Interview by Benjamin Busch // Dec. 21, 2018

Sergio Zevallos, born in Lima in 1962, is a Peruvian-German artist whose work, beginning in the early ’80s, has spanned performance, installation, drawing and photography. From 1982 to 1994, he was a member of the Grupo Chaclacayo, known for its performances positioned against the sexual and racial violence surrounding Peru’s armed conflicts. Zevallos’s work is iconoclastic, tearing down epistemological regimes inextricably tied to colonialism. Last year, he took part in documenta 14 and has recently been named the winner of the 2018 HAP-Grieshaber-Preis der VG Bild-Kunst, awarded by Stiftung Kunstfonds. His current exhibition in Berlin, envisioned as a site-specific composition, features a selection of graphic works from the ’80s and today.

Sergio Zevallos, ‘New Journey to the Equinoctial Regions’, installation view, 2018 // © Photo: Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin, 2018

Benjamin Busch: The title of your current exhibition, ‘New Journey to the Equinoctial Regions,’ comes from Alexander von Humboldt. What significance does Humboldt have for you?

SZ: Humboldt spent an important part of his travels in today’s South America, including Peru. There are several levels of relationships between my biography as a cultural producer, and Humboldt’s history as a cultural producer. I’m also traveling a lot back and forth between Latin America and Europe.

Which kind of ideologies and information and products are we transferring between both parts of the world in all these travels? What is the function of what we are bringing? In which context will it be read? What is the role of that as political knowledge? Or, in the end, what is your function as a person in today’s life?

Humboldt is, in Germany, considered a kind of hero of the new humanist development of civilization: open minded, against slavery, etc. I and several colleagues in art and other fields of research see it the opposite way. Humboldt was part of the developing of the colonial relationship and was at the starting point where the old traditional colonial relationships transformed into the new capitalist, colonial relationship.

While he was there, Latin America was still administrated by the Spanish Kingdom. A few years later, all the wars started. Several of these wars against the Spanish administration were supported by other European countries, mostly France and England. These other countries invested in the wars against the Spanish administration to have access to all the riches and resources.

Humboldt’s so-called “scientific description” started a new fantasy about Latin American and South American theological spaces, telling of amazing natural landscapes with incredible plants, a lot of metals and very exotic animals, a few of them even human animals. After Humboldt, a new series of travellers, who were not so interested in nature, but rather in resources, went there. It’s a line without a cut. It is a line developing in several steps towards the transformation from the old style of colonialism into capitalist colonialism.

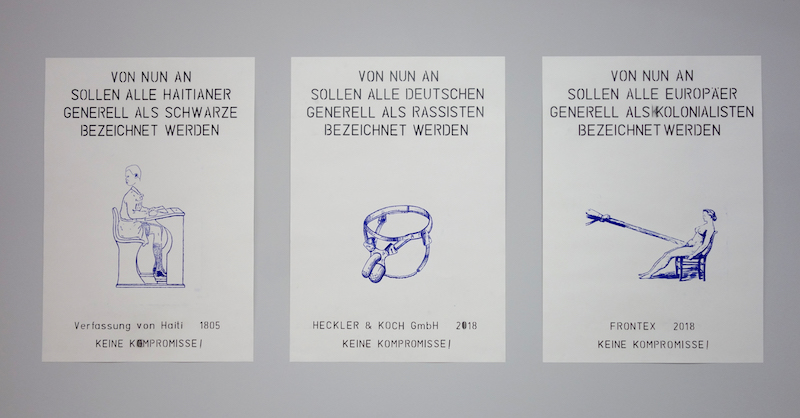

Sergio Zevallos: ‘Haiti’, 2018 // © Photo: Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin 2018

BB: In your work Haiti, the Haitian Revolution and Frontex are presented in the same line. Is this the line you are talking about?

SZ: I’m presenting the first three works of maybe 10, 12 or 15 variations on this sentence from the Constitution of Haiti, 1805. [“The Haytians shall hence forward be known only by the generic appellation of Blacks.”] For me, that is one of the most powerful sentences. It’s so current. It’s like a grammatical deconstruction of any kind of relation we used to have with the concept of racism. It transforms everything.

To approach this sentence from the 19th century today, I started to write these variations. I had to find another interlocutor with this sentence. Its original interlocutor is the people who invented or developed this concept in the Constitution of Haiti. In the other variations, I’m trying to find several current institutions in power, who are the result of all these developments of colonization.

The first two institutions I chose were Frontex, an institution charged by the European Community to control its borders, and Heckler & Koch, the producer of the HK G3, one of the most famous weapons distributed all over the world: used by the army in Peru, the drug dealers and cartels, everyone has these weapons that are produced in Germany by Heckler & Koch.

The point of this series is that racism isn’t limited only to perception and the feelings that it evokes, by the meeting of people of so-called different races. For me, racism is a complex which is, from the beginning, an economic relationship. You cannot separate the experience, the feeling and the ideology of racism from the economic power relationship that it comes from, and which is maintained today.

We have a world separated into geographical areas of high privilege and areas of low or even no privilege. Everyone, including myself – I have a German passport, I am included in the sentence when I say, “From now every German shall be called a racist.” We all who are living and having access to all these privileges as a part of this historical complex are in a way racist, because we can only keep having these privileges by being inside and supporting this structure.

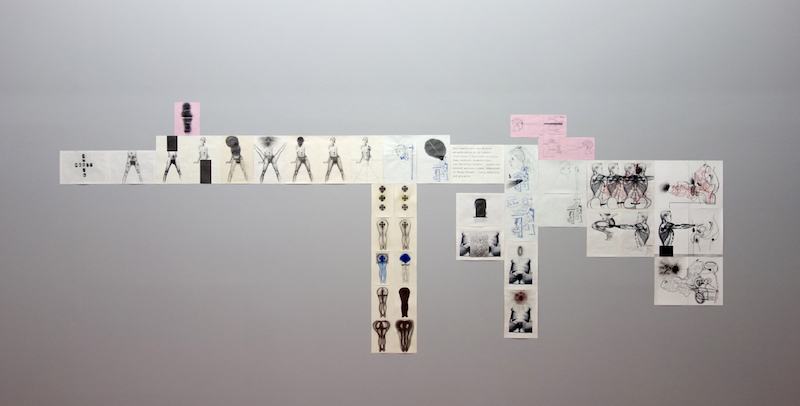

Sergio Zevallos, ‘HK G3’, 2018 // © Photo: Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin 2018

BB: Your work suggests a discourse between where images are produced and where they are presented. In HK G3 you use notebooks, or pieces of notebooks, and the technique of drawing, to combine images from sexual education, ethnography, forensics and the floor plan of a bank. How does this distinction between field and forum, lived space and representations of space, inform your work?

SZ: Humboldt’s ‘Journey to the Equinoctial Regions’ is a compilation of descriptions, of texts and drawings. I called my exhibition ‘New Journey to the Equinoctial Regions’, making an analogy to this practice. Same as Humboldt, what is not present in a direct form is the life, the real existence of people, but instead we see their representations. Humboldt creates representations filtered not only by his ideology but also by his relationship with the Spanish administration. He could only travel using the ways of the colonial administration.

Further, he did a lot of interviews with the so-called intelligentsia: scientists, researchers, mestizos and criollos researchers in Mexico and Ecuador and in Peru. That means he also takes representations of these people into his work and brings them to Europe. There are several steps of representations until you get the final product, which is a completely different thing, more according to the needs of the European continent looking for all these resources. A lot of things just disappear.

I have always been using quotations in my work. Not only in drawings, also in performances. I take quotations from texts or pictures that are in my surrounding. There are a lot of quotations from things that I hate or disagree with completely, but I am still influenced by them in developing a position against them. There are a lot of quotations from things I appreciate.

This context of cultural production, in picture and text, is always in my work. The latest series, HK G3 and Haiti are completely built from quotations. In the case of HK G3, I decided to use most of the quotations from around the time of Humboldt. So, picture products of the 19th century, texts also. I take them and start to combine and play with them in the architectural space of the weapon. The whole composition is built as the architecture of a weapon. I use the quotation and play inside this space and find new relationships, combinations, symbioses, destructions, whatever. To do it that way is at the same time research, but also a transformation of myself. The intention of this is to make an intervention into today’s ways of thinking.

Sergio Zevallos, ‘Rosas’, 1982 // © Photo: Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin 2018

BB: In the exhibition, you show works from the ‘Rosas’ series, which you produced during a period of armed conflict in the ’80s in Peru. The series includes quotations, as well as imagery that mixes death with sexuality. What do these works convey? Considering the present political situation—in Peru, in Germany, and in the world—what’s your current outlook?

SZ: When I made the ‘Rosas’ series, my perception of reality, and my intention, was focused on the patriarchal male mentality that structures violence and colonialism. I decided to explore the ways of travestying, transforming, deforming, creating scenes of pleasure or suffering, between male bodies, around male bodies, into male bodies, etc., working with the concept of male as a material, which has to be analyzed in detail and taken through different transformations to understand how it can be liberated from its ideological structures.

That is a starting point of the very strong sexualization of the pictures from that time, and why these sexual representations are completely mixed, hybrid, androgynous – a political relationship between my so-called biological male body and the social-political male body itself. My series ‘Rosas’ was, at that time in the ‘80s in Peru, very provocative. It was a direct confrontation with the audience. But I find the series Rosas, in its deep statement, more current today, talking more specifically to what we are becoming now, the situation we are entering today.

In order to talk about male monster energy, it uses the myth of a non-sexual female body. This strange creature is the equivalent of what Europeans in the 15th and 16th century were telling about the strange spaces in the South American area: monsters with two heads, a mix between humans and animals, and all the discourse about cannibalism. Catholicism created, after this, many strange monsters. The invention of a saint is equivalent to the creation of a monster creature. It’s a body, which is non-sexual, but procreating.

I think that today, we are, in a kind of high-rationalist way, completely devoted to saints. This increase of fundamentalism is on all levels, not only on the confrontational level between state administrations. It is in our everyday life, where we experience more and more fundamentalist energy in our relationships. There is a parallel between the disposition to act or react in a fundamentalist way and the idea of super heroes—supermen, supergirls, supersaints.

Exhibition Info

DEUTSCHER KUENSTLERBUND E.V.

Sergio Zevallos: ‘New Journey to the Equinoctial Regions’

Exhibition: Dec. 07, 2018–Feb. 15, 2019

Markgrafenstraße 67, 10969 Berlin, click here for map