Article by Jess Harrison // Friday, Feb. 23, 2018

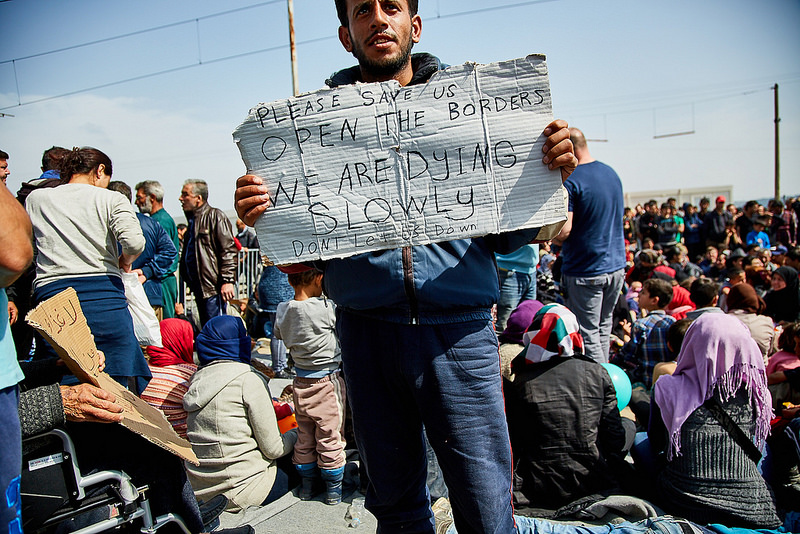

Artist, activist and filmmaker Tomáš Rafa deals with the contemporary political reality of Slovakia and other Central European countries in his work. Shown last year at MoMA PS1, ‘New Nationalisms in the Heart of Europe’ is his archive of photographs and videos which depict alt-right protests, the migration of refugees and social art projects within the Roma community, a dispersed ethnic group that originate from Northern India. Despite their overt political tones, Rafa remains passive when presenting his works, which all focus on the four nations of the Visegrád or V4 Group (Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland). These countries only joined the European Union in 2004 and the emerging tensions between the recently implemented democratic structures and non-democratic regimes of their past are something Rafa’s work consistently captures.

An exhibition of his work opened at the Kunsthalle Bratislava last week. Curated by Lenka Kukurová and entitled ‘Paradox of Tolerance’, it uses footage from Rafa’s archive to explore limitations on freedom of speech, using as its framework the work of philosopher Karl Popper. Before the show opened, Rafa spoke with Berlin Art Link over Skype about democracy, the refugee crisis and the increasingly indistinguishable boundary between legality and illegality as far-right parties become part of official politics.

Tomáš Rafa: ‘March of nationalists and far-right radicals during Polish Independence Day in Warsaw, Poland,’ 2016 // Courtesy of the Artist

Jess Harrison: You began the project for ‘New Nationalisms’ in 2009. What made you take up this subject matter at that time?

Tomáš Rafa: In 2009 a local municipality in Michalovce, a small town in eastern Slovakia, decided to build the first segregation wall which would stand between the town and the Romani settlement at the boundary, cutting off the majority from the Romani minority. The local municipality legalized this segregation wall by claiming it was a “wall for sport purposes” and built it using public money. I was a student of Fine Art at the University at the time and decided to organize a football match with kids from the Romani settlement because I felt I had to react to the situation. From this I created a short one-minute video and that was the beginning of my archive.

JH: Are these “Walls of Sport” still standing or being built?

TR: Yes, they are still in public space. One group of activists tried to destroy the wall in Košice but they only managed to destroy part of it and the next day it was repaired. In my opinion, none of the walls should be legal buildings. Local municipalities decide they wanted them so they are built, but there is a process of regulation which is being ignored. In Košice, another city in eastern Slovakia, it was particularly ironic because the walls were being built in 2013 when the city was named the European Capital of Culture.

Tomáš Rafa: ‘Wall of Sports project, painting workshop for kids in Romani settlements, Slovakia,’ 2014 // Courtesy of the Artist

JH: In the years since you started filming would you say that there’s been an increase in the legitimacy of ultra-nationalism in the political establishments of the countries which your work focuses on?

TR: Yes, and it is still increasing. I started filming during a time when these far-right groups were at the boundary of interest and were a small community. Over the years I have definitely witnessed an increase in their influence in public space; their protests have become more and more powerful and are attended by more and more people. I have also noticed a rise in the levels of violence: In Slovakia and Czech Republic this is more focused against Roma people and immigrants, whereas in Poland and Hungary, for example, it is against immigrants and the Jews. A lot of these groups are now active from within the political establishment and in parliaments as their own political parties.

Tomáš Rafa: ‘March of nationalists and members of ONR in Warsaw, Poland,’ 2017 // Courtesy of the Artist

JH: Your filming style is characterised by how deeply embedded you become in each scene, you are a participant in the action. How do you act when you are filming the alt-right groups, and how do those you are filming respond to your presence?

TR: It initially appears like a dangerous thing to do but I have a lot of experience so in most situations I know how to act. The most important thing is to act like you belong in the environment and to keep calm. Usually I resist discussions with these groups and if there is any aggression I avoid discussion completely. If I record statements it is because they want it. I never ask them questions.

Tomáš Rafa: ‘March of ONR to commemorate nationalist movement’s foundation 83 years ago, Warsaw, Poland,’ 2017 // Courtesy of the Artist

JH: In what ways do you think the alt-right relies on the media and social media?

TR: These groups need all kinds of propaganda including videos, media and text to support their activities and disperse their ideas. They often use “fake news” and involve themselves in “hoaxes” to do this and there are a lot of online portals and servers used to generate these. You find a lot of strange Facebook pages that spread propaganda against the Romani and against the Jews to get more members. I think the use of social media and online portals to generate this false information attacks normal kinds of information, but obviously it works for their purposes.

They have even used material from my YouTube channel. They download and use it illegally to generate their fake news. There was one 40-minute film uploaded onto YouTube with 10 million views, which I checked the content of because I was pretty sure there was something from my account and I found three seconds of my footage in this video. I flagged it to YouTube so they deleted it but unfortunately there were dozens of fake accounts which had already uploaded it again. It’s impossible to beat these groups because they have a lot of members who know how to use social media. One person against them—that person is not going to win.

JH: I was interested by the notion of uniform and costume when watching your videos of these protests, as so many members of far-right groups dress the same.

TR: By dressing similarly, they adopt costumes that work as a form of group hierarchy and give them structure. One group, the Kotleba/People’s Party Our Slovakia, used uniforms very similar to that of the Slovak Republic, a territory controlled by Hitler, until 2008. They organised marches with flares like soldiers. In 2009 there was a big change, however, and they started wearing green t-shirts with a white double cross that was used in the Second World War by the Slovak fascist army.

It is very popular in Eastern Europe to dress in t-shirts and jackets with patriotic and far right symbols on them. Everything has a patriotic theme. Balaclavas are not as popular at the moment because the there is no need to for them to hide their faces when they announce their statements in public space against Jews or immigrants or Romani people. They don’t need a disguise; they simply all look the same and are given a structure to be able to attack those they deem to be foreign people on the street.

JH: It was also interesting the way people treated flags in the footage. There are many shots of people burning the EU flag and protecting their own nation’s flag. Why do you think it’s so hard for people to identify themselves as being European?

TR: Increasingly it is people from the younger generation who are joining the alt-right groups and expressing their nationalistic and anti-EU sentiments. This young generation does not know what it means to be alone, to not be able to go outside of your country and to only be allowed to do what the party decides. They have no experience of idiosyncratic or authoritarian regimes and so they don’t appreciate the value of democratic structures.

Tomáš Rafa: ‘Wall of Sports project, painting Roma flag on segregation wall in Velka Ida, Slovakia,’ 2013 // Courtesy of the Artist

JH: Is your project for ‘New Nationalisms’ ongoing?

TR: Yes, it’s still ongoing. After 70 years, once again far-right groups are uniting against the Jews and Roma people which is unbelievable. It seems as if we are stuck in this repeating cycle. The difference this time is that the Jewish community is such a minority in Eastern Europe compared to before the Second World War, but the hate speech remains the same.

Exhibition Info

KUNSTHALLE BRATISLAVA

Tomáš Rafa: ‘Paradox of Tolerance’

Exhibition: Feb. 16 – Apr. 15, 2018

Námestie SNP 12, Bratislava, Slovakia, click here for map