Interview by Juan José Santos Mateo // Nov. 22, 2019

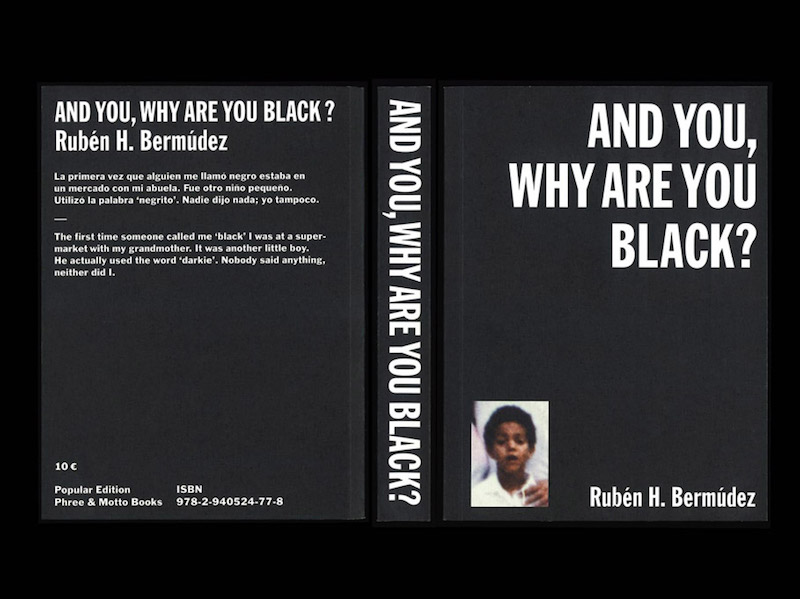

The creator Rubén H. Bermúdez caught the attention of a system that was strange to him—contemporary art—thanks to his 2018 photo book ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’, in which he reflects, through his own images and those of outsiders, on the way in which blackness is represented in Europe. During our interview, he confessed that with this project he began his own process of decolonization, unpacking the racism underlying the question that everyone who met him asked: “if you were born in Spain, why are you black?”

Currently, his project is exhibited at the CA2M art center in the neighbourhood of Móstoles, where he’s from, next to a video that shows the performance ‘They shouted “black” at me’ by Victoria Santa Cruz. In our conversation, we discussed many issues related to blackness: from the persistence of the cliché of the “White Negro,” established by Norman Mailer, to latent racism in films like ‘Back to the Future II,’ reinterpreting scenes like the one in which Marty returns to a nightmare at Hill Valley and finds a black family living in his house. Sometimes, as is the case in Bermúdez’s artistic project, we don’t need subtitles; the images speak for themselves.

Rubén H. Bermúdez, portrait // Photo by Matias Costa

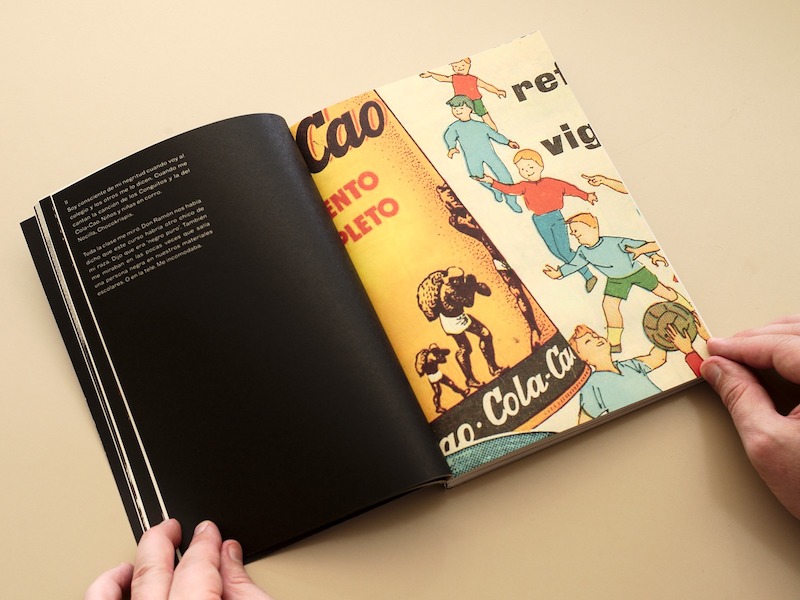

Juan José Santos Mateo: ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’ is a photo book from the perspective of blackness in the first person: a mixture of a family album, an appropriated historical archive of colonialism and slavery as well as an assemblage of pop culture images from films, music and advertising. Was this project conceived as a palimpsest of how occidental black people are represented, or was this format developed during the process?

Rubén H. Bermúdez: The creation process was quite chaotic and, perhaps, superficial. At first, I only knew that I wanted to make a photo book and that the title would be ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’ It was an excuse to explore my blackness. I began to accumulate images that were related to blackness in Spain, with its history and its representation, but also from my family album or from pop iconography. I started a blog, which would later become an Instagram account, where I began uploading all of this. I also began to remember and to write down different milestones or anecdotes from my life that were related to race. I didn’t have a very clear idea of what I was doing.

Over time I got a grant, and somehow I lost control of the project. One of the sponsor’s conditions was that in a year I should publish the book. I remember it as an erratic and very stressful process. I had accumulated images of all kinds of different formats, there were public and private ones, taken by me or taken by other people, and they were all in the same folder. That was all I had. The deadline approached and I had to make decisions, up till then I never knew what I was going to do. It helped me a lot to think about the reasons for which, and for whom, I was making the book.

It is important to say that there are not only images of my family album, of the slavery / colonialism archive and of pop iconography, but there are also images, for example, of Menelik II or of the Songhay Empire. Sometimes it seems that the history of Africa began with the arrival of Europeans and it should be noted that, no matter how obvious, this was not the case.

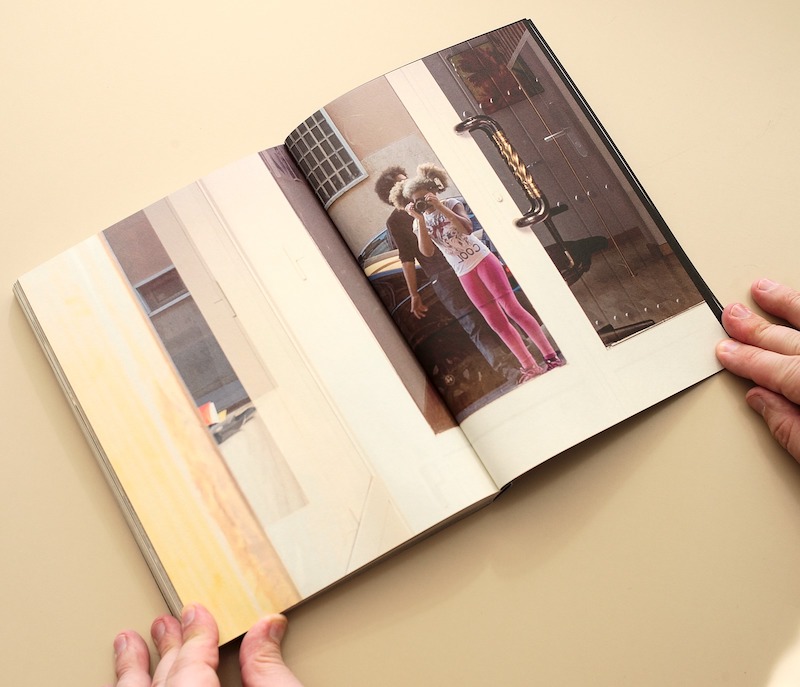

Rubén H. Bermúdez: ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’, 2018, photo book // Courtesy of the artist

JJSM: A particular aspect that is striking compared to other cultural projects focused on decolonialism is that no painful images or images of black people suffering appear here. I imagine it was deliberate, right?

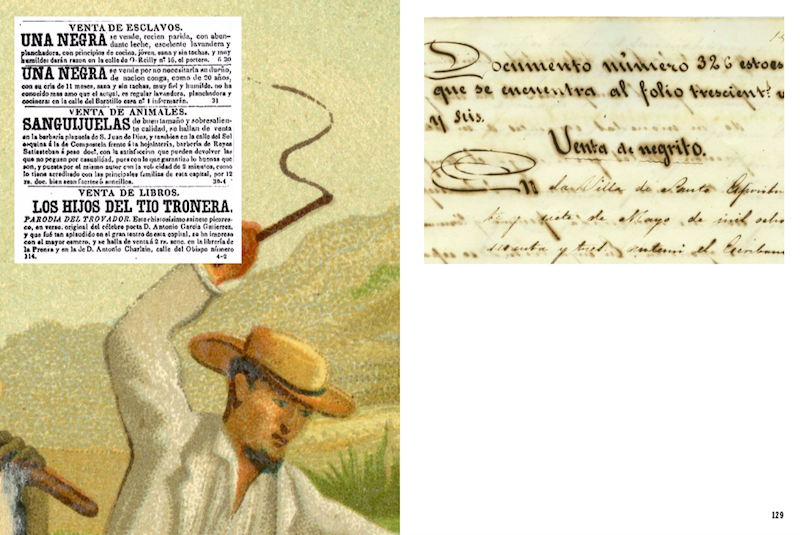

RHB: Yes, it was deliberate. I accumulated a lot of violent images while researching slavery in Spain, Spanish colonialism or what has been happening on the current fence of the Spanish-European border with Morocco-Africa. There were many terrible, painful images of violence and death.

Connecting with the previous question, I decided that my book was going to be spoken from my perspective, as I was greatly influenced by the book ‘Between the World and Me’ by Ta Nahisi Coates, and that I was going to address another black person in Spain. From that place it was impossible for me to show, again, images of black people suffering. Neither did I want to see them, nor did I feel that my audience would like to. I think it was a wise move.

Rubén H. Bermúdez: ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’, photo book // Courtesy of the artist

JJSM: You have stressed that the development of photography coincides with the European colonial expansion. So, in your opinion, you cannot separate one from the other. Then decolonization becomes something of the technique itself, of photography. How does that idea connect with ‘And You, Why Are You Black’?

RHB: During the year of the grant, they gave me a copy of ‘Photography, Anthropology and Colonialism (1845-2000)’ by Juanjo Naranjo, and it hit me hard. I understood that I was exploring my blackness through a tool—photography—that has traditionally been a very important agent in the construction and dissemination of racism. I did’t discover anything new. As I went deeper into these ideas, I realized that I was not comfortable with the practices of traditional photography. I didn’t know what to do with the portraits I had taken in Malabo [Guinea]. Little by little I accepted that my way of photographing, at least in this project, would be re-signifying existing images. ‘My White Friends’ by Myra Greene, is a work I have to quote. I was shocked and affected a lot by it. ‘The Watermelon Woman,’ a 1996 film by Cheryl Dunye, too.

JJSM: Although this project involved a process of decolonization in your case and, surely, in the case of many of its users, for you, racism in Europe is a structural issue, not an individual one. What examples did you find in your work process that you think best represent that structural racism?

RHB: In Spain, racism is mostly seen as a moral and individual matter: “I am a racist, I am not a racist.” There is no reading of racism as a power structure, nor is there a debate about institutional racism. The southern border, the Detention Centers for Foreigners and racist identity controls are now part of this structure. “Spanish people first” followed by “Immigrants are very useful for the economy.” It is a horrible framework, as Europe is a fortress. But I don’t think I’m the one who should explain racism.

Yet, I can advise you to listen to different voices from the afro scene in Spain. The literature of Lucía Asué Mbomío, or the theater of Silvia Albert Sopale, are two great examples. In photography, I am close to Agnes Essonti, we have each other as references.

Rubén H. Bermúdez: ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’, photo book // Courtesy of the artist

JJSM: The format of the book is very similar to ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ by Frantz Fanon. Perhaps one of the motivations of this appropriation on your part is that it seems that by many advances that have apparently taken place since the publication of Fanon’s book in 1952, things have not changed so much?

RHB: It’s really kind of a tribute. The artist Daniela Ortiz gave me an edition of ‘Piel Negras, Mascaras Blancas’ published in Havana in 1969; beautiful. We decided to use it as a reference. It was small, a popular edition, probably sold very cheap and passed from hand to hand, and is simple in appearance. I intended my book to look a little like it. The designers of Koln Studio helped me a lot, and the truth is that I love seeing Fanon’s book alongside mine. The book has tricks and games, which I think nobody understands, but sometimes there is someone who writes to tell me something he has discovered, or sees, and it is great.

Rubén H. Bermúdez: ‘And You, Why Are You Black?’, photo book // Courtesy of the artist

Exhibition Info

CENTRO DE ARTE DOS DE MAYO (CA2M)

Rubén H. Bermúdez: ‘Collection Capsule: Y TÚ, ¿POR QUÉ ERES NEGRO?’

Exhibition: Oct. 10, 2019 – ongoing

Av. Constitución 23, 28931 Móstoles, Madrid, click here for map