Article by Jesse Cumming, studio photos by Ériver Hijano // Feb. 22, 2019

Helga Fanderl’s ‘Raum für Film’ can be found behind an inconspicuous frosted glass window-front in Charlottenburg. The three words are visible on the window’s exterior, but they are easy to miss unless one is actively looking. It’s only the first confluence between the space and the work of the artist, who has been steadily producing and exhibiting small-gauge films that reflect fragments of life since the mid-1980s.

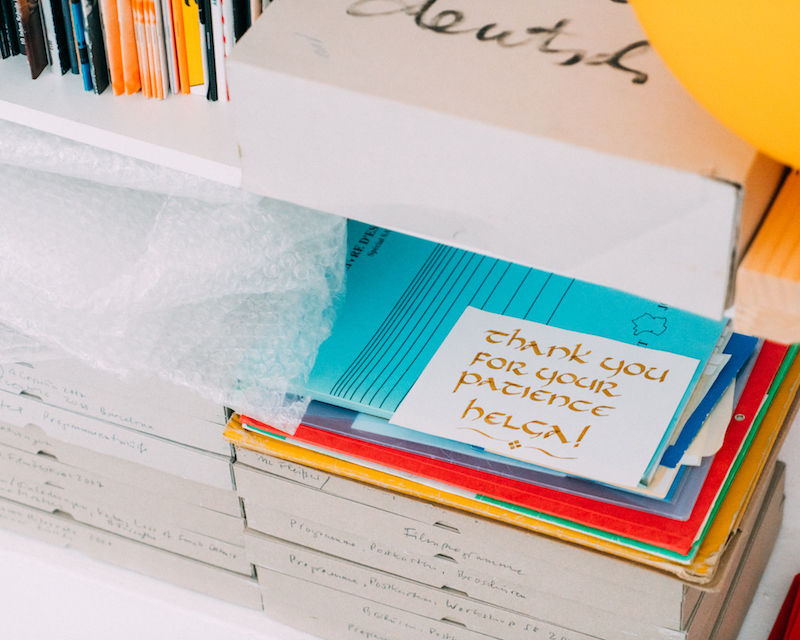

The Raum is her workspace; with its open main area and high ceiling, it resembles a literal white cube. Along one wall runs a waist-high shelf constructed to hold the majority of the room’s contents: photos, projectors, tools and many, many rolls of film, stacked neatly in silver and gold tins. “There’s always this potential to see them without seeing them,” says Fanderl, describing the arrangement, “and you can see them only when I run the projector.” Which she does, shortly after.

Born in Ingolstadt in 1947, prior to her career as a film artist Fanderl lived and worked in Frankfurt as a professor of literature. With a practice that moves between the worlds of film and art, Fanderl’s work has been recognized by both, earning the Coutts Contemporary Art Award in 1992 and the German Film Critics Association Prize for Experimental Film in 1998.

The bulk of Fanderl’s practice happens outside of her studio space. Her chosen medium is Super 8mm, which she shoots independently or, to use a term that she returns to, “freely.” Most often, she turns her camera on the world, capturing brief and poetic glimpses of nature, objects, spaces and people. Her films are entirely edited in camera, with the refined work guided by her eye, her training and her response to a particular site or subject. “I lose my mind when I film,” she tells me, “and I love this state, being really at unity with what I’m filming and not with an idea of how to make a film.” There is a certain grace and purity in the formal simplicity of the work, something mirrored in her studio. “It’s really a wonderful space,” she says about her surroundings, while also, inadvertently, describing the experience of being immersed in her first-person films. “It’s intimate.”

As her work requires no post-production, the Raum für Film is where Fanderl self-curates her finished miniatures into small assemblages, with her reels usually totalling between two and seven titles. For solo programs of her work Fanderl assembles arrangements that typically run between fifty and sixty minutes. Occasionally, the individual reels consist of recent works, while they can also incorporate selections from Fanderl’s extensive archive. The groupings can be guided by the choice of colour or black and white, the different rhythms of the films, their individual subject matter or other ineffable connections.

The longest of her films run 3 minutes and 25 seconds, the duration of a single 8mm film reel projected at the “silent speed” of 18 frames-per-second, rather than the standard 24. The reduced frame rate lends the already poetic fragments a dreamy rhythm. “They’re like drawings,” says Fanderl of her work, “they’re not like big paintings.” She notes her fondness of sketches by great artists, and her original passion for visual arts more generally. “I’ve always loved painting and drawing, and I loved it for a long time before I knew about experimental cinema.”

With titles that could very well be borrowed from 19th century Romantic paintings—like Clouds Between Buildings, Gare de l’Est, Stone Bridge and October Trees—Fanderl’s films are named with a simplicity and straightforwardness that extends from the work itself. Like the sketch work she admires so much, her own films exist as deceptively rich gems, cinematic distillations that effortlessly wed artistic skill with conceptual simplicity.

She begins her process of self-curation by writing and reflecting. “In the end, it’s like a poem, where I have only the titles,” she says, noting that while certain of her films are digitized, several are not, and each time she chooses to project a print there is a risk of damage. While the programs she ultimately assembles remain mutable, Fanderl frequently declares an arrangement complete, then producing a 16mm blow-up.

She pauses when asked about how many films she’s made. “In 2014, it was about 1000, and since then I haven’t counted,” she eventually responds, before quickly adding, “It was only for the catalogue raisonné. I don’t want to speak too much about the number, because the number is not the important thing.” She emphasizes: “the process is what’s important.”

As a filmmaker who works in small-gauge formats, she also prefers to present her work on smaller scales, at times even making efforts to adapt spaces to better suit her work. At a 2018 screening and lecture at Berlin’s Kino Arsenal, Fanderl installed her Super8 projector in the centre of the room and chose to forego the main cinema screen in favour of a smaller, portable alternative.

She describes her Raum as “semi-public”, and as an extension of her programming she occasionally transforms the space into a makeshift cinema to host presentations of her work. “When I inaugurated it, I hosted three public evenings for people I knew, with three different programs, and after I invited them to have a drink,” she recounts. “It was really lovely.”

It’s something she’s able to do in the daytime, as well, and before long Fanderl lowered the automatic grate that covered the Raum’s windows. The space is plunged into a momentary darkness before Fanderl’s small yet powerful projector begins to whir, and the white wall opposite her shelves becomes a screen.

For an audience of two, she has selected a reel comprised of five films, each filmed last year in Paris, the city Fanderl called home for twelve years before moving to Berlin in 2016. She introduces the screening by reading the titles, which do resemble poetry in their cadence and evocative brevity: Mirrored, Flowering Tree, School of Beekeepers, Plein-Air Photos, and Mimosas in the Wind.

The first film is shot entirely in the water of the Paris canal, with images of people and buildings reflected upside down. They undulate and shift, with a dynamism aided by Fanderl’s fragmentary in-camera edits and movement, which constantly reframe figures or reorient itself to capture abstract plays of light on the water’s surface. The subsequent four parts of the program are filmed in the city’s Jardin des Plantes, some a joyful glimpse of park-goers in the sun, others more contained observations of trees and flowers nodding in the wind.

Alongside the commitment to small-gauge celluloid and silent speed projection, Fanderl’s films are always presented silently. Of course, when seen in an intimate space such as this, the steady bustle of the projector’s gears becomes a natural sonic companion, pushing forward until the final film frames run through the machine and Fanderl switches it off.

The sound we’ve heard and the images we’ve seen seem to hang in the space, and stay with us as we exit the Raum back out into the city. The street is essentially the same as before, but after seeing the world through Fanderl’s eyes and camera one feels slightly more attuned to the surroundings: to the colour of a passerby’s scarf, to the quality of light in the air or to the texture of a building façade. As an artist who routinely invites the beauty of the world into her own private space, it’s only appropriate that her final works return the gesture, a generous exchange that we as viewers have the opportunity to observe and take part in.