Interview by Jack Radley // Dec. 17, 2019

Moroccan-born, Berlin-based artist Bouchra Khalili never centers herself in her narrative work. Instead, she collaborates with individuals to radically rethink our understanding of the complex positions inhabited by those forced to move illegally. Khalili originally trained as a film historian in Paris; her work employs a masterful understanding of ethical methodologies to frame citizenship, labor and the politics of language. One of her most iconic works – the knockout eight-channel video installation ‘The Mapping Project’ (2008–11), exhibited at MoMA in 2016 – presents an alternative position to mapmaking that testifies to individual journeys of illegal border crossings as lived manifestations of political resistance. On the occasion of her commission for the facade of Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (nbk) in Berlin, ‘In Girum,’ Khalili and I discussed her work’s politics and poetics, its formation and its potential to advance decolonial thinking.

Bouchra Khalili: ‘In Girum,’ exhibition view Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, 2019 // © n.b.k., photo by Jens Ziehe

Jack Radley: Ghosts linger throughout your work. Your film ‘Garden conversation’ (2014) reflects on the historical resonance of a January 1959 meeting between revolutionaries Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Abdelkrim Al Khattabi, which has been widely reported as a historical fact but never documented. How do ghosts help us rethink our collective present?

Bouchra Khalili: To answer your question, I have to first emphasize that I come from Morocco, a place that has syncretic and maraboutic traditions. We do believe in spirits and ghosts, and we do know that they remain with us.

But it would be too easy to limit my answer to biographical details. I guess that my interest in “ghosts” is maybe even more related to history, and more specifically to the broken promises of collective emancipation that are still haunting us. ‘Garden Conversation’ – similarly to ‘Foreign Office’ (2015) – was in my mind many years before I could produce it. In fact, I had both projects in my mind even before I became an artist: I grew up being told the stories that both projects narrate. Those stories are part of the legacy of the history of liberation and decolonization in North Africa.

It is often forgotten, but the region has been going through major crises for almost 200 years. Those countries had to first free themselves from colonial powers, which took decades (Algeria was a French colony from 1830 to 1962, Morocco from 1912 to 1956). Then, the region had to struggle against oppressive regimes and the various faces of neo-colonialism: this has been going on for more than 60 years now. So, when the uprising started in Tunisia, then Egypt, I was surprised and full of hope and, at the same time, I could not ignore that what was quickly labeled as the “Arab spring” actually fit into the long-term history of struggle for liberty in the region. And this history is not over: it manifests itself in new forms, as currently in Iraq, Algeria and elsewhere.

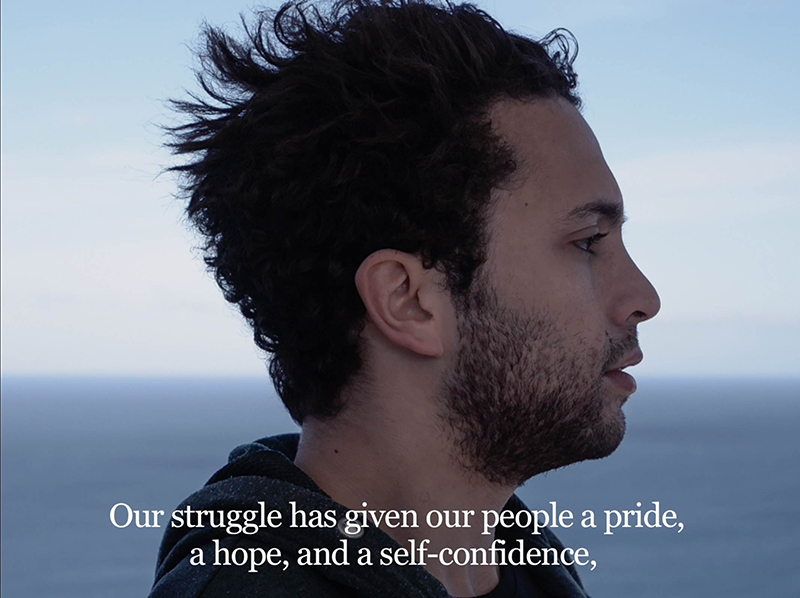

Bouchra Khalili: ‘Garden Conversation,’ 2014, 18′, Color, Sound // Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier

JR: In regards to your work that explores the memory of anti-colonial struggles, how do you strike a balance between poetics and politics?

BK: It’s a hard question to answer. There’s no such formula for producing these works. Rather, let me share a passage from Jean Genet’s introduction to ‘The Prison Letters of George Jackson’ (1970), which I’ve been meditating on for many years:

“If we accept this idea, that the revolutionary enterprise of a man or of a people originates in their poetic genius, or, more precisely, that this enterprise is the inevitable conclusion of poetic genius, we must reject nothing of what makes poetic exaltation possible … because poetry contains both the possibility of a revolutionary morality and what appears to contradict it.”

What I’ve been trying to examine for more than fifteen years now is: what is this form of poetry that arises from collective liberation and singular forms of resistance?

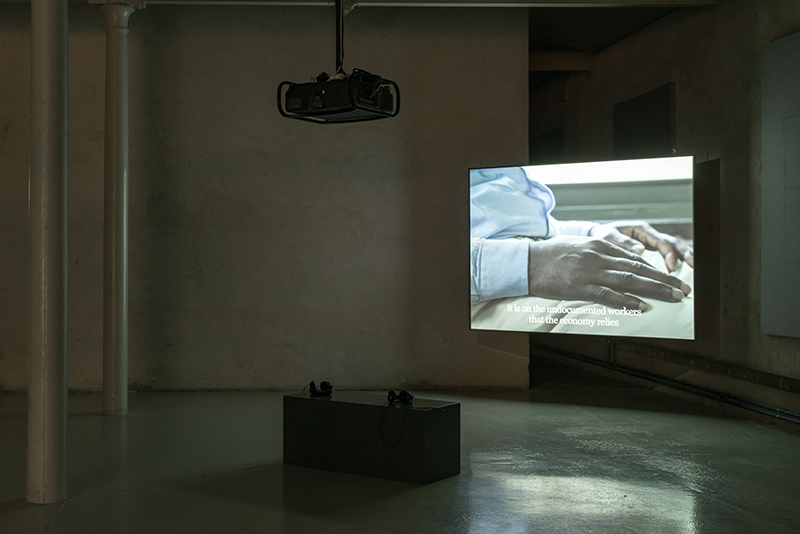

Bouchra Khalili: ‘The Mapping Journey Project,’ 2008-2011, Video installation, 8 single channels, Installation view of the exhibition, “Bouchra Khalili: The Mapping Journey Project. The Museum of Modern Art, New York // Photo by Jonathan Muzikar, Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier.

JR: You use individual stories to articulate and amplify collective voices in works like ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ (2008–11) and ‘The Speeches Series’ (2012–13). However, you are clear that none of these are “interviews.”

BK: None of my work in film and video is based on interviews because it is the opposite of the practice I have developed in the last 15 years. To quote the words of French sociologist Patrick Champagne, referring to the representation of minorities in media: “If this representation leaves little space for the discourse of the dominated, it is because their voices are particularly difficult to hear. They are spoken of more than they speak.” It’s what we still often see in most media reports, and many documentaries and artworks presenting themselves as works on “migration” with the best intentions but nevertheless relying on voice-over or appropriation by others of the voices of the ones concerned in the first place.

What was at stake in a piece like ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ was preserving the “opacity” of the subjects as defined by Edouard Glissant: “Why must we evaluate people on the scale of the transparency … As far as I’m concerned, a person has the right to be opaque. I can accept what I don’t understand.” Following Glissant, I believe that respecting the “opacity” of otherness opens up to a decolonized conception of universality. And even when faces are shown in my other works, such as in ‘The Speeches Series,’ there’s still a sense of opacity that is preserved, relying on a “distancing effect.”

In fact, my approach – or if one wants to call it a “method” – is essentially based on long conversations, during which I do not ask questions but rather listen. I let the participants in my projects speak. Giving them the time to speak freely also allows them to take possession of their own voice, their own story and their own narrative. As I termed it in an interview with Omar Berrada: this process is a form of “writing without writing.”

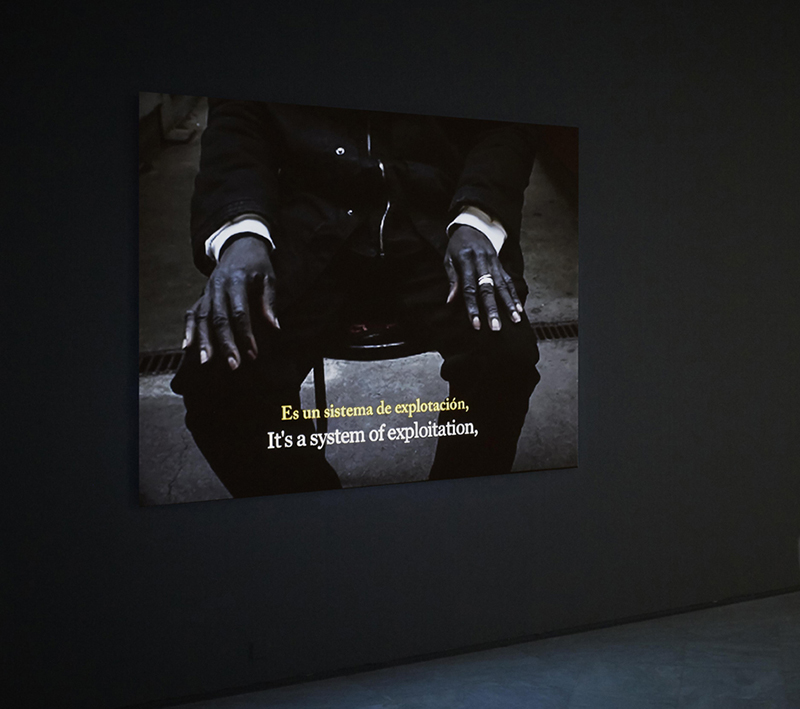

Bouchra Khalili: ‘Mother Tongue,’ 2012, 25′, From ‘The Speeches Series’, 2012-2013. 3 digital films. View of the Installation at “Bouchra Khalili”. Solo exhibition, CAAC, Sevilla. 2018 // Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier

JR: What is the relationship between these voices and “free speech”?

BK: I have been reflecting on Pasolini’s conception of “cinema of poetry” and its corollary “free indirect speech” for about 20 years now. Pasolini’s idea of free indirect speech in film aims to answer the question: in a film, when someone speaks, who speaks? Is it the character? The filmmaker? Or others who are not visible but nevertheless present through speech acts?

As a poet primarily committed to language and as a self-taught semiotician, Pasolini had to interrogate the essence of language and orality in filmmaking. He answers with the “free indirect speech” as a technique of equality: he who speaks, speaks for himself, speaks for the author, speaks for those who are absent, for those who cannot speak or can no longer speak. A multitude of voices merges, equally sharing the same platform.

Now speaking of my own work, the subjects perform their own speech and reflect on their own experiences. Such speech acts cannot be dissociated from language as a form of resistance: how to speak your own words and not the language of power? And when one refuses to speak the language of power, not only does one find agency, but also a voice that starts to articulate a collective one. It is no longer a voice alone, or a lonely voice; it articulates a collective voice from the singular.

Bouchra Khalili: ‘Living Labour,’ 2013, 25′. Color. Sound. From The Speeches Series. 2012-2013. 3 digital films. View of the Installation at “The Opposite of Voice Over”. Solo exhibition Färgkariken Konsthall, Stockholm, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier

JR: What motivated your move to Berlin? What do you make of its current political and cultural landscape?

BK: I was invited by DAAD-Artists in Berlin program and, as many of my fellow residents, I stayed. In the very first weeks of my relocation, I met Bonaventure Nkidung, Founder and Artistic Director of SAVVY Contemporary. For about 10 years, SAVVY has been doing an essential work reflecting on issues of decolonialism, offering thought-provoking exhibitions as well as platforms to various groups of artists, performers, activists, intellectuals. But leaving this burden on SAVVY’s shoulders is too comfortable for the Berlin art scene.

The Berlin and German art scenes are still very much Western art-oriented. And when those scenes look at art from the Global South, it is from a very conventional perspective: they stick to regional group shows, telling the history of the “modernities” from the Global South, but turned into a decorative pattern—nice wallpapers or vitrines—which eventually de-politicize the issues.

These very same institutions rarely acknowledge that “modernity” is a Western invention and that our modernity was essentially a matter of struggle for liberation and independence. If one looks at the extraordinary group conversations published in the Moroccan publication ‘Souffles’ (1966–1974), what was extensively discussed by North African and Sub-Saharan artists and intellectuals is how we could shape our own concept of “modernity.” And what they always end up concluding is that our modernity is a decolonial conception of art, philosophy, literature, cinema, and so on. In one phrase: a decolonial reality.

Bouchra Khalili: ‘Foreign Office,’ 2015, Mixed media installation: digital film, 15 photographs, 1 silkscreen print // Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier

Bouchra Khalili: ‘In Girum,’ exhibition view Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, 2019 // © n.b.k., photo by Jens Ziehe

JR: How did your recent project on the facade of nbk come about?

BK: The title of the piece, ‘In Girum,’ refers first to an apocryphal quote by Virgil and, of course, to a film and a book by Guy Debord: In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni. I always liked that palindrome a lot. When I was invited by nbk to propose an intervention on their façade, I started from their archives.

I found it interesting that nbk started archiving video at the very moment it was being invented as an art practice. In fact, many artists who were starting to work with video did not think that it could be archived, that their masters could be preserved and even restored one day. So I just started looking at the façade, and I remembered that palindrome. To me, it became the epitome of the archivists’ vocation: taking out from the fire what can still be saved.

More prosaically, a palindrome can be read on both sides. The sign above nbk shines at night. It operates as a warning sign: how do we find our way, collectively, in the middle of this wildfire in which we live?

Exhibition Info

NEUER BERLINER KUNSTVEREIN

Bouchra Khalili: ‘In Girum’

Exhibition: Nov. 23, 2019–Aug. 31, 2020

Chausseestraße 128–129, 10115 Berlin, click here for map