Article by Karina Griffith in Berlin // Wednesday, Mar. 7, 2018

One of the highlights of the Panorama program at this year’s Berlinale Film Festival, Leilah Weinraub‘s ‘Shakedown’ is an intimate portrayal of south central Los Angeles’s Black queer erotic dance scene. The first character we see is Weinraub herself, setting up the camera as she speaks to Egypt, a club patron who also became a dancer. Weinraub gives instructions to Egypt, explaining that the text she wants her to read will be “like a voiceover.” With more than 400 hours of material shot between 2002 and 2004 and edited over the span of 15 years, ‘Shakedown’ demonstrates remarkable care in articulating the power of the director to create a representation. Weinraub constantly translates the conventions of the documentary genre to both the protagonists and the audience through voiceovers, like Egypt’s, and her subtly exhortative storytelling style.

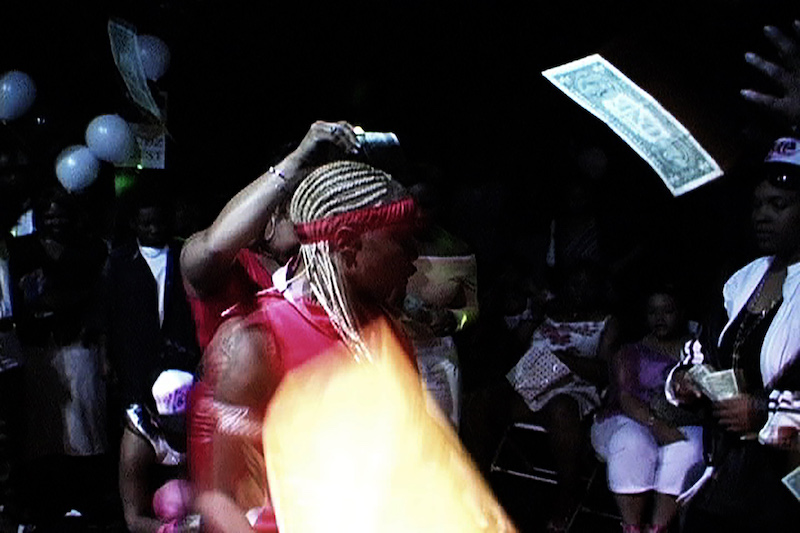

‘Shakedown’, 2018, film still // Photo © Memory

When filming wrapped, Weinraub moved to New York to study. In that time, she co-founded luxury brand Hood By Air with Shayne Oliver, yet she never lost sight of the film project. After turning down opportunities to cash-out on the project, by turning it into a television show for example, ‘Shakedown’ in its final form feels like an intimate family portrait. Weinraub’s talent is her ability to weave between allowing the audience to forget about the camera and then forcing viewers at opportune moments to become aware that they are, in fact, watching something. She is acutely aware of the power of spectatorship and the film is a subtle study on the economy of the gaze. What the audience experiences is a filmmaker questioning and queering conventions of cinema in partnership with her protagonists.

Visually, Weinraub also pokes fun at conventions. A lasting shot of digital black is held just long enough for the audience to make out all of the other colours in the pixilation—the green, yellow and blue squares that collaborate before our eyes to render the image of night. Nothing is opaque in ‘Shakedown’: The story, the protagonists’ telling of it, and what Weinraub chose to show are translucent; some details are illuminated but the beholder does not hold the object of her gaze.

We sat down with Weinraub to talk about genres and the language of documentary.

Karina Griffith: The film shows the world you created and your process—the behind the scenes of your behind-the-scenes experience of this space. How much of this transparency is a function of the topic of the film, and how much of it is your own commentary on the medium of film itself?

Leilah Weinraub: It’s both. When you make a decision over and over again, it becomes a theme. There were some original ideas that I had, or that I was taught, about film and cinema and media making. On one side, it was about “There is no such thing as objective documentary, it just doesn’t exist. It is a completely subjective process.” And on the other side it was about spectacle, but also about the truth behind the spectacle. I thought both ways of making film were extremely important. Over the years I had to find my own way, really be true to what my experience was and see what was happening in those interviews. You shoot so much stuff and everything that ends up in the film is imbued with all of this information. It is a collection of all those moments.

KG: It’s amazing because you started filming in 2002, so this is a span of at least three American presidents.

LW: That was really important to the story. When I originally started working on it, it made me think a lot about subculture. I would have to explain the project to people and they would say, “Okay it is about a ‘subculture,'” or “It’s ‘underground.'” I had to think about what “mainstream” culture was—what is the experience of mainstream culture? How do we experience it? Is it the news? Is it war? Is it the history of war? Is it pop music, is it Michael Jackson? We can’t say what our collective experience is; everything is really a subculture. Sometimes I think war is a mainstream experience and everything else is niche after that.

I started filming right after 9/11 when I moved back to LA. To me the whole world changed after 9/11 and now it’s in a completely different spot. So much has disappeared. It feels tight and closed.

KG: You start the film by showing the titles of the 22 chapters, the form that the film will take. It reminded me of a video game, as though you could watch it again and mix the chapters into a different order…

LW: It’s an experiential piece. There are a lot of different things you can grab onto to feel grounded. The film tells you how to watch it. There is a language for documentary and I was trying to take some and leave some. There were a lot of suggestions on how to make the film “film-world ready” and I tried them and they didn’t work. Those didn’t make it into the film.

Genres are really for commercialism. For example, there is the idea of folk music. Originally, folk was supposed to be from one person to another—one day you are performing and another day you are watching. That is folk music. Then it got turned into this genre of folk music to sell albums. ‘Shakedown’ is that experience of folk. It is your world, so you get to do what you want to do. That is Egypt’s story in the film. She went to the club, she thought it was cool, she loved the performances of the legends and she said, “I can do that.” And then she tore it.

‘Shakedown’, 2018, film still // Photo © Memory

KG: You seem really in tune to how the spectator is watching.

LW: The show literally is about that. The way the stage is at the club, it is the same level as the audience. It is interchangeable; you can be a patron and then become a performer. It is not an elevated stage. Everyone is on the same level.

KG: So when will we see you in Berlin again?

LW: I was asking myself, “Should I come here for the summer?” The rent is cheaper than New York, so that is a plus. America is very heavy right now and it sucks. When you come to Europe, you get off the plane and you are like, “Whew!” but then that wears off. When it does, it is even more depressing. I was thinking about living in Europe and I was thinking about living in Asia… It is an escape thing—how can I escape the tragedy of the world?

KG: You were invited to show an early version of ‘Shakedown’ at the 2017 Whitney Biennale. How did the reception in that space inform the work you put into completing this version?

LW: It made me think that there is huge space for film in the art world. People will not argue with your film. They will just receive it and watch it and listen and put a lot of energy into watching. I feel that the process of coming to the film world with it was like, “Take that out, don’t show that, label that.” I don’t believe that a bigger audience is a less intelligent audience. I think viewers are so smart. I don’t think there is an art audience. There is an audience that art institutions cater to. Film is an imagination space and that is what it is for. It is supposed to change the way you think, the way your mind works, the way you organize information.

KG: What sort of change do you hope happens with this film?

LW: The order of operations of how you process information, how you process information discerning truth. Fiction and documentary, it is insane that those are two different things; that people think they are acting when they are acting; that documentary is not acting; that a film crew when they are filming think that they themselves are not acting. The most fictional experience is a film crew. I think reportage and news media are different—that is not what I am talking about. I am talking about this longer time-based storytelling. Storytelling is how you learn how to live.