Interview by Cristina Ramos // May 22, 2020

The shift from consumer aesthetics toward an understanding of agriculture and the rural(s) as a sphere for artistic research is the basis of Spanish artist Fernando García-Dory’s work. Combining locally-rooted durational projects (some of them 16 years long) and contributions to various art spaces and exhibitions internationally, he describes his practice as “continuing the genealogy of the landscape genre, with the pastoral as a subgenre, while problematising the often assumed conditions of formal representation, human alienation and power relations within it.” Interested in the harmonious complexity of biological forms and processes, his work addresses connections and cooperation in microorganisms and social systems in order to develop agro-ecological projects and actions.

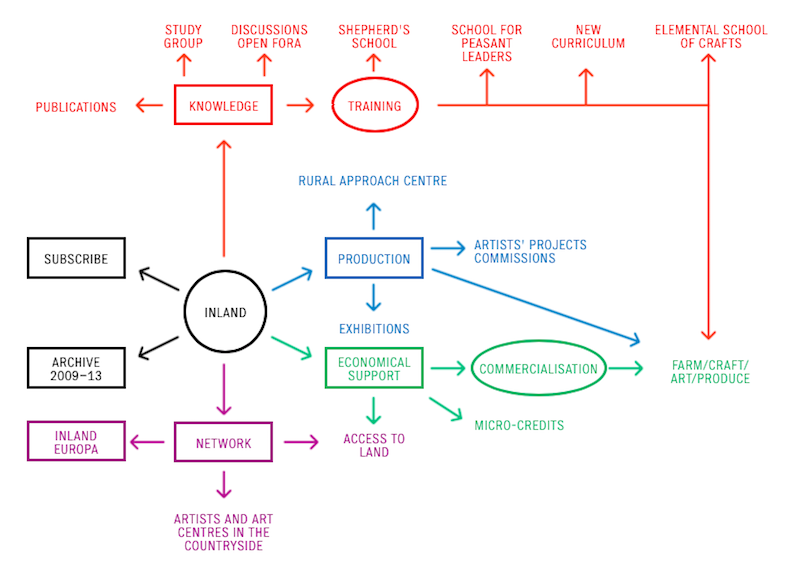

The materiality of García-Dory’s work is shaped by the seasons and the weather, by harvests, the migration of sheep and farmer’s ideas, to name a few factors. He’s also initiated INLAND, a collective para-institution that appears in different forms in different countries: they publish books, produce exhibitions and make cheese. They also advise as consultants for the European Union commission on the use of art for rural development policies, while facilitating the World Alliance of Mobile Indigenous Peoples (WAMIP) movement, associate of international farmers organization Via Campesina. We spoke to García-Dory about how he uses performative methods to inflect his socially engaged practice.

Fernando García-Dory: ‘Lament of the Newt,’ collective performance for Gwangju Biennale, 2016 // Courtesy of INLAND

Cristina Ramos: The rural landscape is often conceived as a place of tranquility away from the hustle and bustle of the city. However, boundless aspects of urban life are connected and dependent on resources, culture and production located within rural geographies. Many of your projects cultivate a place for artistic engagement with the dissolution of the urban/rural cultural divide such as ‘Lament of the Newt,’ part of the 11th Gwangju Biennale in South Korea, which took place in Hansaebong Dure, the city’s last rice field. The performance drew upon many socio-economic aspects of the region but also brought in concepts of time and living systems.

Fernando García-Dory: I first want to say that the rural is a form of expression of the relation our species builds with its environment, and culture is the tale we tell ourselves to make sense of that relation. After visiting Gwangju, I started thinking about the conflict posed by the urban tissue vs. the diversity of the ecosystems. The last rice field was located in a site intended to be transformed into a highway junction against the will of the local community. The field was home to diverse species, including wild newt (a type of salamander), a bioindicator of the good health of an ecosystem. Gwangju hosted a big scene of performative arts endangered by the dictatorship, but in the 70s and early 80s it flourished, and was called the ‘Little Theater Movement.’

The cultivation of the field required a large number of neighbours sharing the goal of its protection and developing a space for a living pedagogy on farming activities and scientific studies of aquatic microfauna. In this context, the artist has to be perceptive of the need to legitimate their stand, gain visibility and build something together that is exciting and creative. ‘Lament of the Newt’ took the rice field as a living theatre hall and started by drawing the field full of characters that would repeat an action situated in a future in which the field has been destroyed and the highway established. More than a traditional theatre play, the idea was to make a tableau vivant composed of simultaneous scenes. Instead of sitting and watching, the audience would walk through the field, accessing a story through those animated situations that included characters from a living tree, the Cloud People, the Rice People, the Biosecurity Authorities, the Car Fan or Kpop Trekkers.

Fernando García-Dory: ‘Lament of the Newt,’ collective performance for Gwangju Biennale, 2016 // Courtesy of INLAND

CR: How was the social process of developing the performance, from its inception until the presentation?

FGD: Around a hundred people took part in the preparations. We made it all—from the costumes with vegetal natural dye to the sets, sound pieces and texts. Even the libretto was illustrated by hand and riso-printed. The process lasted for four seasons, concluding just before the rice harvest celebration. We stayed at the site, cooking, learning, working together. The dialogue was so horizontal during the process that it felt more like a village organising a fiesta. We ended the last performance with a feeling in the group that went beyond doing something in common. They had made art in common and the rice field continues to this day.

CR: The rural landscape as a place for contemporary art may entail a slow mode of producing. How can this process be exhibited in a way that is representative, not-rushed and ecological?

FGD: I think that instead of thinking of rural landscapes as a place, we could consider the local as a context. In a city neighbourhood or a village, the scale of local interactions involves a durational engagement. Contemporary art under globalisation has privileged the opposite: fleeting programming, the self-referencing of the art world and spectacle. In ‘Lament of The Newt,’ I looked at a neighbourhood in that liminal space between the city and the countryside, with an urban design based in tower blocks and a limited sociability. I experimented with the idea of generating the mutual trust and bond of a, let’s say, medieval, commoning village. I like that you connected slowness and ecology… I think it is important that we keep that triple dimension of ecology that Felix Guattari proposed: not only environmental but also social and mental.

Fernando García-Dory: ‘Lament of the Newt,’ collective performance for Gwangju Biennale, 2016 // Courtesy of INLAND

CR: Commoning as a form of collectively approaching our past to build a sustainable future is one of the precepts of INLAND, a tentacular project that has been developed since 2009. How did it take shape?

FGD: INLAND started as an organisation to work on artistic processes, territory and social change. It has evolved into an arts collective dedicated to agricultural, social and cultural production. During the first period (2010–13), the idea was to open a field of practice that comprised an international conference, 22 artists-in-residence in the same number of villages across the diverse Spanish countryside and nationwide exhibitions and presentations. This was followed by a period of reflection and evaluation, launching study groups on art and ecology, and series of publications. The idea of the collective works in between a social movement or a start-up to open space for land-based collaborations, economies and communities-of-practice as a substrate for post-Contemporary Art cultural forms. INLAND also functions as a space for testing different notions of a possible future for eco-social sculpture.

CR: Do you think that the definition of the exhibition needs to be rethought in order to cultivate a more collective cultural practice?

FGD: We develop moments of sharing in our own terms. So more than a name, an “exhibition” is an act that involves a social, spatial and aesthetic structure. A choreography. Sometimes, it has a limited duration of a few days and it tries to build on the stories of what has happened, on a context. I think that more than a dismissal of the museum or exhibition space as anachronistic, we have to take it as it is, with its potentials and limits. I consider that we work over the territories with primary audiences. Not only people but also agencies in general (such as the agency of a highway and that of a newt, classified as endangered species) and often, we work with land-use frictions. And then, there is a secondary audience with whom we all share. Not just us as INLAND, but the process and its agents. There is an exchange, some spontaneous evaluation and feedback, a direct interaction. The exhibition as a mediation interface has a relative valence. If you like, none of those agents are really audiences in the conventional sense of passive receivers. There is quite a lot of making on-the-go, too.

This article is a part of our Features’ topic ‘Landscape’. The themes in this topic are inspired by the exhibition ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway,’ presented by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Berlin, and aim to spark a dialogue with its curatorial framework. The exhibition explores concepts of identity and home through intimate portrayals of the region’s landscape, both ecological and social, using a wide variety of media from sound and film to textile and sculptural works. A further emphasis of the contemporary works on display is the presentation of works by artists who belong to the Indigenous ethnic group of the Sámi. To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

fernandogarciadory.info

inland.org

Fernando García-Dory: ‘Inland’ // Courtesy of the artist