by Hannah Carroll Harris // Apr. 14, 2020

This article is part of our artist Spotlight Series.

Catherine Evans’ quietly confounding works are at once strangely familiar and beyond how we currently know and classify earthly matter. With a background in science, and then photography, Evans takes a considered, poetic approach to art-making in order to expose unexpected correlations between concept and form. Corporeal intricacies, like freckles and bruises, become markers of time, and heavy rocks become weightless cosmic forms in her interdisciplinary practice, which spans photography, sculpture and installation.

Catherine Evans, with ‘Standing Stone’, 2020, exhibition view at Galarie im Saalbau // Courtesy of the artist, photo by Piotr Pietrus

Originally from Australia and now based in Berlin, Evans engages in a research-led studio practice that investigates the intersection of human and geological timescales. Choosing her materials not for their transformative possibilities but for their inherent, immovable qualities, Evans turns to everyday objects like sticky-tape and carpet, subverting their utility to establish new, other-worldly associations.

For Evans, photography is not only a form of documentation but a process that underpins her practice—with light, shadow, composition and time all being key components to her working method. Refracted light becomes sculptural and shadows solidify to manipulate our sense of perception, as in her most recent work ‘Standing Stone.’ Occupying the expanse of an entire wall, rocks teeter, seemingly at random and with a sense of alchemy, atop pale pink poles that lean effortlessly against the wall: an improbable feat given the rocks’ heft. These curious minerals initially appear to be standing solo, though you soon realise that they are connected by softly shimmering beams. As light reflects off the surface of clear sticky tape adhered directly to the wall, the overall impression of an interstellar network forms.

Catherine Evans, ‘Standing Stone’, 2020, exhibition view at Galarie im Saalbau // Courtesy of the artist

Catherine Evans, ‘Standing Stone’, 2020, exhibition view at Galarie im Saalbau // Courtesy of the artist

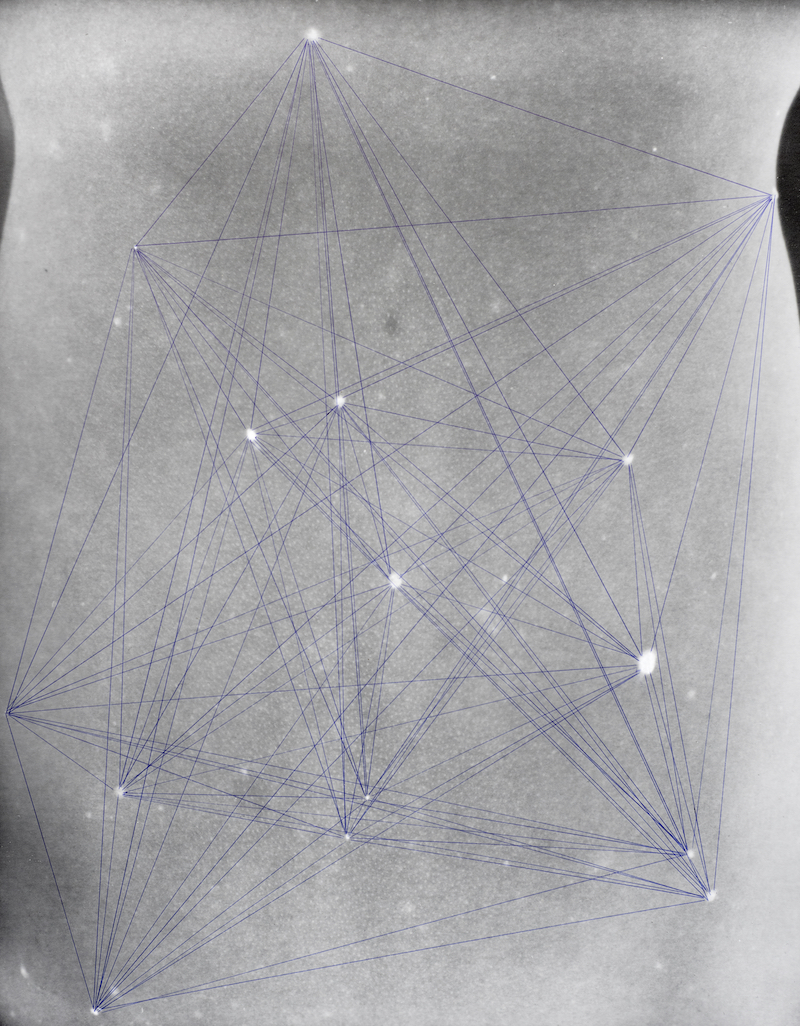

Originally exhibited at BLINDSIDE in Melbourne in 2014, the work has had several iterations. Most recently it was the recipient of this year’s Neukölln Art Prize at Galerie im Saalbau, where it was accompanied by a photograph of the artist’s own back. The colours of the small silver gelatin print have been inverted so that would-be dark spots and moles appear as bright white markers on a grey enigmatic background. These points of light are connected with simple ball-point pen ruled lines, like a star-mapped sky. The pattern is replicated on the opposite wall, as the rocks are plotted in a similar arrangement. This mirroring, transplanting fleshy formations in stone and rendering cosmic patterns with earthly matter draws parallels between our bodily state and a greater geologic time scale: simultaneously directing our attention from our corporeal experience in the gallery to the infinite ponderance of the universe.

Catherine Evans, ‘Constellation’, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist

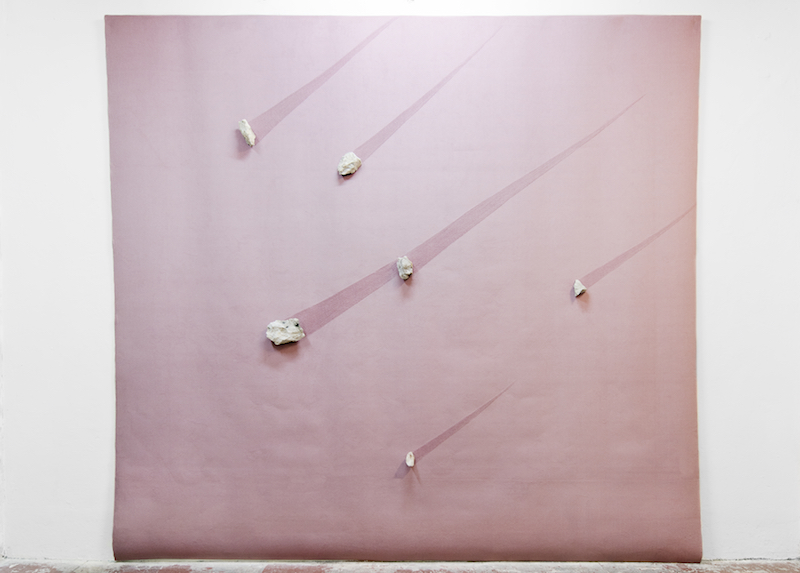

Viewing Evans’ artwork we become acutely aware of our bodies in space, whether through changes in shadow and light as we move around her installations, or the way in which she uses texture to situate us in relation to her chosen subject. Tactile muscle-memories are triggered in ‘Irrstern,’ an impossible constellation that transcends the material expectations of the sum of its parts, quartz stone collected from a Polish quarry and blushing pink carpet. Here, Evans takes two materials that would usually be found under foot and elevates them, installing them directly onto the wall for us to inspect their material intimacy: the roughly cut surface of the crystalline quartz pinned against the supple plush velveteen carpet.

This juxtaposition immediately magnetises, at once familiar and very much unexpected, conjuring images of far-flung star maps, but not like any we’ve ever seen before. These connotations come from the simple manipulation of the material, the quartz rocks seemingly fall from above as the carpet has been brushed against the direction of its pile to make it appear as though these rocks are plummeting comets, or as irrstern directly translates: lost or wandering stars.

Catherine Evans, ‘Irrstern’, 2017 // Courtesy of the artist

This illusion of movement is testament to Evans’ ability to take well-established conventions and shift them ever-so-slightly to create works that are reminiscent of some sort of taxonomic arrangement. Her work often borrows from museological display but subverts it in ways that make it hard to pin down, as our material associations warp, shifting our point of reference. Her rocks are chosen both for their aesthetic quality (the spots of lichen that have blemished the porous surface) or for their contained history (100-year-old granite bluestone that was excavated from the heart of Melbourne). Just as gemstones and archeological artefacts are preserved in museum collections, there is an inherent sense of the archival in Evans’ work, as the rocks themselves form a record of centuries of terrestrial time.

Evans’ repetition of the constellation motif is emblematic of her attempt to break things down to their basic form and build them back up to forge new connections and connotations. By borrowing and subverting from astrological, scientific and museological methods, her work defies pre-established taxonomic categorisation, forming its own language of material intimacy to trigger a re-thinking of the human in relation to the geological.

Artist Info

Catherine Evans, ‘Land Fall’, 2019 // Courtesy of the artist, photo by Matthew Stanton