Article by Sarah Messerschmidt // Mar. 13, 2019

Stephanie Hier often refers to the adage “falling down a rabbit hole” to describe lapses of time spent trawling the internet. The phrase, seemingly off-the-cuff, also describes her own work as a painter, which whimsically reflects on contemporary visual culture and the consumption of digital images. As a young artist, Hier has already developed a distinct painterly style, merging the forms of canonical art history with the more workaday icons of blithe mid-century cartoons. She is known to paste temporary tattoos over meticulously rendered still lifes; to frame complex realist pictures within less refined pictorial borders; to depict doe eyed cartoon animals and a troupe of grinning painters alongside glisteningly palpable fruits and foliage (as though it were the cartoons responsible for such adroit work and not she). She is a liberal user of colours, forms and media, drawing from a seemingly miscellaneous inventory of sources, in effect collapsing the boundaries between high and low art to evince the “flatness of possibility” she detects online.

Hier’s work has been likened to the vivid world of Lewis Carroll, indeed to experience one of her exhibitions is to become, for a moment, Alice entering Wonderland. And yet despite this torrent of cultural references, her work is both precise and elegant. It is the blend of kaleidoscopic colour, texture and form, as well as its sophisticated visual arrangement that so characterises her current exhibition, ‘Gridded and Girdled,’ on display at Y2K group in New York.

Stephanie Hier: ‘Gridded and Girdled’, 2019, installation view at Y2K group, New York // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

Sarah Messerschmidt: I’m curious about the titles of your works. They’re all quite punchy, almost like old-fashioned idioms, yet they’re also suggestive of something a bit darker. I’d Go A Mile For A Chuckle, Good Byes and Bad Hellos, and Don’t Leave Me In A Minor Key, for example, seem to have somewhat sinister resonances. How do you come up with these phrases and how do they relate to your work?

Stephanie Hier: In general, my work is made up of numerous disparate references, so I like to treat my titles in this way too. My work can be interpreted in a multitude of ways, and because a title offers defined context to a painting I like to throw a wrench into the narrative that emerges in any given piece. I’m also interested in how tone is created in a painting through the use of colour, imagery connotation, and title. In my current show the palette and imagery is optimistic and lighthearted on the surface, however many of the conversations I’ve had around the works turn to weightier and sometimes thorny topics. The conversation surrounding I’d Go A Mile For A Chuckle often turns to the economy and arts place within it and subsequently the place of craft culture within that. So I’m interested in this push and pull between context and form; the titles play into that as well. From a practical standpoint, the titles are often snippets of conversations I overhear on the train, phrases from films and books, song lyrics, quotes—really anywhere I encounter language. I keep long lists of potential titles and when I finish a piece I assign it a title from my list. I usually just intuit what feels right.

Stephanie Hier: Don’t Leave Me In A Minor Key, 2019, oil and latex paint on quilted hand-dyed linen, 60″ x 48″ // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

SM: Your work explores this very contemporary experience of surfing the internet, where there is an excess of data and high and low culture cross-pollinate. There’s a suggestion that the internet is impassive to individual tastes, yet algorithms are designed precisely for this purpose: to present each user with an individualised experience of information. Can you explain more about your choice of wording for ‘Gridded and Girdled’—to me, the title implies constraint—and how you connect the various elements of the exhibition in a, perhaps, algorithmic way?

SH: I do think about internet algorithms in relation to my work. I like the idea that images depicted in a series of paintings in a show can evoke the same feeling of surfing the internet or being presented with an “individualised” series of images online. But at the same time I think the idea that anything on the internet is actually individualised is a smoke screen. We’re made to think that we each have unique characteristics that warrant a personalised internet experience, but really we’re being nudged in certain directions. So perhaps the feeling of boundless information evoked in the show, as on the internet, requires some kind of constraint, maybe some gridding and girdling. Though I also thought of the title as a reference to the craft elements of the show: the gridded linen and the ceramic frames which girdle the paintings.

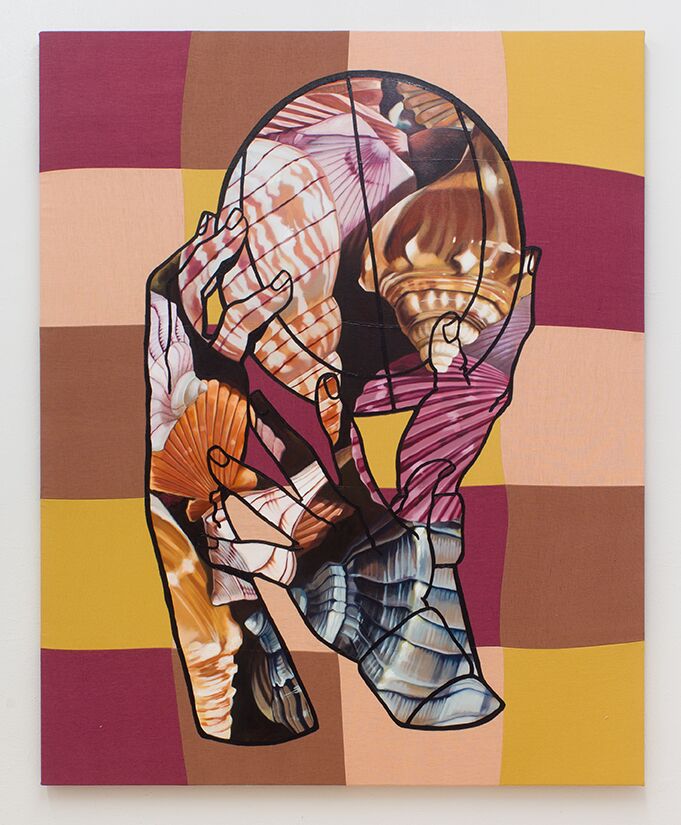

SM: You make a lot of references to modes of production, particularly via the motif of the hand, which turns up again and again in your painting. There’s an interesting conflict between the figurative under-paintings of your work, which traditionally aim to eliminate any evidence of the artist’s hand, and the very transparent way you reference the tactile nature of art, or the artistic process. Was this your intention?

SH: I like the way you put that. Broadly, I’m interested in the labour of artists—the ways in which it’s hidden and when it becomes blatant. By making semi-photorealistic paintings which, as you say, hide brush strokes (and reference some forms of traditional painting, specifically historical Dutch painting) and then obscuring that image with a graphic line drawing, often a hand, I’m creating a connection between form and content. In other words, I use the hand drawings as a lens or frame with which to view a painted image. There’s a relationship between the hand drawings and the images they crop; this is something I’m interested in exploring in each piece. I also see the hand drawings as a true ode to the hand, for lack of better words. We owe so much in this world to our hands and I feel that as artists we should honour that.

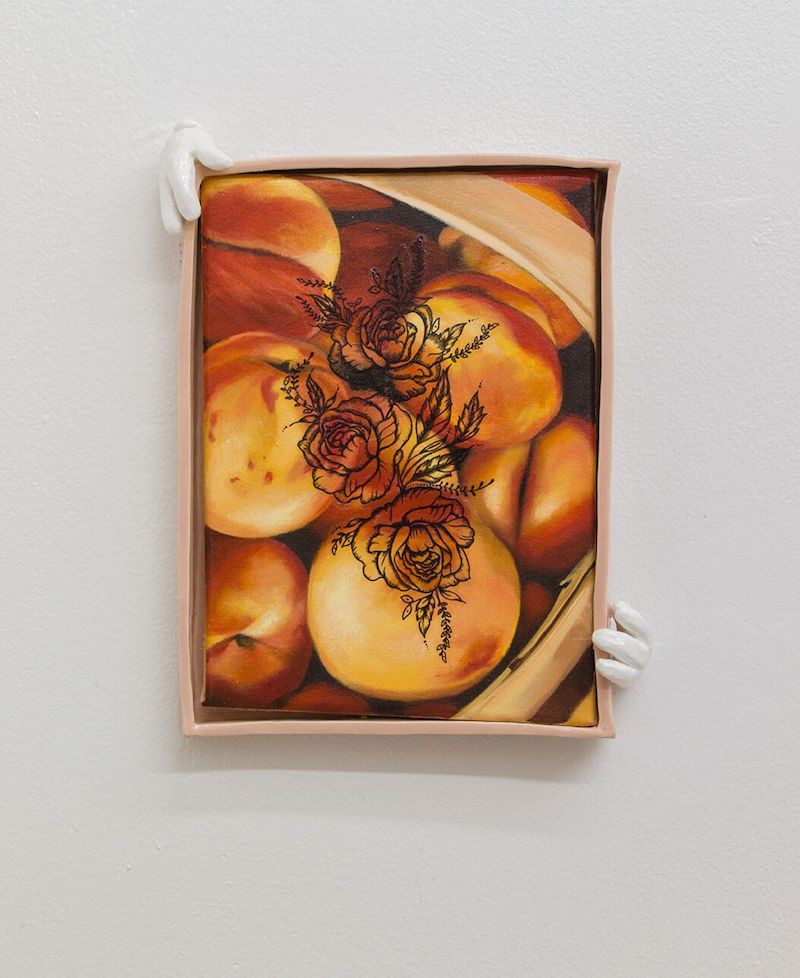

Stephanie Hier: The Empty Fridge, 2019, oil and temporary tattoo on canvas with glazed stoneware frame, 13x11x2″ // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

SM: I notice that food also plays a big role in your painting, and maybe in the context of the internet this relates to the consumption of images. In your work, food is both visually sumptuous and conceptually rich. Can you elaborate on why you return to this theme?

SH: Spot on, consumption is a major theme in my work, so depicting food is an obvious choice. However I often depict flora and fauna more broadly, so I guess food falls into that category as well. I’m interested in how loaded with meaning the natural world has always been. Something as simple as an apple can symbolise so many different things based on context. Also, the “natural” elements I depict aren’t really natural at all. They have gone through so many stages of representation—through photography, internet mediation, digital manipulation—that they are really removed from their original aura. I think pairing these quasi-natural renderings with other references and materials makes for a compelling image and narrative.

My work can also be really self-reflective, so, for example, the piggy bank image in I’d Go A Mile For A Chuckle can be interpreted as relating to consumption, in this case referencing art’s relationship to commerce. That said, I’m interested in putting the topic of art consumerism on the table, but I’m not too concerned with offering an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms of contemporary art. I prefer to think of my place as an artist as a mediator of images and not the prescriber of their meanings.

Stephanie Hier: Good Byes and Bad Hellos, 2019, oil on quilted hand-dyed linen with glazed stoneware frame, 9x14x2″ // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

SM: For this exhibition you draw on a motif of quilting, which seems a suitable topic for many reasons, not least of which is that with the practice of quilting, one can continually add new elements to an existing thing—quite like the way each of your exhibitions expands on the last. But what I also find interesting is this reference to craftsmanship, which is often at odds with the world of fine art. Where do you situate yourself as a visual artist, who is also interested in popular culture, who is also interested in craft?

SH: You’re right, the quilting is new to this exhibition and my exhibitions really do build on themselves. For this show I was thinking about the history of craft culture in relation to the ceramic frames I make for some of my works. I wanted to expand on this and incorporate another aspect of the craft world. I’m interested in closing the gap between craft and fine art, as I really think there oughtn’t be one. I want to create a non-hierarchical playing field where pop cultural ephemera, oil painting, craftsmanship, and visual elements of all kinds can co-mingle and exist on one plane.

I also should mention that the forms the quilts take is pretty significant. I set out with the plan to create a pixel-style gridded quilt and use colour maps of the imagery depicted on them to determine the colour palettes. While I was working on this show I also began trying to solve the Rubik’s Cube and also, as I often do, spending my down time working on crossword puzzles. Some friends pointed out to me that I was completely surrounding myself with grids and squares. In a moment of synchronicity I solved the Rubik’s Cube the day before my show opened. I think I subconsciously found a way to synthesise the way I compartmentalise the world in both my work and personal life—I guess I’m just drawn to the grid!

Stephanie Hier: More Twists Than A Barrel of Pretzels (detail), 2019, oil and temporary tattoos on canvas with glazed stoneware frame, 15x12x2″ // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

Stephanie Hier: ‘Gridded and Girdled’, 2019, installation view at Y2K group, New York // Photo courtesy Stephanie Hier

SM: You become so playfully involved in each exhibition, painting everything from the floors to the walls, hand-dying linens, fabricating ceramic frames, making animations and sculptures—I’m thinking specifically of work you made for the exhibition at David Dale last year. Everything is linked and no stone is left unturned. Yet this also means that there is an astonishing amount of work that goes into each show. I read recently one of Francis Picabia’s phrases about his relationship to work, in which he says, “My painting is a contest between life and sleep.” Is this also true for you? How do you plan your exhibitions to include so many distinct elements?

SH: I love that you reference Picabia, as some of his work is a huge inspiration for me. Though I wouldn’t actually characterise my painting as a “contest between life and sleep” because I’ve really integrated my life as an artist with my life as a whole. I live only a short walk from my studio and though I spend my days in the studio, I really consider all my waking hours to be part of my art practice. Being alive and alert in the world is a form of research for me. I occupy my time not spent in the studio by cooking, reading books and watching films or interacting with pop culture, like anyone. But I see this as research which provides content and inspiration for my work. Because of this, I’m also interested in playing around with multiple mediums. I work in video/animation, painting, quilting and sculpture because that mirrors the many forms of media in the world. I’m interested in the way these concepts we’ve discussed can change, or stay the same, when the form or medium changes. So yeah, a huge amount of my time goes into actual art-making and preparation for exhibitions, but because I’ve managed to integrate all aspects of my life into the work, it never feels like a contest.

Exhibition Info

Y2K GROUP

Stephanie Hier: ‘Gridded and Girdled’

Exhibition: Feb. 16–Apr. 07, 2019

373 Broadway, #E18, New York, NY 10013, click here for map