Interview by Elizabeth Schippers // June 09, 2020

A cascade of bones spirals down from the ceiling, creating a fluid motion reminiscent of a windchime. For ‘Spirals of the Pile’ (2018), the reindeer jaws, reused from Máret Ánne Sara’s previous pieces, are carefully stacked on top of each other, each piece thoughtfully and respectfully used and reused. These remains reappear in different installations throughout the years, directing the eye of the public towards the colonial practices present in Europe, which the affect Sámi people directly, and presenting a very physical consequence of colonial policy making on the Sámi community. Reindeer herding is vital to Sámi livelihoods, economically as well as culturally. ‘Gielstuvvon’ (2018) functions as a representation of this vitality. Hanging from the ceiling, the looped ropes almost resemble gallows, though the bright colors encourage the viewer to rethink this initial perception. If you look closer, you can see the marks that point towards its use as a lasso, the scuff marks of a tool integral to its users.

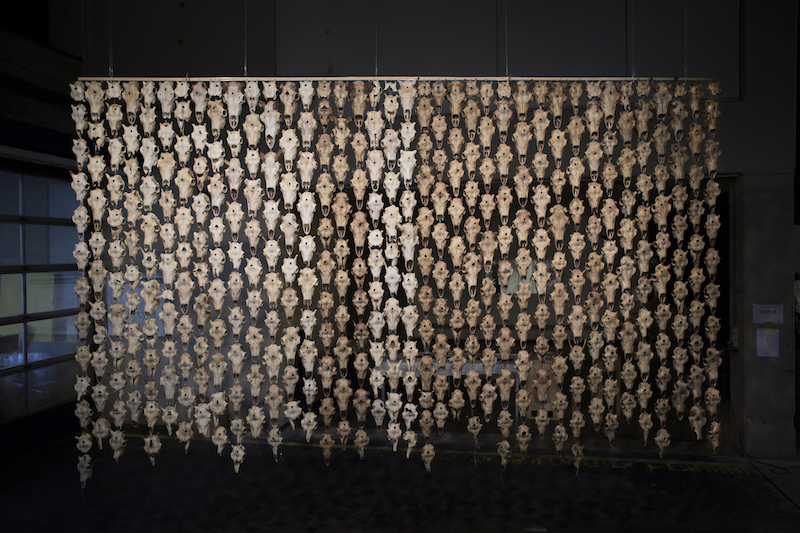

These pieces are a part of ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark,’ presented in Berlin in collaboration with the Norwegian Embassy. In her art, Sara frequently deals with social and political issues from the perspective of her shared history and identity as a Sámi artist. Her ongoing project ‘Pile o’Sápmi’ began as a reaction to the Norwegian government’s forced culling of reindeer belonging to indigenous Sámi herders. Sara created a pile of 200 reindeer heads, which she placed outside the Inner Finnmark District Court in February 2016 in support of her brother, who had initiated public proceedings against the Norwegian government to challenge the policies that actively harmed Sámi livelihoods. The pieces exhibited in ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark’ are a continuation of this debate.

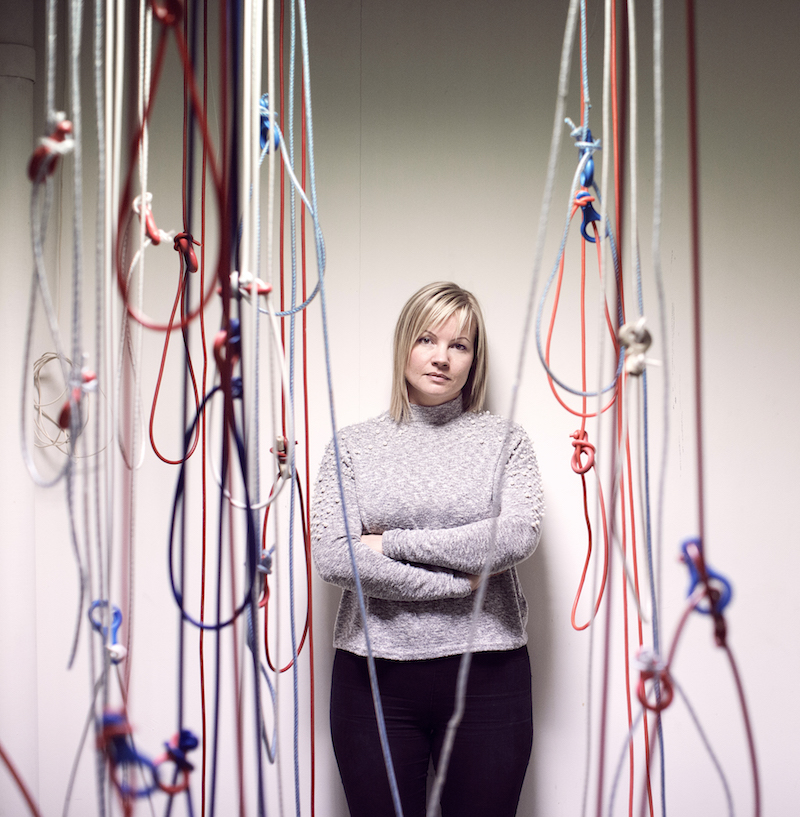

Portrait of Máret Ánne Sara // Photo by Marie Louise Somby / En terre Indigene

Elizabeth Schippers: For ‘Gielstuvvon’ (2018), you collected lassos used by Sámi reindeer herders to honour the personal stories and collective culture that reindeer herding represents. These lassos are an integral part of the livelihoods of Sámi people, however by bringing it to Berlin it is viewed outside of that context. How does your work translate as it takes this journey?

Máret Ánne Sara: This is a very interesting question. This is something that I’m always curious about, and I think it is a new but highly relevant question for most indigenous artists, now that indigenous art seems to gain more attention in the Western art scene. How do you explain, how much do you explain, and how would this work be read outside of its original context? For instance, for someone who doesn’t have any type of knowledge about how they are used or in which context, the lassos can have a strong resemblance to the gallows. What does the piece mean, then? It’s very difficult for me to answer on behalf of others, but it’s definitely very interesting to go to other cultures and regions and then debate, to see what this art piece means in different places. For instance, I’m invited with this piece to North America, and the history of this specific area and the use of gallows in this harsh historical context is something to be very cautious about. It needs to be considered with respect. So these are issues that I debate with curators and galleries at all times. It’s very interesting to see what the piece will mean and what it will speak to here in Berlin, in light of the history of Berlin, of Germany and the people there.

However, I would also like to stress that the lasso, as I know this tool, and how it functions, does not necessarily instantly resemble a noose for me. The specific shape that it hangs in is the natural shape of the lasso. It just happens that it has this connotation, as an extra layer, in the context of this piece that I’m working on.

Máret Ánne Sara: ‘Gielastuvvon,’ 2018 // Photo by Libor Galia

ES: You have mentioned that ‘Gielstuvvon’ (2018) is a more personal approach to your ongoing political art project, ‘Pile o’ Sámpi.’ How does ‘Gielstuvvon’ (2018) constitute itself as a continuation of this debate?

MAS: I made ‘Gielstuvvon’ at the very end of 2018 and by then we were involved in this political and legal struggle for six, nearly seven years. When I was working on this piece, we received the final notification from the government that they would not respect the UN Human Rights Commission in this matter and that they would activate the forced culling of our reindeer herd regardless of our appeal to the UN. So, at this point, I felt really helpless against the system. We have tried to follow all steps that are involved in taking part in the democratic system, but this system has let us down. When speaking of a personal approach, I think dealing with the responsibility of people’s mental well-being was very central for me, because when executing these systematic assaults, it seems that the mental health factor of human life is completely lost in the whole case. No one in the positions of making laws and deciding the rules for our lives is considering and taking responsibility for how this is affecting our lives on the mental health level.

I was reading quite a lot of academic research on the topic at the time, and it seems to be a global situation that indigenous communities suffer much higher rates of suicide than non-indigenous people in the same areas. The Sámi people are no exception. We have had quite dramatic numbers of suicides in the south Sápmi region and on the Swedish side of the Sápmi region. And, amongst the people committing suicide in the Sami population, the statistics show that young male reindeer herders are most vulnerable to this situation. And the explanation is the multiple stress factors, such as land issues, social issues that are part of colonial history, a lot of racism on a personal level in society. There are political fights that you are standing in the middle of, as well as economic issues. And then you have, of course, the structural abuse that I’m addressing, that comes through legislations and politics and so forth, such as the forced culling. This comes as a new, very drastic layer upon these stress factors, on a very small minority population that is already under quite dramatic stress for many different angles in society.

Máret Ánne Sara: ‘Pile o’ Sámpi,’ February 2016 at Inner Finnmark District Court, Tana // Photo by Iris Egilsdatter

And this is why I feel that governments and the system itself is really not taking any responsibility. In my area, in Guovdageaidnu, which is sort of the central Sápmi area, we have had, in my opinion, a psychological and mental protection, in the sense that we are a majority in this society. And this is the only place in the world, my town and Kárášjohka, where you can find Sámi people in the majority, where you don’t necessarily have to deal with all of these stress factors on a daily basis. For instance, going out to stores or banks or official offices, you have Sámi people working there, so they have, naturally, a cultural understanding.

But this forced culling, the system of the forced culling, is very cunningly made up. They have put people up against each other, creating a lot of competition between reindeer herders internally. When they activated this culling, they called it a practice of “inner self-determination”. But what this actually meant was that the government had decided already how many reindeers were to be slaughtered in these different areas, and our “self-determination” was to sit and quarrel with each other about who was going to slaughter and who was going to be spared. And, of course, if you are dealing with issues concerning your financial future, your culture, your heritage and your children, which are all connected to the reindeer herding livelihoods, then it’s a very complicated issue, and it’s created a lot of stress and wounds in this small society that is very much dependent on cooperation.

My theory has been all along that if our community is destroyed from within, because of these conflicts that the government is forcing upon us, then our mental well-being becomes even more fragile. So this piece has a personal level and a collective concern.

Máret Ánne Sara: ‘Pile o’ Sámpi,’ 2017 installation at Documenta 14 // Photo by Matti Aikio

ES: With your work ‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ (2016), you perform an artistic trial against the society that has failed you, whose decision to enforce a culling of reindeers belonging to indigenous Sámi herders led to a cultural and economical trauma that was inflicted on your community. Where has this trial led you? How do these experiences take form in your work?

MAS: It is very hard. I am still struggling with what happened on a personal level and I think that is very much reflected in my art. With my current pieces I am very much working with the body itself. I’m working on this jewellery collection, and ‘Gielstuvvon,’ and so forth. So it’s more about how we as individuals or humans carry these issues in our bodies, and how it is weighing so heavily without anyone being able to see it.

For now, we’re still waiting for a reaction from the UN Commission of Human Rights, but I don’t know, I think I personally have lost faith in the system. But what I have gained is faith in people. During this process I’ve seen the power of engagement, of people who really care. I’ve seen that we actually can make a difference. Even though we weren’t able to change the system, we have planted a seed for a change in the future by creating awareness and demanding fairness.

Máret Ánne Sara: ‘loaded -keep hitting our jaws,’ 2018 // Photo by Máret Ánne Sara

ES: This project has since led to an interdisciplinary art movement. Can you tell us about that?

MAS: From the beginning I have been quite open with this whole project, inviting in artists based on their own commitment and interest to elaborate on these topics. ‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ brings up such a broad discussion, which leaves a lot of space for other artists to individually work on these topics, but with the aim of creating a bigger debate that is connected. Some artists have made several songs about it, we have had guerrilla or street theatre performances coming from this process and several independent art pieces. It has just been my way of working, to be very generous with the ‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ name and concept, so that it is up to people to engage themselves in a way that they feel is relevant.

Of course, the other thing is the fact that I’ve arranged very complex and big artistic happenings for each trial, so in Tana, for the district court, I had 10 other artists joining in. At that stage there were not many new productions, but I invited in artists that already had work that was relevant to the court case in a broader sense, with regards to, for instance, the mental health issues I talked about. One of my colleagues made this beautiful dance movie, which is dealing exactly with this topic. The other one that I remember quite clearly is a documentary about how national laws took away all the rights of the River Sámi people. We can look at similar cases and learn from history, rather than constantly starting from the beginning. This is the philosophy that I’ve had when I invited in artists. I had over 20 artists coming to Tromsø, and we took over the public stage of the city for the two days that the trial was ongoing. In Tromsø we also had a street theatre performance specifically made for Tromsø and this event. For the Supreme Court in Oslo I took the flag with the 400 reindeer heads, and I hung it up outside the Norwegian parliament. There, too, I had invited a lot of other Sámi artists and we had exhibitions and talks, and so forth, but as we could hardly take over the capital city, the strategy had to be different, so this is why the ‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ piece and the location itself had a lot of the focus.

I’ve been working very much in dialogue with other thinkers, not only artists, but also people from the academic field, the legal field and so forth. If we have all of the different fields debating and thinking critically, that can activate some change. As a single person, I can hardly do that kind of thing with one art piece.

Máret Ánne Sara // Photo by Per Heimly

ES: ‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ actively changes the landscape of the colonial architectural structure by means of displacement. By placing Sámi reindeer bones in front of the Norwegian Supreme Court, a dual landscape is created. Can you elaborate on the conception of landscape for Sámi people as opposed to colonial practice?

MAS: When I’m listening to you formulating this question, what becomes most central for me is the spirit and energy of land, animals and life. For me, these bones have a very strong energy. When constructing the first pile in 2016, I was astonished by how powerful this energy was, because these were real heads, of animals that were living and wandering among us. And when I watched this first piling it was still in a familiar setting, it was on Sámi land, not so unfamiliar. But coming to Oslo it becomes even more dramatic, from my perspective. This colonial violence that I am addressing, that is hidden behind neatly and cleanly written laws and paragraphs, is much harsher, is much more apparent. It was very important to highlight these oppositions, this violence. It was a shame that almost none of the parliament members came out: we had invited all of them to join us outside of the parliament for a few speeches. I had invited the president of the Sámi parliament and the leader of the Sámi Reindeer Herders Association in Norway, as well as various artists and activists who were hunger-striking on the same spot 40 years ago, so very powerful and important voices. But no one came out to listen, except two of them, and one—Torgeir Knag Fylkesnes—actually spoke publicly in support of our situation.

‘Pile o’ Sámpi’ was a very difficult and strange experience, but I am still a little bit shocked that we managed to do that, that we managed to execute it. The fact that we did it is, for me, also evidence of how important this is for me and how strongly I, as an individual, feel about life and this matter. It is not just about a line of a pen that some politician or bureaucrat is making in his office. Every stroke of that pen is affecting our lives, our souls, our everything.

This article is a part of our Features’ topic ‘Landscape’ and is presented in collaboration with the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Berlin on the occasion of their exhibition ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway,’ in which Máret Ánne Sara is a participating artist. The exhibition, curated by Sabine Schirdewahn, explores concepts of identity and home through intimate portrayals of the region’s landscape, both ecological and social, using a wide variety of media from sound and film to textile and sculptural works. A further emphasis of the contemporary works on display is the presentation of works by artists who belong to the Indigenous ethnic group of the Sámi. To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Royal Norwegian Embassy

Group Show: ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway’

Exhibition: June 02–Oct. 03, 2020

nordischebotschaften.org

Fellehus, Nordic Embassies, Rauchstraße 1, 10787 Berlin, click here for map