Interview by Alison Hugill // Oct. 08, 2019

Elvia Wilk’s debut novel ‘Oval’ presents its readers with a parallel world; the city of Berlin is almost imperceptibly different from its current state, but many of its quintessential qualities are ramped up to near-Sci-Fi effect. The social subset of perambulatory artists and cultural consultants— the so-called “creative class” of expats that the city plays host to—runs wild in the novel, and the corporate greenwashing of sustainable architecture is exposed as a sinister menace underpinned by Berlin’s rampant real estate speculation. The main characters, Anja and Louis, are caught up in this messy matrix of experimental architecture and design, extending beyond their eco-housing settlement and into their relationships with one another, their friends and the city. In ‘Oval,’ Wilk transforms Berlin into one of its possible futures, or perhaps, rather, an alternate reality. We spoke to the author about how she envisions urban transformation and sustainability practices in ‘Oval’ and how space is central to power struggles worldwide.

Elvia Wilk, portrait // Copyright Nina Subin

Alison Hugill: ‘Oval’ is your debut novel. Given that you have lots of experience writing criticism and shorter, essay-style articles for cultural publications, what was the process like for creating such a layered and cross-disciplinary plot (encompassing science, architecture, urban planning, real estate speculation, art, love, grief and drugs, to name a few subjects)?

Elvia Wilk: The process was long! It took me several years of experimentation to find what felt like a coherent structure with all the elements of a novel: plot arc, fully fleshed-out characters, a world with its own ecological and economic systems. Along the way, I did a ridiculous amount of research, much of which I wrote about in the form of essays. Writing nonfiction relating to elements of the fictional world helped me work out my ideas and imagine ways that reality could be tweaked in the book. For instance, I did interviews and archival research for an essay about the history of artists working with and within corporations; much of that material and the questions it generated about complicity and critique ended up expressed in the novel. But the core of the writing process was always a personal, intimate one—testing my own decisions, beliefs and attitudes by placing the characters in tough situations and seeing how they would react.

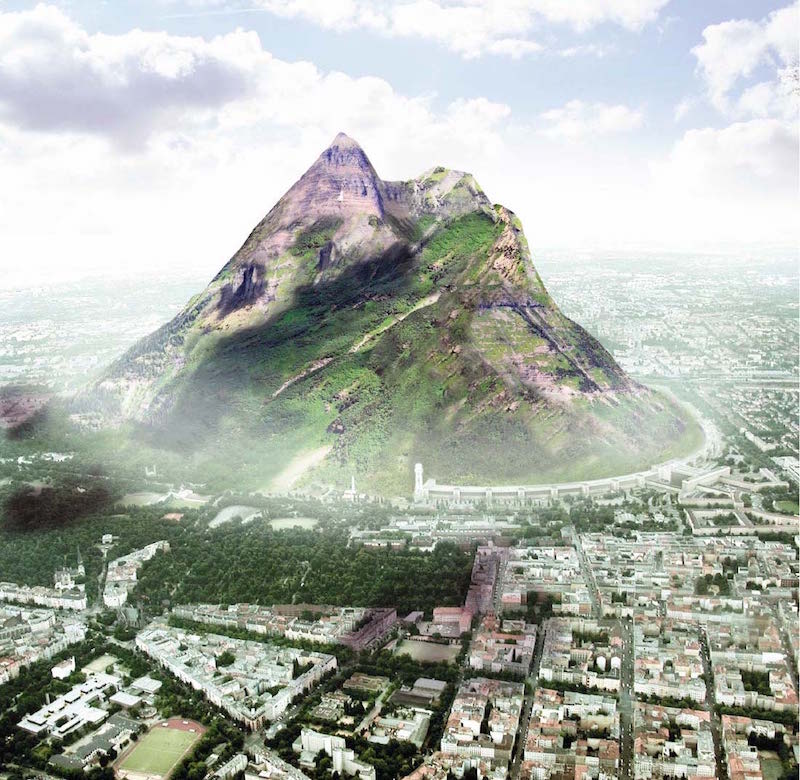

AH: Let’s talk about one of the main settings for your novel: the Berg. It’s a speculative design by Mila Architects from 2009, for an artificial mountain to be built on Tempelhofer Feld. Why did you choose this setting and how did it shape your narrative about Berlin or vice versa: how did you reconstruct and enhance the existing project for your story?

EW: The proposal by Mila, now a decade old, was quite a simple one: rather than develop Tempelhofer Feld with housing or museums or anything else, let’s dump a mound of earth on it large enough to form a mountain, what they called a “vertical nature park.” I love the dramatic and megalomaniac statement for visible un-development, which poses an alternative to the constant imperative to densify and maximize urban space. The architects’ proposal was ultimately not to build the mountain, it was to act as if the mountain had already been built; they launched an ad campaign to proliferate the Berg’s image, the idea being that a city icon doesn’t need to exactly exist in order to become emblematic.

As an image, it successfully busted open the urban imagination to alternatives—after all, Tempelhof is still undeveloped. With this proposal, the nature of Tempelhof as a space for projection and speculation became very clear to me, and I wanted to adopt the mountain for my own kinds of speculation. The two main characters in the book live in a semi-dystopian eco-settlement on the side of the mountain (not included in the Mila proposal). The mountain is both a manifestation of the isolation they feel in their relationship, and a staging ground for their ethical and political dilemmas regarding how to live a sustainable life.

Mila Architects: ‘The Berg’, 2009 // Copyright Mila Architects

AH: The failure of the sustainable eco-housing project on the Berg is blamed on the incompetence of its inhabitants. Anja and Louis are indeed cutting corners as far as their commitment to waste-free living goes. What do you think are the biggest challenges to implementing utopian designs for sustainability, like the one you have created in ‘Oval’?

EW: Companies and governments with less than excellent sustainability practices have been known to run ad campaigns asking consumers to change their behavior. Consumer habits can and should change, but I don’t think shovelling responsibility for environmental preservation onto the level of the individual is a comprehensive solution. Individual decisions do matter on a collective level, and there are specific pressure points within consumption cycles that offer important possibilities for leverage; we should do these things. But major change has to also be structural, meaning on the macro scale. The fact that some Amazon workers forgot to recycle their coffee cups this morning is not the problem—Amazon’s top-down system of overproduction, waste and exploitation is the problem.

AH: The architectural references to Berlin as well as a main character, Louis’, hometown in Columbus, Indiana abound. You talk about how the area around Potsdamer Platz has changed since the Fall of the Wall, but also how corporate interests have always played a role in ushering in new designs and urban transformation in Berlin and elsewhere. Your fictional Finster could very well be a stand-in for the current Berlin real estate menace Deutsche Wohnen. Can you talk about some of the parallels you see between Oval’s Berlin and the one we are currently inhabiting? How distant is this future scenario you’ve envisioned?

EW: The book is described as “near future” but I’m not so interested in its predictive capacity. Everything in the book is just a step sideways from what’s happening now, not a step forward. No fictional person or corporation is literally modelled after an existing one, but I tried to manifest general tendencies, aesthetics and systems in place through, for instance, the almost over-the-top sinister corporation Finster. Simply describing Finster’s workings, I think, makes you realize how bizarre and sinister so much of what’s happening right here and now already is.

You’re right that much of the book is occupied with tracing architectural transformations and tracking how the control of space is central to power struggle in most cities. As Fredric Jameson says, “today, all politics is about real estate.” Louis’ hometown of Columbus, Indiana, is a touchstone for me when trying to pin down the drivers of development and the role of architecture in shaping culture. Starting in the 1950s Columbus became a sort of proto-creative-city, thanks to the philanthropic scheming of a wealthy businessman who wanted to populate his hometown with fantastic mid-century modern architecture. I wanted to constantly interweave the story of the evolution of Berlin’s urban landscape with other architecture stories to track what they have in common and what they don’t. And, of course, I’m endlessly fascinated by the figure of the architect as a protagonist—when most of what gets built has nothing to do with an individual vision.

Mila Architects: ‘The Berg’, 2009 // Copyright Mila Architects

AH: The novel is peppered with ominous weather updates, delivered via text message from a character called Dam. As readers, we have a sense that the seasons are changing rapidly, sometimes within the span of a day. Why was this plot device important to your story?

EW: The constantly changing weather patterns are partially intended to reflect (and explain) the sense of paranoia, opacity and uncertainty that most of the characters live with. I think the suspicion that there is a conspiracy going on somewhere is a very real aspect of the contemporary psychological condition! That doesn’t mean I’m a conspiracy theorist, but the feeling that power is working behind a one-way mirror, where it can see you but you can’t see it, creates a sort of constant mood that I wanted to underpin the story. The weather updates that Dam sends out via text blasts are also a formal device, poetic snippets of text trying to describe the ineffable or indescribable that offer a break in the movement of the plot and signal shifts in the characters’ internal weather, so to speak.

AH: ‘Oval’ (both the novel and the eponymous pill) obviously targets a certain demographic of young, international Berliners who reside in a small radius around Neukölln, are precariously employed and involved in creative industries. Artists and consultants, mostly. Does the story have resonance for those less familiar with this societal subset? How has it been received outside of Berlin or even in different contexts within the city?

EW: The title of the book comes from a pill named Oval that one of the main characters, Louis, develops halfway through the book. The pill is meant to induce financial generosity in the user, and Louis introduces it to the public by way of dealers in nightclubs—an easy way to start an epidemic in Berlin! Yes, this particular economic and cultural class of people is Berlin-specific in some ways—such as their particular flavor of apathy and the nature of their precarity—but part of what makes them a class is in fact their mobility and access. They are able to travel as they choose and can support themselves by working internationally. In our unfortunate common parlance they are the “international culture class,” not the “locals”; and they are the “expats,” not the “immigrants.” In that sense, their attitudes and dilemmas as portrayed in the book probably feel familiar to privileged, mobile people living in many urban contexts.

There is plenty of resentment, both warranted and unwarranted, against this nebulous class in the cities where they live. Some of that resentment has indeed manifested as resentment toward the book. But I hope that anyone can read it and enjoy it and understand it as a self-reflective report from inside the zone, rather than a navel-gazing report that reinforces the boundaries of that zone.

Elvia Wilk: ‘Oval,’ June 2019, book cover // Copyright Soft Skull Press and Elvia Wilk