Interview by Alison Hugill // July 02, 2019

In her broad practice as a visual artist, writer and teacher, Dorine van Meel addresses and advocates feminist methodologies and self-organized forms of collaboration. Her video and performance works use poetic language as a political tool to dismantle patriarchal, capitalist and colonial structures. Often portraying architectural elements as visuals, she intersperses written texts with soundscapes that retain all the urgency of a call to action.

This year, van Meel’s video work ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’ was presented in the group exhibition ‘Persisting Realities’ at CTM Festival and in a larger solo exhibition at Hotel Maria Kapel (HMK), in the Netherlands. The piece interrogates notions of the bourgeois, nuclear family and the institutionalization of childhood through an interspecies and inter-textual narrative of hope, a suggestion that amidst all of these deeply entrenched power structures, a process of collective and generational disobedience—or, unlearning—is at work.

Dorine van Meel in front of the work ‘Disobedient Children,’ 2016 // Photo by Tim Bowditch

Alison Hugill: In ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’, the story of the Phoenix born from the ashes of its mother acts as a call to “think and live against the patriarchal, capitalist and colonial power structures that define the world as we know it.” What possibilities do you see for the next generation to unlearn these formal and legal codes that have been so deeply inscribed over centuries? In your view, what kind of alternative pedagogy is needed?

Dorine van Meel: ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’ is very much informed by me becoming a parent and asking myself the question of what it means to bring a child into this violent world. It urged me to go back to the work of some of my favourite feminist thinkers who were committed to break with the reproduction of the power structures you already referred to. Audre Lorde, Emma Goldman and Adrienne Rich have been particularly important to me, as thinkers who are not only committed to an interruption of the status quo but also hold fast to the possibility of another way of being in this world.

In ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’ I ask, for instance, what it could mean to be strong without being dominant, what a different kind of strength could be, one which embraces vulnerability but also persists in not being silenced. When it comes to the unlearning required for the recovery of such other ways of being, I’m especially interested in the notion of disobedience, both in our personal lives and in the institutions we inhabit. This includes epistemic disobedience: a refusal of mainstream narratives and a focus on the voices that speak towards justice – to let them take centre stage, make them into our role models. Instead of being overwhelmed with hopelessness in the face of it all, I want to be invested in a pedagogy that recovers possibilities and spurs to action. This means first and foremost to understand yourself as an agent. But such an agency is never individual, it always requires a collective endeavour.

Dorine van Meel: ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’, 2019, installation view at Hotel Maria Kapel, Hoorn // Photo by Bart Treuren, courtesy of the artist

AH: In your exhibition at HMK, as well as many other exhibitions you’ve created in the past, there is a discursive element that encourages visitors to engage on a theoretical level as well (with readings, printed matter or live discussions). What role does that play in your practice and why is it important to you?

DvM: I understand my artistic practice as a productive space in which some of the questions that confront us at the moment can be actively addressed and worked through not only by me, but through an interplay of different voices, be it those of peers or audience members. This interplay for me already begins with the role that reading has in my practice. I draw a lot of inspiration from the work of feminist writers, queer theorists and decolonial thinkers and it seems only natural to enter into a dialogue with them in my work and beyond, for instance in the form of reading groups, writing workshops or live discussions. These dialogues then, in turn, affect my thinking and shape my further practice of writing and video making.

Dorine van Meel: ‘Phoenix’s Last Song’, 2019 at Nottingham Contemporary, performance with Jules Sturm // Photo by Sam Kirby, courtesy of the artist

AH: In your practice and exhibitions you often collaborate with other artists (musicians, writers, students). Do you see collaboration/collectivity as a means to subvert the hegemony of single authorship and the hierarchical/capitalist notions it entails?

DvM: Collaboration has indeed become a really important aspect of my practice, in particular in the context of self-organisation. Sometimes these collaborations will take on a more discursive form, like the Southern Summer School, a self-organised educational programme on art, decolonisation and social justice. On other occasions, I literally try to open up my video work to different perspectives by inviting others to contribute via performative readings, as in the case of ‘Gentle Dust’, a series of collaborative events that speculated on the possibility of an exodus from the museum.

What interests me in works like this or ‘Farewell to Progress’ is that they allow a subject to be addressed by a multiplicity of voices rather than a single omniscient author. The collaborators will come to the project from different perspectives and lived experiences, but what we share is a political alignment. What I value in these projects is how they contribute to establishing a network of peers—not only artists, but also writers, composers and activists—that may work in different fields and socio-political contexts but have converging commitments. The idea that collective problems could be resolved individually is a dead end, so forming these kinds of networks and support structures is crucial for the kind of agency I mentioned earlier on. What is, for me, empowering about collaboration, especially when it is part of a practice of self-organisation, is that it shows we are not just dependent on existing institutions but can to some degree take charge of the conditions under which we act.

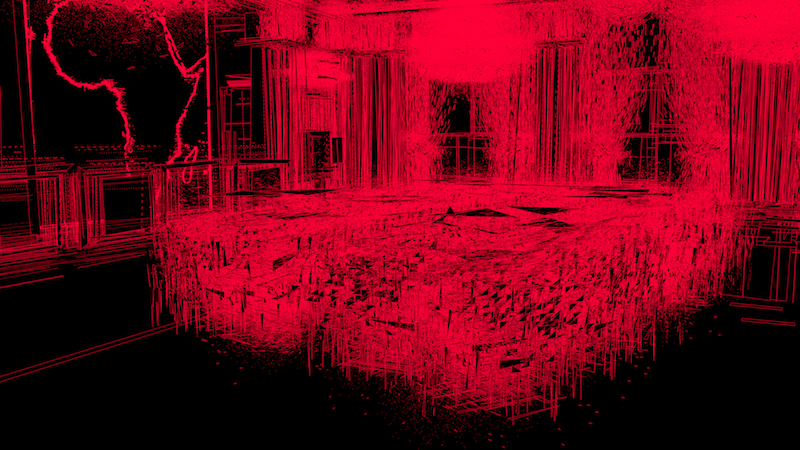

AH: In your exhibition ‘Beyond the Nation State I Want to Dream’, presented last year at Decad in Berlin, your video work of the same name envisions a dystopian (or perhaps frighteningly realistic) landscape—with red computer-generated visuals and industrial sounds—of a life ruled by (re)productivity and nationalistic binaries of Us vs. Them. Can you talk about the inspiration for that project?

DvM: In this project I wanted to look at the colonial history of the Netherlands—the country I’m from—and the ways in which this violence is still reproduced on a daily basis. Growing up in the Netherlands during the nineties meant being exposed to a specific type of celebratory image of the nation state: one that could be open and tolerant, “multicultural” and progressive. Our colonial legacy and the crucial role our forefathers played in the slave trade is carefully ignored, as is, more importantly, the way in which this legacy lives on in the present. The celebratory image of the Netherlands has been challenged by anti-racist protestors, whose contestation of both past and present forms of racism and white supremacy has been particularly effective in recent years and entered mainstream discussion.

In line with their call for justice, the work aims to picture an image of the modern European nation state that is not oblivious to its violence. Crucial to the development of this work were the extensive conversations I have had with colleagues from South Africa, including the artist and curator Simangaliso Sibiya. Conversations with him showed me that, in order for us to move forward, those in the former centres of colonial power need to address this past of colonial violence and ask what it means to take responsibility to stop its continuation in the present in all its various forms. One of the ways in which we try to do this is through the cultural exchange program Decolonial Futures that we organize at the art schools where we work: the Rietveld Academie and the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam and Funda Community College in Soweto. In ‘Beyond the Nation State I Want to Dream,’ I wanted to also contribute to this process as an image-maker and challenge the canon from a visual perspective.

Dorine van Meel: ‘Beyond the Nation State I Want to Dream’, 2018, film still of Berlin Conference // Courtesy of the artist

AH: There’s one line in the video: “I’m not a teacher and you are not my students. Or maybe all of us are students and all of us are teachers. And what will that allow? The contracts we sign to keep us in place….” In your own work as a teacher do you also strive to breakdown these boundaries and hierarchies forged by monetary concerns? What effects does that have?

DvM: I feel very fortunate to have the opportunity to work with young artists in a teaching environment because I think this is a space where critical thinking can be foregrounded, curricula can be challenged and a space can be opened up in which students can bring in their different knowledges and lived experiences. When I start working with a new group, the first text we read is always Audre Lorde’s essay ‘The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,’ which I use as a starting point to discuss what it might mean to position and voice oneself, also as an artist. I try to encourage students to find this voice through quick writing assignments, which I am interested in as a device to give space to students who do not speak easily in larger groups. Breaking down the hierarchies in the classroom is indeed important to me, at least to the extent to which such hierarchies can be harmful. Instead of claiming a neutral and non-negotiable authority as a teacher, I try to be open about my own practice, process and the subjective position from which I speak in class. Another aspect important to my teaching practice is the insistence on the collective responsibility we have as a group: creating a meaningful space that includes each of the students and facilitates critical thinking and growth is hard, necessarily collective work.

Dorine van Meel: ‘Gentle Dust’, 2018, HD Video, still // Courtesy of the artist

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Unlearning.’ To read more from this topic, click here.