winter, I long to be inside the vibrancy of one of her paintings.

Exhibition Info

König Galerie

Corinne Wasmuht

Exhibition: Jan. 20–Feb. 25, 2018

koeniggalerie.com

Alexandrinenstraße 118–121, 10969 Berlin, click here for map