Article by Jack Radley in Berlin // Feb. 7, 2018

Mark Dion is in the midst of publishing what amounts to a small library right now, from ‘Apparatus: Carte Blanche no. 2’ to ‘Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World to The Incomplete Writings of Mark Dion—Selected Interviews’ and ‘Fragments and Miscellany.’ The latter anthology’s “incompleteness” does not speak to a lack of thorough compilation, but rather to a trailblazing ambition for the work to come. In his current intervention ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work’ at Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Dion inserts the scientists’ tools alongside the permanent displays of their findings. In this process, he conducts an ethnographic investigation of the Museum’s collection, the practice of field work, and the lives of the workers themselves. The artist sat down with Berlin Art Link to discuss the importance of artistic writing and the curatorial nature of his work.

Mark Dion: ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work.’ 2018, as part of ‘Kunst/Natur: Artistic Interventions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin’ // Courtesy of the artist and Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Photo by Hwa Ja-Götz

Jack Radley: What is the role of publishing in your practice?

Mark Dion: Publishing has always been a priority for me. My early encounters with contempory art came largely through reading. It forged the idea in me that artists wrote and book making was an important aspect of the practice. The only concrete goal I have as a professional artist has been the desire to occupy 30 centimeters of shelf space in the library. That was the most concrete expression of success I could imagine.

So I put a great deal of energy into books I make and the books others have made about me. I work closely with authors and designers. I often design books by hand, making a hand-drawn design template which forms a template foundation for the designers to build on. The designers I work with most of the time bring ideas to the table but also can follow instruction if I need something to be a particular way.

Mark Dion: ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work.’ 2018, as part of ‘Kunst/Natur: Artistic Interventions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.’ // Courtesy of the artist and Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Photo by Carola Radke

JR: There is a long history of the artist as writer, from Donald Judd and Robert Smithson to Martha Rosler and Coco Fusco. Could you discuss the evolution of your approach to writing as well of some of your favorite artist-writers?

MD: Most of the artists I worked closely with as a student, like Thomas Lawson, Joseph Kosuth, and Martha Rosler, wrote as part of the practice. I think for many of them, like Vito Acconci and Dan Graham, writing was a way to demystify art making and take it outside of the mythic realm of genius and inspiration. Of course, it’s obvious that artists write in ways that reflect their practices as makers. Smithson’s writings, like those of Hollis Frampton, are complex in structure and pull from and mash up a number of disparate sources. Rosler’s writing is urgent and edgy, as is her work. Fusco’s is angry and smart but also laced with humor, as her art is. My writing is peripatetic, mimics other forms, and can be deeply ironic, as my work is.

Mark Dion: ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work’, 2018, as part of ‘Kunst/Natur: Artistic Interventions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.’ // Courtesy of the artist and Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Photo by Hwa Ja-Götz

JR: The ‘Incomplete’ writings cover almost all of your practice, but do leave some aspects out—including teaching. Could you talk about the role of teaching and education, at Columbia University and Mildred’s Land, in your practice?

MD: Teaching has been a productive aspect of my practice for more then 30 years. It is not particularly sustaining financially, and I don’t depend on it materiality, but it does keep me sharp and updated on the changing debates and concerns within the visual arts community. It is easy to tell when an artist does not have contact with students; they become kind of rusty, isolated and intellectually arrested in their moment.

JR: In ‘Carte Blanche no. 2’ you highlight apparatuses for fieldwork, from guns to specimen jars. What are the apparatuses of a skilled teacher?

MD: The apparatus of a good teacher is not so much a group of things but rather a skill set which allows the students the space to express, lead, and become unguarded. My teaching method is remarkably simple: put interesting people, places and things in the way of the students and step back. I try to construct a situation in which the students can productively hang out and build sustaining relationships while introducing them to the idea that they are surrounded by intellectual resources that are easily accessible.

Mark Dion: ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work.’, 2018, as part of ‘Kunst/Natur: Artistic Interventions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.’ // Courtesy of the artist and Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Photo by Hwa Ja-Götz

JR: Your recent retrospective at the ICA/Boston included ‘Men and Game’ (1998), a series of 161 found hunting photographs. In your own words, your work often explores the “culture of nature” that we humans have created. Do you think this culture is gendered?

MD: We construct what gets to stand for nature. As societies we forge a kind of cultural consensus, but it is entirely possible that within a society there can be a lot of fragmentation and disparate notions. What nature means for a farmer, scientist, hunter and witch may mean very different things entirely. Indeed there are often radical variations within individuals in these groups.

A work like ‘Men and Game’ explores a pictorial convention—images of men (mostly) with the carcasses of the animals they have slain. While I do not entirely condemn hunting, I am always suspicious of an activity which so throughly links pleasure with killing. The fact that the collection of photos is all men except for two would seem to argue that the convention of gloating over the corpse of the animal one has dominated and exterminated is primarily male. This was not a choice; this was what the data of the photos demonstrated. The title came later. Almost without exception, I have only found pictures of men with game.

Mark Dion: Men and Game, 1998, framed photographs in various media, 120 parts, dimensions variable // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie für Landschaftskunst Hamburg // Photo by John Kennard

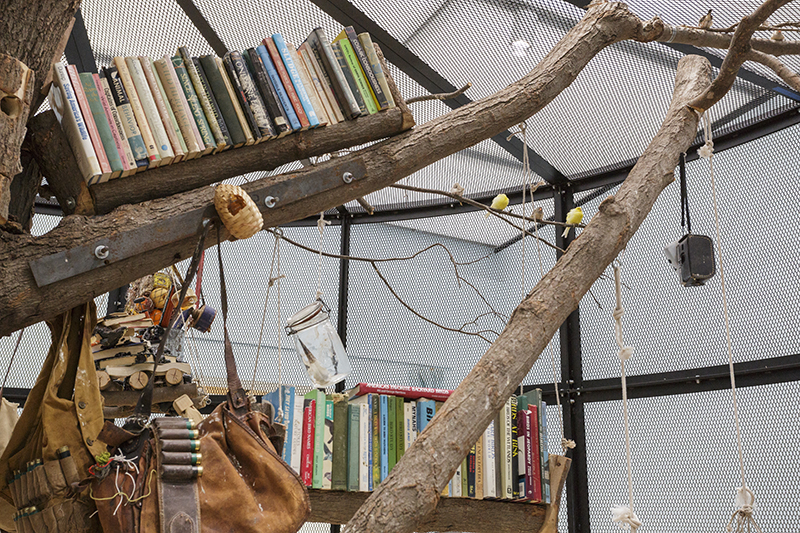

Mark Dion: ‘The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts’ (detail), 2016/2017, steel, wood, books, living birds and found objects, 350,5×609,6cm // Courtesy of the artist and Sammlung Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich // Photo by John Kennard

JR: In ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Fieldwork,’ you display the equipment that scientists and researchers have used across times in the public museum collection. For me, this evokes Fred Wilson’s ‘Mining the Museum’ (1992–93). We’ve talked about the artist-as-writer, but let’s talk about the artist-as-curator…

MD: Fred Wilson and Lisa Corrin’s ‘Mining the Museum’ is one of the most important exhibitions of the 20th century. Fred was able to work with the collection of a pretty conservative and stagnant institution and make them a better, more democratic, more honest, more exciting museum. In many ways, those of us who work in this vein are walking through a door that Fred opened for us.

I have curated some pretty remarkable projects, but always in collaboration with others. The process of collaboration is essential to my curatorial endeavors. I worked with the curator Sarina Basta on ‘Oceanomania’ at the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco and Musée Océanographique de Monaco, and we co-curateted ‘ExtraNatural,’ an exhibition which demonstrated the supernatural in the temple of the Enlightenment, at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. At New York’s The Drawing Center, I worked with Madeleine Thompson and Katherine McLeod on ‘Exploratory Works,’ an exhibition about William Beebe and the Artists of the Department of Tropical Research. This project featured art, films, and artifacts from the tropical jungle and ocean expeditions of Beebe’s remarkable team. For ‘The Academy of Things,’ Petra Lange-Berndt and Dietmar Rübel were my chief collaborators and we explored the culture of the academy and nature in Dresden. Here in Berlin, I worked with the scholar and art historian Christine Heidemann. Together we looked at the natural scientists associated with the museum as an ethnographer might approach a distinct society or tribe—a group with particular beliefs and material culture.

JR: So would you say there is a curatorial dimension to your artistic practice?

MD: I honestly don’t see a vast difference between exhibition making, in a curatorial sense, and art making. However, often curators approach their endeavor with a science-like rigor which can get in the way of making provocative but enlightening connections. Artists have no obligation to be scientific or even to tell the truth. The freedom to be speculative, experimental and associative can lead to marvelous exhibitions. The best exhibition I’ve experienced was Mike Kelley’s ‘The Uncanny’ made for Valerie Smith’s Sonsbeek in 1993. No doubt this had a huge influence on my belief that artists can be exceptional curators.

Exhibition Info

MUSEUM FÜR NATURKUNDE BERLIN

Mark Dion: ‘Collectors Collected. The Material Culture of Field Work.’

Intervention: Jan. 30 – Apr. 29, 2018

Invalidenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, click here for map

WHITECHAPEL GALLERY

Mark Dion: ‘Theatre of the Natural World’

Exhibition: Feb. 14 – May 13, 2018

77–82 Whitechapel High St., London, click here for map