Interview by Lucia Longhi // Oct. 04, 2019

Davide Quayola belongs to a generation that forged artistic production in the digital world, his works intersecting between a classical iconographic legacy and a contemporary digital language. An increasing number of artists are using new technologies and artificial intelligence as mediums, aware of their contemporary relevance. However, for Quayola, technology is not only a tool, but also and above all the subject matter of his investigation. His work aims to research and present transformations that new technologies are activating within human evolution. Computers are improving and changing at an ever-increasing speed: they were programmed to look and behave like humans, but today they are so advanced that many tasks and analyses they deliver are not yet easily accessible to humans. Thus, we are now transforming our faculties, our way of thinking, our collective representations and our visual systems, to approach this new standard. For Quayola, technology manifests as an intelligent colleague to collaborate with, and not simply a machine to use and control.

Davide Quayola, portrait // Courtesy of the artist

Lucia Longhi: Employing the most advanced technologies and robots, your research places itself within one of the most relevant contemporary artistic discourses, the dialogue between man and machine. How do you use robots and artificial intelligence?

Davide Quayola: What fascinates me are the codes of technology not as a vehicle to reproduce, or represent, a subject, but rather as the subject of investigation. Today, a lot of art is produced with the help of technology. It is an interesting and, in my opinion, natural path, as most production is outsourced to software robots in any realm. However, I’m not interested in just using computers, but rather working together with them. I want to investigate how an artificial intelligence proceeds when it has to produce an image – given an input. I think it is interesting to study how robots and AI see and represent things. I am fascinated by how some patterns created by nature are reproducible by mathematical functions (for example, when we see a stormy sea in a film, it is a simulation made with mathematical functions). The functions used to describe fire, wind, sea, clouds, forests are very similar, but calibrated a little differently. I am intrigued by the function not as a tool but as a subject. So, in the end, what you see is not the painting of a landscape, but the painting of a function that describes a landscape. It is a complexity of layers that can only be generated by mathematical functions. And, for me, it’s challenging to explore these functions within the context of our classic visual heritage, which includes the natural world, still life and landscapes.

Davide Quayola: ‘Pluto and Proserpina,’ 2019 // Courtesy of the artist

LL: In fact, the images you present refer to well-known iconographies—classical sculptures, Renaissance paintings or landscapes, i.e. from the Impressionist heritage—that you rework and return transformed. However they are not, in all respects, the real subjects, but rather a pretext to activate a new process of representation. Can you explain what exactly is the transformation these classic images undergo and what is the role they have in this type of process?

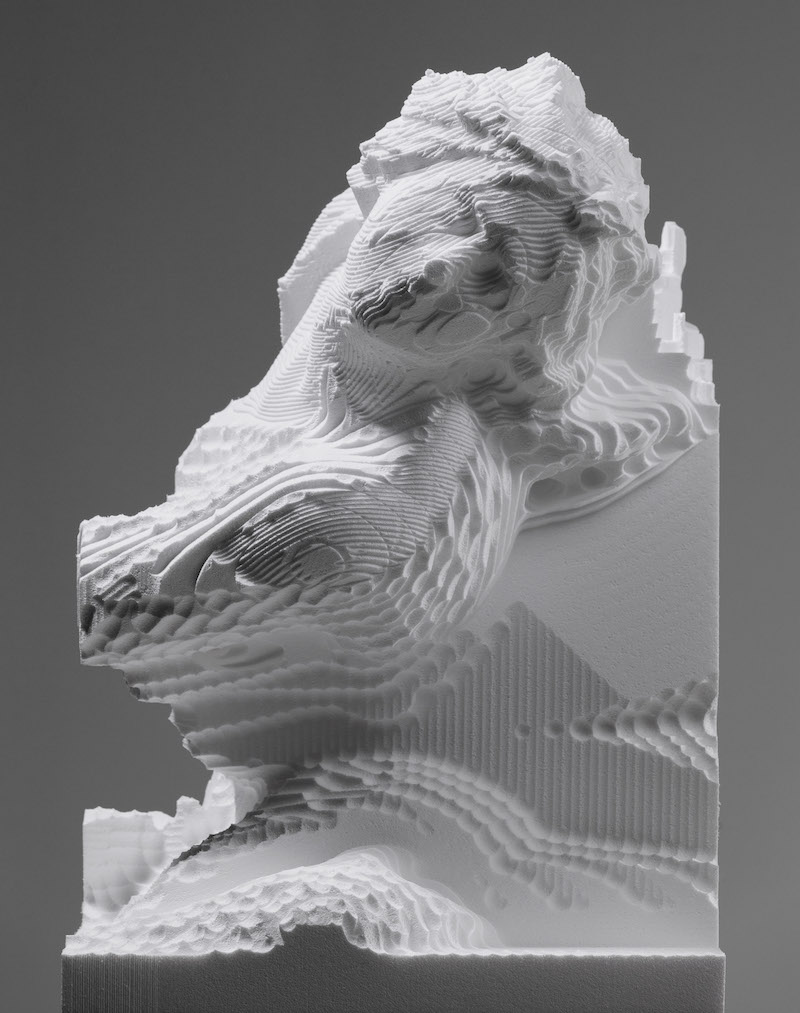

DQ: For me, classic icons and references have the same role they had for the artists of the past: a garden, the Laocoon, the theme of Judith and Holofernes… Artists were not interested by these topics as subjects, but rather as a place to explore a methodology of representation. I am fascinated by the idea of iconography as a pretext, as a vehicle to carry out new research, a new process. Consider my sculptures: a basic model actually exists, but it is handled as a target. A target that, however, will never be reached, as I let the robot carve the space around that object with many different simulations. What I do is explore the infinite possibilities potentially embedded around that model. The more I go on, the more I realize that a precise historical subject is no longer necessary, as the technique already has a relationship with the heritage (think about Michelangelo’s non-finito). I mean, the final object clearly recalls a classic image. But the reference is no longer literal.

LL: So basically the transformation you stage doesn’t consist in taking paintings or classic artworks and transforming them. What you do is considering their matrix (for example, the nature in which Van Gogh used to plunge, or a Bernini statue) and from there you activate a process of representation—and therefore, a visual abstraction—that works differently.

DQ: Exactly, and that way of seeing, that new visual system, is the computer’s way of seeing. As I said, what is important to me is working in collaboration with an intelligence that is different from ours. In this respect, my work is a meta process: the representation of a system of representation. The result is therefore not only a new observation on a topic, but also and, most importantly, on society. I am fascinated by how machines are changing the way we see the world. Computers are constantly changing, looking more and more like us, but ultimately we too are transforming ourselves, evolving towards technology. As an artist, it’s exciting to have the chance to witness this evolution.

Davide Quayola: ‘Jardins d’été,’ Video, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist

LL: I think that the contemporary man perhaps can identify more with your images, than with a Van Gogh painting, because they are built with the codes of the present age. The way we picture reality, our categories of thinking, our visual system, our aesthetics and our sensibility are now set according to the codes of the digital world. In short, man and machine meet halfway. And your job is placed right there…

DQ: Yes, I work exactly on that point of intersection, where man and technology meet. As a human, I’m not interested in controlling the machine. The process of transformation is precisely this, the transformation we humans are experiencing collectively.

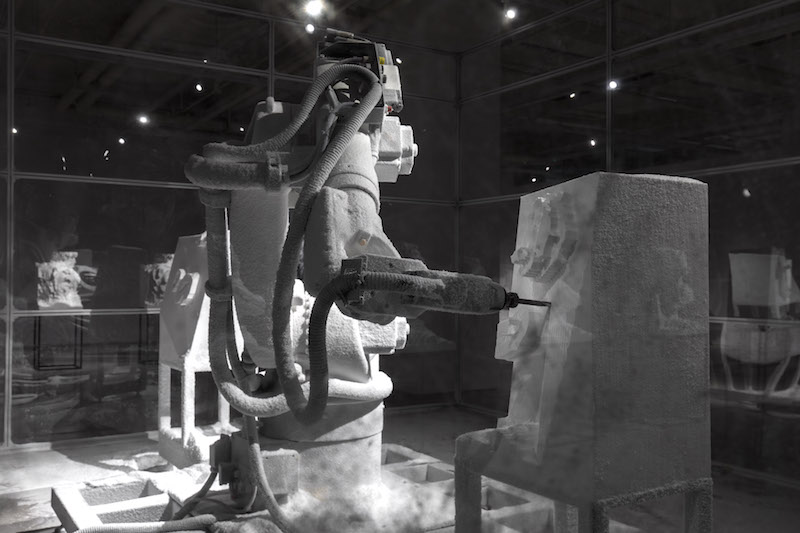

LL: Your work focuses on the process rather than the finished work. In this respect, once again we can say it blends in with the History of Art, bringing performance art to a further stage. Can you expand on this: the live performativity in your works?

DQ: Yes, I’m interested in the process. I’m going more and more in the direction of transformation process in real time. With the robots, I finally realized what I had in mind for a long time, namely, showing the robot caught in action in the workshop. My artistic path has been quite linear: I started with digital painting and videos. There was still no intimacy with the robot. From the paintings I started working on some volumes, in order to make videos. And there, some interesting forms emerged. So I thought I’d try to materialize them. As I was watching these robots sculpting, I started to engage with them and think about how to use them. ‘Sculpture Factory’ is an example of this type of performance. The public can watch the robot working in real time. What happens in the paintings is the same. I am developing softwares that modify images in real time, through algorithms that reproduce natural patterns and classical pictorial techniques, such as the Impressionist brushstroke. They look like paintings and yet they originate from a completely different logic. I am discovering an infinite potential.

Davide Quayola: ‘Sculpture Factory’ at HOW Art Museum, Shangai, 2019 // Courtesy of the artist

Davide Quayola: ‘Remains,’ 2017, print on Baryta paper // Courtesy of the artist

LL: So is your research moving in a new direction? How?

DQ: I am continuing the research on trees scanning with the most advanced laser technology (‘Remains’). That is also is a way of depicting nature with a traditional technique, in a way (en plein air), and yet with a completely different way of seeing, a different logic. They stay so true to the original landscape, being made of millions of dots, which are the result of many hours of scanning from different points of view outdoors. This is why I print them in a super large format: the digital composition of the image must be visible. We could say they are hybrid images, both natural and digital.

I’ve recently started to explore a material I’ve been thinking about for some time: marble. It is the material of classical sculpture and, therefore, it is a further link with our heritage and it contains a great potential. For me, the process must be visible in the work, and marble allows me to engage with it in a three ways: the geological transformation embedded in it, the extraction process by the human being and the intervention of the robot sculpting it.

Davide Quayola: ‘Laocoön’ #D20-Q1, 2016, Sculpture, pulverised white marble // Courtesy of the artist