Article by Samuel Staples // July 10, 2018

What does it truly mean to immerse oneself? This is one of the many questions explored in the exhibition ‘Welt ohne Aussen. Immersive Spaces since the 1960s’ currently on view at Gropius Bau. The exhibition, curated by Thomas Oberender and Tino Sehgal, features work spanning from the late ’60s to the present by artists such as Larry Bell, Doug Wheeler and Cyprien Gaillard, among others, combining installation, 3D film and virtual reality with live performances and workshops. One of these works is Smeller 2.0 (2016), a smell organ created by Austrian-born Berlin-based artist Wolfgang Georgsdorf, in which viewers are exposed to a symphony of smell and intense multi-layered compositions of scents within an immersive chamber.

Lead into a dimly lit room, lit only by the luminous Smeller 2.0, viewers are encouraged to close their eyes and, should the scents become too intense, move to the sides or back of the room. Each scent is there only momentarily before dissipating completely. Grass and floral scents are followed by manure, soil, animals and fire—an evolution in 12 minutes. After viewing the installation, we sat down with the artist to speak about the project and learn how exactly it works.

Samuel Staples: What is your relationship to the medium of “smells”?

Wolfgang Georgsdorf: In one way or another, I have been working with smells for years. This interdisciplinary nature of my work has always been there—I always made music, drew, painted and made sculptures, and now I’m conducting the Berlin Improvisers Orchestra. There’s always a vivid connection between disciplines. Smell has been involved since my childhood; I grew up with my grandparents, my grandfather was a chemist and the elder sister of my mother was a chemist, so they had quite some medications at home and a lot to sort out regularly. I remember as a four-year-old asking them to not throw it away but to give it to me to play with and smell. That’s the true early legend of how it all began. Later I fried trouts while conducting Schubert’s Trout Quintet and we had performances where we threw fish into the audience. Smell was always so intriguing, the way it came and the way people have different thresholds of smell, of what is ugly and what is beautiful, different dislikes and preferences.

SS: This project is called Smeller 2.0. Why 2.0?

WG: In 1996 I built the first prototype of “Smeller,” the Smeller 1.0. It was a mechanically steerable and controllable prototype, like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. You had to turn levers to get the smells out. It had only 30 channels, not 64 like 2.0, and was used by the audience at the State Museum of Austria in Lindz for 12 weeks or more. People were almost crawling over it to use it, children especially.

That was also the first time that I had an exhibition that allowed me to gain sponsorship, and this project was always dependent on sponsorships. In 2012 we built Smeller 2.0, 16 years after the prototype. No one would invest in it—there was mild laughter, smiles, but no one would invest. At the time, the vision was almost 30 years old, the vision to have time-based art with smells.

SS: Could you describe the mechanics or inner workings of Smeller 2.0? How exactly does it work, and so well?

WG: It’s crucial to have an artificial situation to have distinct smells that are not blurring or unintentionally lingering, and to compose with them as we do with tones in music, which is also an artificial situation, as is what we do with pictures in film. For these collective experiences you sit in a room and do nothing but sit and breathe. That’s what you do when you’re at a concert, a cinema, the theatre: You don’t move but the people move, the tones move, the lights move. I wanted to have that same situation and meet the other disciplines at eye level with our sense of olfaction.

When you have a computer with 64 channels you have all sorts of possibilities to combine and juxtapose these channels and layers, so we had to find a way to separate these smells in order to have a new smell with every breath we take. What makes it possible, what makes it work so well, is a very sophisticated confluence and combination of various different airstreams. The study of air was the basis and crucial to the technical success of the invention. Air is chaotic air does what it wants.

It was a question of modifying the whole space, as it’s a spatial installation. It’s easy to blow smells into a room but it’s very difficult to get them out. It’s easy to mix up smells but it’s very difficult to separate them afterwards. It was a long chain of trial and error, and it was a really substantial schooling in frustration tolerance to get where we are now.

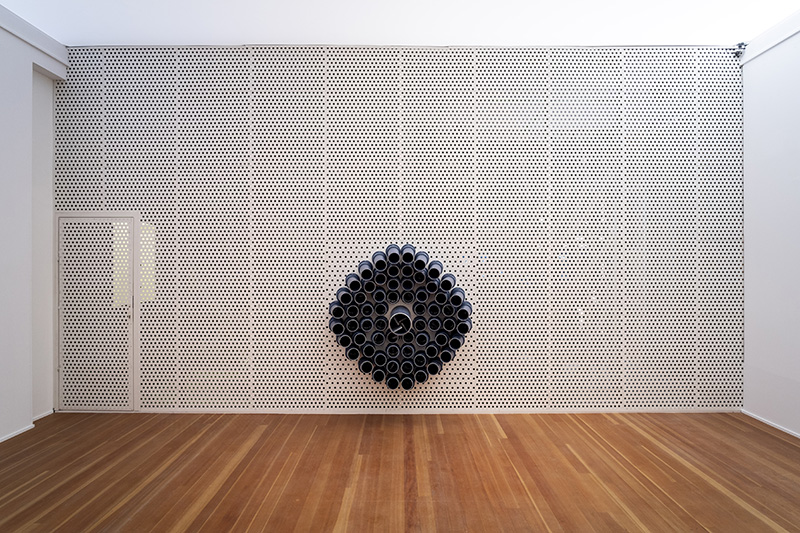

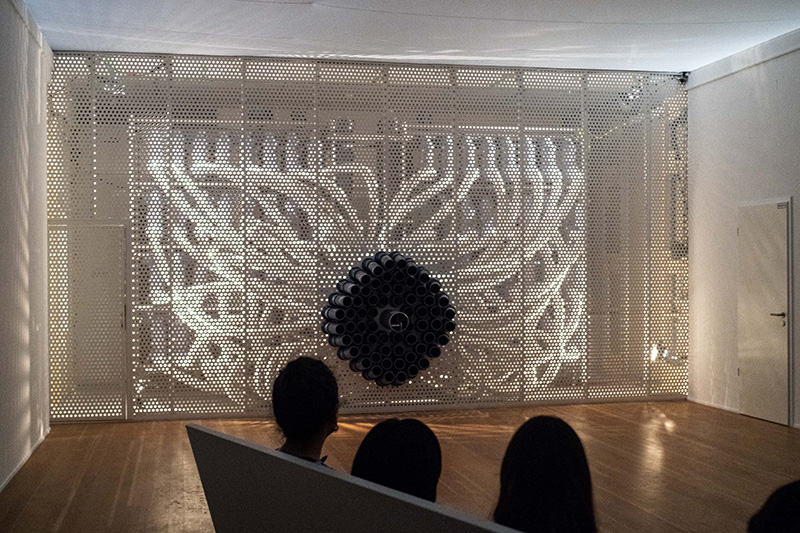

Wolfgang Georgsdorf: Smeller 2.0, 2016, installation shot // Courtesy of Gropius Bau and the artist, photo by Mathias Voelzke

SS: Smeller is now being researched scientifically by the Interdisciplinary Centre for Smell and Taste at the Dresden University Hospital. I’m interested in this intersection between art and science—how did this come about and what have been some of the initial findings?

WG: I have been lecturing at the International Centre for Smell and Taste at the University of Dresden Hospital since 2016. Empirically, they found out with their own studies that ‘Smeller’ and ‘Osmodrama’ are capable of helping depressed and depressive people, but to gain a certain recognition in the scientific community, empirical studies are not enough. What is happening now is an evidence-based, controlled study. The study will be conducted in three consecutive sessions every day until the end of the exhibition. I don’t want to anticipate the result of the study, however, we do know that it works. The way and to what extent it works and why it works will be subject of the publication that follows.

SS: Can you explain how it works in helping people in this way?

WG: It works because of its revitalization of someone’s emotional life on a subconscious and conscious level. Our old brain hosts and processes emotions, memories and pictures as well as smells. The old brain is part of our brain from the very beginning, it is the first thing that develops in the fetus from the first cell that divides in the womb. In this way, there’s no reason or judgement involved when you smell; you can only have a reaction or a reflex—fight or flight, mate, eat, play. How far it works, how well it works, how long it works and how much exposure you need are things that we still need to find out.

One of the most wildly spread forms of depression leads to an anosmia over time, a blindness of the nose. They have already found that if depressed people or anosmic people are exposed to a high frequency of smells, then over time they show improvement and less symptoms. The anosmic people got their sense of smell back because it was addressed all the time.

Wolfgang Georgsdorf: Smeller 2.0, 2016, installation shot // Courtesy of Gropius Bau and the artist, photo by Mathias Voelzke

SS: The project is very much centered around olfactory memory and how certain scents can trigger memories and emotions amongst viewers. How did you become interested in this idea and in the possibilities to explore these concepts through your art?

WG: There is a white stain on the map of the history of art. In other words, it interests me because there is nothing. It was a big draw to go where no one had ever gone before and to find a new perspective or new land in the chasm and to extend the thinkable world. We are in another dimension now and there is a new form of art, which is the art of time-based composing and performing with thousands of scents and smells. The impact of this we do not yet know, but I strongly believe there are intersections that can be made with theatre, film, dance and music. I’m doing this because I’m totally intrigued, obsessed and fascinated by the fact that I’m finding a way to paint pictures behind the eyes instead of in front of the eyes. The intersection of visibility and invisibility is where imagination replaces a real object, and the picture comes from behind your eyes. That happens with music, with literature and with smell.

Exhibition Info

GROPIUS BAU

Group Show: ‘Welt ohne Außen. Immersive Spaces since the 1960s’

Exhibition: June 8 – Aug. 5, 2018

Niederkirchnerstraße 7, 10963 Berlin, click here for map