Interview by Brit Seaton // Oct. 09, 2018

Most of us probably haven’t asked our neighbour for a cup of sugar, let alone asked them what they’d do with a cash sum of £100. In September 2017, the latter request floated through the letterboxes of one thousand households in the Greater Manchester borough of Trafford, delivered by Gideon Vass—a local artist who acquired Arts Council funding through this proposal. A year after the project’s inception and the £100 Idea has seen Vass select and fund the suggestions of ten participants, including the construction of a wooden boat to be rowed down a canal, the purchase of some pet fish and a tank, and an offer to share the money out between family.

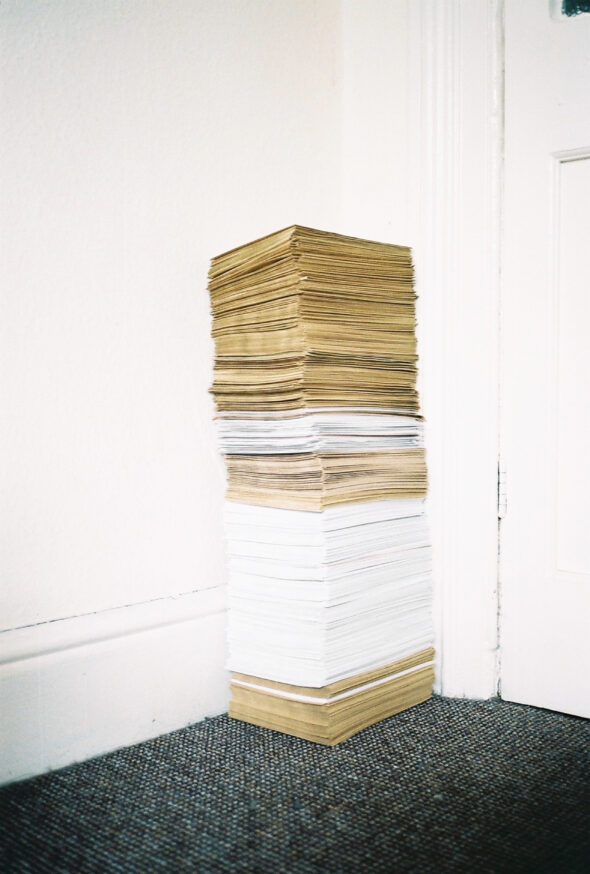

Gideon Vass: ‘Stack of Letters’, 2017, Old Trafford, Greater Manchester // Photo by Gideon Vass

The £100 Idea presents an instance of socially-engaged art practice, made possible through the willing participation of the public, while maintaining the artist’s characteristic focus on his immediate surroundings. Vass embraces the ironic guise of a gimmicky title: beginning the conversation with the open offer of funding, the project has initiated new social relations within the community, developing through the varying degrees of time and attention necessary for each idea’s realisation. At a point in which the projects have reached a level of completion or continue as ongoing entities in the participants’ lives, we spoke to Vass about the potential of art as a form of care and the significance of socially-engaged practice in the community.

Brit Seaton: Your work often identifies a distinct ‘territory’ as a point of departure or focus, like a dependent variable in an experiment. Can you tell me about your use of money as a foreign territory in the £100 Idea, and how it distinguishes the project from your previous work?

Gideon Vass: The £100 Idea came in response to an open call brief that was offering £5000 to three award winners, to produce their proposed projects. Having not used money for a project before and struggling to increase the production value of an existing idea, I decided to turn my attention towards the money itself. I wanted to see how people would respond to the offer of money, so I determined an open call system that found members of the public by chance.

Brit Seaton: Tell me about the character of the participants’ ideas, many of which incorporated opportunities to care for themselves or others in the community. Did this element play a role when selecting the ten households to participate?

Gideon Vass: In the respondents who were selected, I perceived an openness and honesty—something that spoke about their willingness to participate. After meeting the participants for the first time, I quickly learned how significant the timing of the letter was for a few people. Amanda found out she had secondary cancer the week she received the letter; Angela awoke to find her car severely damaged by a joyriding accident just days before; and Maria was in the midst of moving to Guildford, Surrey. The households received the letter from a stranger, having every right to be skeptical and doubt the legitimacy of the offer. This process singled out the respondents who had to put trust in, and open up to, the stranger.

Replying to the letter was a chance for people to reflect. Care characterised many responses because care characterises many people’s lives. By responding, they too were caring for me, the artist, who relied on their responses to fulfil the project.

Gideon Vass: ‘Kymani and Mikhkil feeding their fish’, 2018, Old Trafford, Trafford // Photo by Gideon Vass

Brit Seaton: Since the beginning of the project, the collaboration between you and the local households of Trafford has initiated new friendships in your community. From this experience, how do you reflect on the role of art as a facilitator of such relations?

Gideon Vass: The £100 Idea is a public, participatory project, a sociological project. Art is a product of the project and a subject discussed during the project, but I wouldn’t say art was the facilitator. I think it’s a good thing that art doesn’t have an assigned role; it makes it a great tool to ask questions. By addressing the complex topic of money under the umbrella of an ‘art project’, it allowed the research/experiment/project a certain freedom.

It’s hard to talk about what art does and doesn’t do when you’re not particularly sure what it takes credit for. I suppose it doesn’t matter. If you have ever tried booking a village hall or community space you will soon realise the sheer volume of social activities going on—the village hall near me asks for bookings five months in advance to secure a space. There seems to be infinite ideas and activities that facilitate such relations. I don’t think art is particularly special in that sense. The spirituality and togetherness facilitated by a boxing coach at the local village hall won’t receive widespread recognition, that’s not its purpose. But art, it wants to be recognised, wants to be read about—often making something slight seem significant. Spokespeople can often make judgments about places they know little about. Art shouldn’t make that mistake. It should talk to the people before it starts speaking for them. I think any social project done thoroughly and properly, be it art or not, will facilitate such relations.

Gideon Vass: ‘Matt’s boat: initial float test’, 2018, Stretford, Trafford // Photo by Gideon Vass

Brit Seaton: You explain that after the money had been delivered, there was no assertion of time pressure or actual obligation for the participants to realise their project. In some instances, the actual use of the money differed from the initial proposal. How did you navigate your expectations for the outcome of the project, particularly in terms of fulfilling your own Arts Council funding proposal?

Gideon Vass: I must make it clear that this project exceeded my expectations the moment I had received all the responses. I came into the project without any knowledge of what was to come. I was as much a participant as the households. Imposing a prescribed deadline to buy a fish tank, to give £100 to a neighbour or to build a boat would be to limit the project’s potential. It was a project to be experienced—not rushed—so I allowed things to develop naturally, becoming close friends with some of my collaborators.

One of the participants lost their job due to illness and used the £100 to buy food instead of their proposed idea. The £100 was always the participant’s money to use how they wanted. Throughout the project, I worked with each household to build an archive of documentation, objects and writing that tells the story of their journey through the project. The prospect of being a part of an eventual exhibition was exciting for certain participants and so it was important to have a physical archive that reflected the ideas, the journeys and the relationships.

Gideon Vass: ‘Grand opening of Amanda’s new front door’, 2017, Sale, Trafford // Photo by Gideon Vass

BS: Particularly with the context of austerity in the UK, has the project influenced your perspective on the social responsibility of contemporary art?

Gideon Vass: Responsibility stems from the top, and I feel most major contemporary art institutions talk about social change but don’t do enough about it. A direct lesson from the £100 Idea is that opportunity is the most important thing. Let’s say a major Manchester art institution put together an open call for 15 local artists to propose a project of positive social change, all funded £1000 to fulfil the project, with emphasis on a public outcome. That’s a lot of local artists doing a lot of good work for the people and for art. If that was mirrored in Liverpool and Leeds, that’s 45 projects, varying in scale and direction, all happening at one time. This could be an annual cycle. That is a magnificent amount of energy and momentum going into social change through alternative thinking. This is just an idea, but ideas are what is needed. People have got an awful lot to give, if given the opportunity to do so.

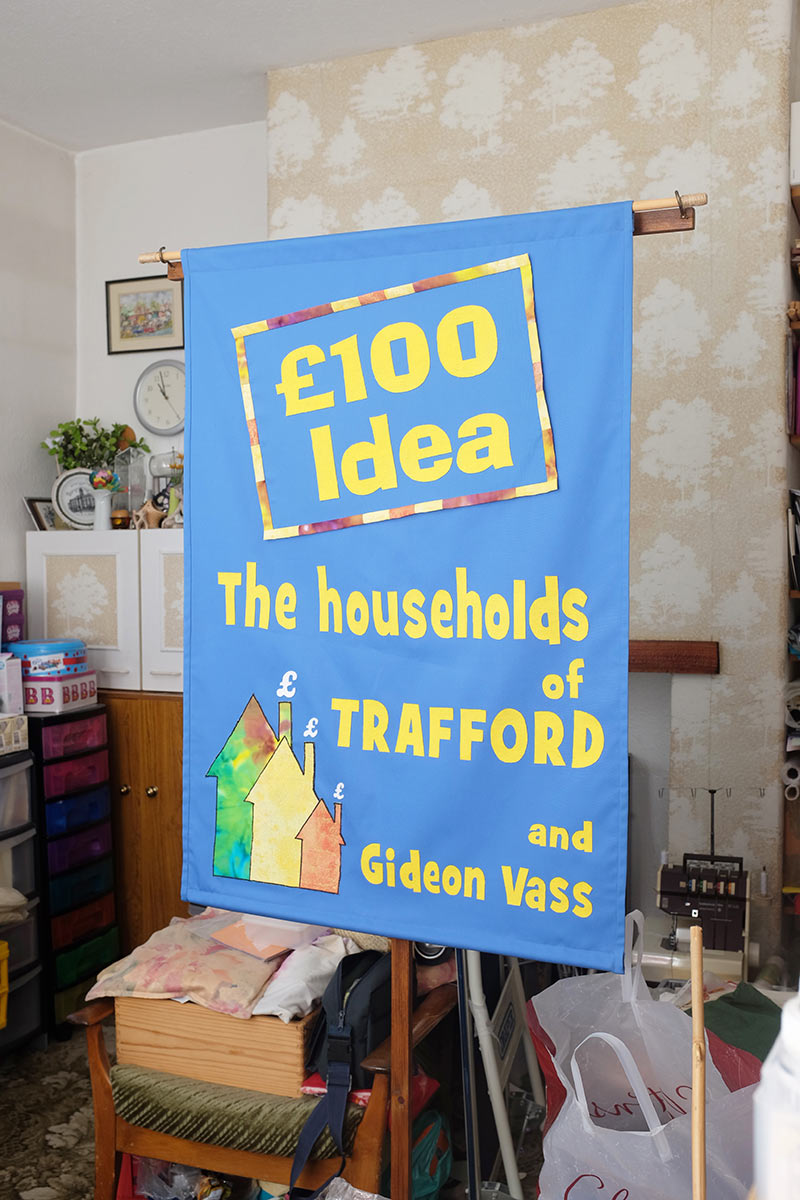

Gideon Vass: ‘Janet’s banner in her front room’, 2018, Sale, Trafford // Photo by Gideon Vass

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Care’. To read more from this topic, click here.