Interview by William Kherbek // Apr. 17, 2020

“Viruses are legible transmission, although you only know about them when they communicate with you,” or so runs one of the pithier apophthegms in Nick Land and Sadie Plant’s ‘Cyberpositive.’ Relatable content if there ever was such a thing, but if you’re feeling like you’re living through an accelerationist nightmare without the MDMA to cushion the blow, you’re hardly alone. The present transmission from Covid-19 to humans is getting more legible by the day, but legibility is only one part of a system of discourse. Human beings and microorganisms have been parts of each other’s stories since the beginning of the human species; indeed, long, long before it. It is only comparatively recently that humans have been interested in what might be communicated, or what the needs of our longest-standing interlocutors might be.

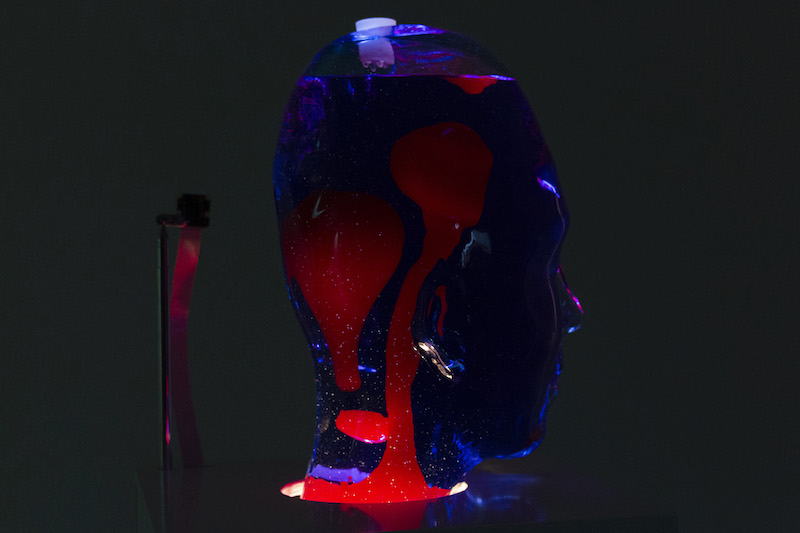

Jenna Sutela’s art has concentrated on the ways various microorganisms experience and impact the biosphere. From the poetic output of a bacteria colony used to power a computer to the creation of a pseudo-language based on the movements of Martian bacteria, Sutela’s work creates pathways for visualising, understanding and making contact with the countless invisible species that live around us and inside us. An exhibition of her work ‘I Magma’—which uses the lava lamp as a visual touchstone for an app-based oracle—recently opened at the Kunsthall Trondheim. We spoke to her shortly after the exhibition was closed to the public over concerns about the spread of Covid-19.

Jenna Sutela: ‘I Magma,’ 2019 in exhibition ‘NO NO NSE NSE,’ 2020, installation view at Kunsthall Trondheim // Courtesy of Kunsthall Tronheim, Photo by Aage A. Mikelsen

William Kherbek: How did your interest in the forms of interspecies or inter-organism communication you explore first develop?

Jenna Sutela: It started from a curiosity about the gut-brain connection, and also some left-cybernetics ideas about the brain—or the cranium—not being the limit of consciousness. I was really interested in Brits like Stafford Beer. Through my work I’m often trying to sense these other minds that live in the gut, for example, to communicate with the bacteria that regulate our thoughts and emotions, and our health and well-being, of course.

WK: In your performance ‘Many-Headed Reading,’ you ingest the slime mould Physarum polycephalum and the performance consists of an interpretation of the role of the agency of the mould inside you. Could you talk a bit about how you went about “thinking your way into” awareness and the thought-process of the mould?

JS: This single-celled, many-headed species of slime mould is also known as a natural computer, so my ingesting it refers to a form of AI where I’m letting the slime mould’s hive-like behaviour programme my own, or letting it speak through me. I guess with the idea of the slime serving as some sort paranoid critical agent helping me make connections that previously weren’t in me. That was the closest I felt I could get to it: eating it, ingesting it.

Jenna Sutela: ‘Many-Headed Reading,’ 2016 // Photo by Mikko Gaestel, courtesy of the artist

WK: Presumably this was a major shift in terms of the frames of reference you took into account, as mechanisms and output of perception in such a creature are almost certainly vastly different to the frames of reference humans tend to use.

JS: I think this is the key question for a lot of the work I’ve been doing recently. I’m very curious about things beyond the reaches of human reasoning, and I’ve tried to interfere with language and symbol (systems)—for example, by the ingestion of slime mould—and through computational processes in other works to try to sense the world in some other, more direct way, if possible, or from a non-Anthropocentric view, which is, of course, very difficult for a human.

WK: Your work ‘Holobiont’ uses the term, coined by Lynn Margulis, which describes the relationship of host organisms to other species living inside it or in significant proximity to it as a single ecological unit. In the case of the work the organism Bacillus subtilis is the focus of the narrative, which shifts from a radical interiority—the human gut—to a radical exteriority, outer space. Moving from one scale to the other involves a huge shift of perspective. Could you discuss your choice of this specific bacterium and why you felt it was the right protagonist for your film?

JS: The interesting thing regarding the gut microbiome is that maybe we can sense it, but we can’t see it. Our relationship to that bacteria is always somehow technologically mediated. The bacteria that is the protagonist of the ‘Holobiont’ video is an interesting example because it’s living in our guts, via probiotic foods, particularly the nattō fermented soybeans, but it’s also one of the most common species taken on space flights to test the limits of life on Mars, for example. It’s an interesting case of something existing in outer space—also maybe coming from there—and also in our guts. In ‘Holobiont,’ both of these possible habitats are explored and what’s really interesting to me is that we need this technological component to see them or hear them. The term ‘holobiont’ stands for an entity made of many species, all inseparably linked in their ecology and evolution. The video is calling for a move from traditional ideas of agency to thinking about agentic assemblages where human agency is bound up with bacterial agency. We’re as much bacteria as we are “human.”

WK: The recent work ‘nimiia cétiï’ builds on the notion of distributed forms of intelligence and technologies. It recalled in some ways your 2017 work ‘Gut-Machine Poetry,’ involving a SCOBY (symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast) and a computer. As so much of the AI discourse surrounds humans and AI and power, I was wondering if you had any thoughts about the ways in which non-human forms of awareness and intelligence might form relationships with machine cognition entities (and potentially vice versa).

JS: With ‘nimiia cétiï,’ on one hand it’s about getting in touch with the nonhuman condition of the computers that really work as our interlocutors and, on the other hand, it’s about how computers get in touch with the more-than-human world around them, and seeing what comes out of it. Ever since the Renaissance, most of the “intelligent machines” we’ve created have been used as the analogy of the mind, but the human mind is intuitive and too complex an organism to formalize; but perhaps there are other ways of looking at cognition, too, and other ways of looking at the machines, not anthropomorphising them too much.

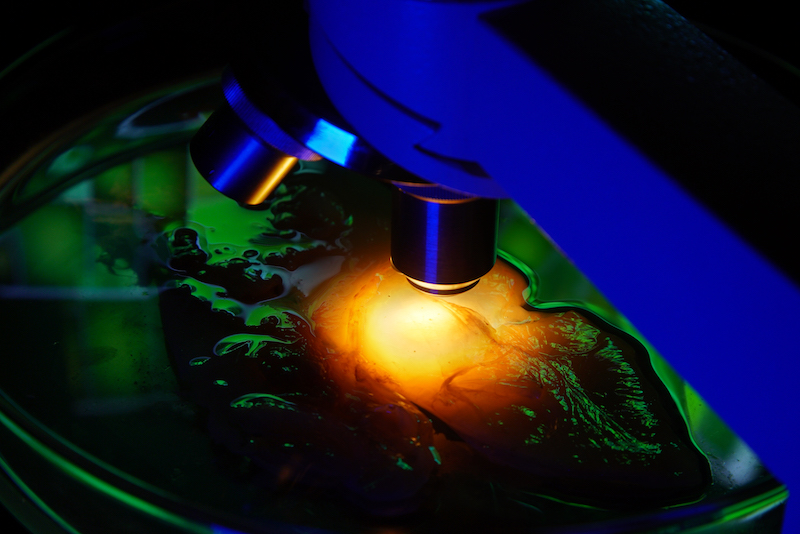

In ‘Gut-Machine Poetry,’ the idea was to think about intelligence as an embodied thing. I wanted to insert a gut into a computer, so I did it through this kombucha ferment that worked as a random number generator. ‘nimiia cétiï’ was a little bit of a smarter version of the GMP logic; there, the computer was seeing microbes under a microscope but, in this case, their movements weren’t used as a random number generator, but as a kind of score for organising things and creating this sort of Bacterial-Martian language, which I like to call it.

Jenna Sutela: ‘Gut-Machine Poetry,’ 2017 // Photo by Mikko Gaestel, courtesy of the artist

WK: Has the making of these works changed your way of viewing language as a tool of communication (though by no means the only tool)?

JS: You asked about the linguistic component in ‘nimiia cétiï,’ I found this late 19th century document of Hélène Smith’s Martian language. Hélène Smith was this French medium who was the first person to say that she was communicating Martian transmissions and interpreting them in a language. The linguist and psychologist, Théodore Flournoy, documented her séances in written form—it was never recorded at the time, of course, but it was documented—and he made this analysis that it kind of sounded like French, but it had an interesting structure, and I tried to gather everything that I found of Smith’s martian “deliveries” and then recorded it, bastardised it with my Finnish accent. Smith’s early “Martian” is considered one of the earliest documented forms of glossolalia, or speaking in tongues, which is another topic that has interested me. And so I recorded the language into small clips, and I let the computer use the bacterial movement as notation and organise it however it saw best. Each frame of the video connected to a little clip of the language and what came out was really surprising and really eerie, because the frames of the video are so short it was bacteria chorus that came out.

Jenna Sutela: ‘I Magma App’ // Courtesy of Serpentine Galleries / Ralph Pritchard

WK: Your recent work ‘I Magma’ uses lava as a vector for connections across forms of awareness and cognition.

JS: The work looks for ghosts in the intelligent machines of our creation. For example, the black box problem in machine learning has always been of interest to me, that sometimes it’s really hard to explain how an AI has come to its conclusions. ‘I Magma’ was inspired by the history of using lava lamps as random number generators. This happened at Sun Microsystems in the 90s, but, here, instead of randomness, I’m looking for patterns or signs or meanings in these blobs of liquid and colour in motion. Based on this input from the head-shaped lava lamps and inspired by the Internet Sacred Text Archive, as well as some Erowid trip reports, a computer is performing textual divinations based on the shapes that form.

WK: I feel like I would be remiss if I didn’t ask your thoughts on the current moment of Covid-19 inspired interspecies dialogue. Has your artistic work brought you any perspective on this particular moment?

JS: The current corona crisis is a moment where these invisible life forms are creating choreographies for us, and we’re very painfully aware of them. Even though we don’t see them, we sense them. I’ve looked into mostly what are called “Good bacteria” in my work, not viruses, but still it’s an interesting interspecies experience as well as a species experience where everyone in humanity is faced with the same condition in the same airspace.

WK: It’s an interesting moment in that it materialises what it means to be human in the most fundamental sense. We are susceptible to this virus because we are human, but it is also a moment of extreme “othering.” It’s easy to other a virus, of course, but all the talk of the role of immigration and borders in Covid discourse, for me, demonstrates the ways in which the moment highlights the absolute commonality of the human experience is giving rise to dynamics that attempt to find gradations in that commonality, on which to establish in-out group dynamics and hierarchies.

JS: This situation forces us to shift our subjectivity beyond anthropocentrism and individualism, forcing us to understand ourselves as being interconnected with the wider environment. Our position as the dominant species on the planet is being challenged, as well. So we really need to work toward creating thriving and interconnected ecosystems. The survival of the fittest narrative won’t do. It’s a terrifying and fascinating moment.

Artist Info

Jenna Sutela: ‘I Magma,’ 2019 in exhibition ‘NO NO NSE NSE,’ 2020, installation view at Kunsthall Trondheim // Courtesy of Kunsthall Tronheim, Photo by Aage A. Mikelsen