Interview by Elizabeth Schippers // June 19, 2020

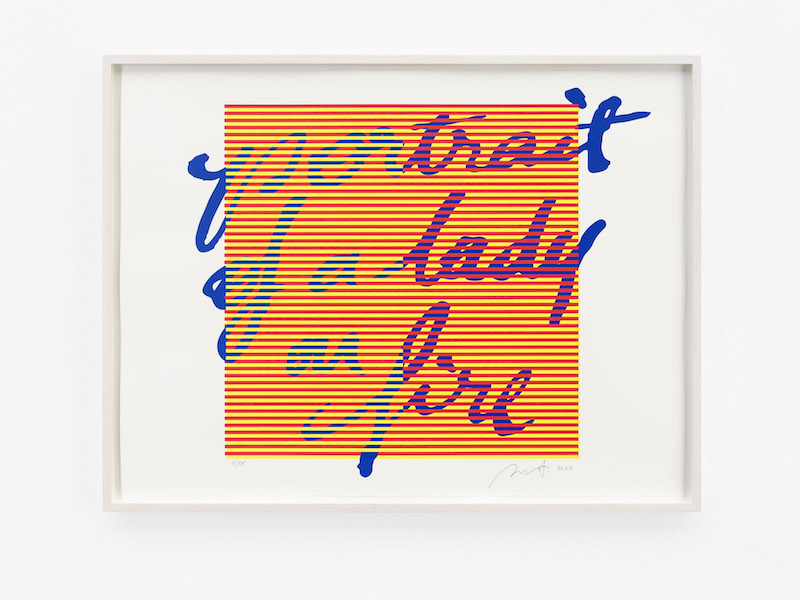

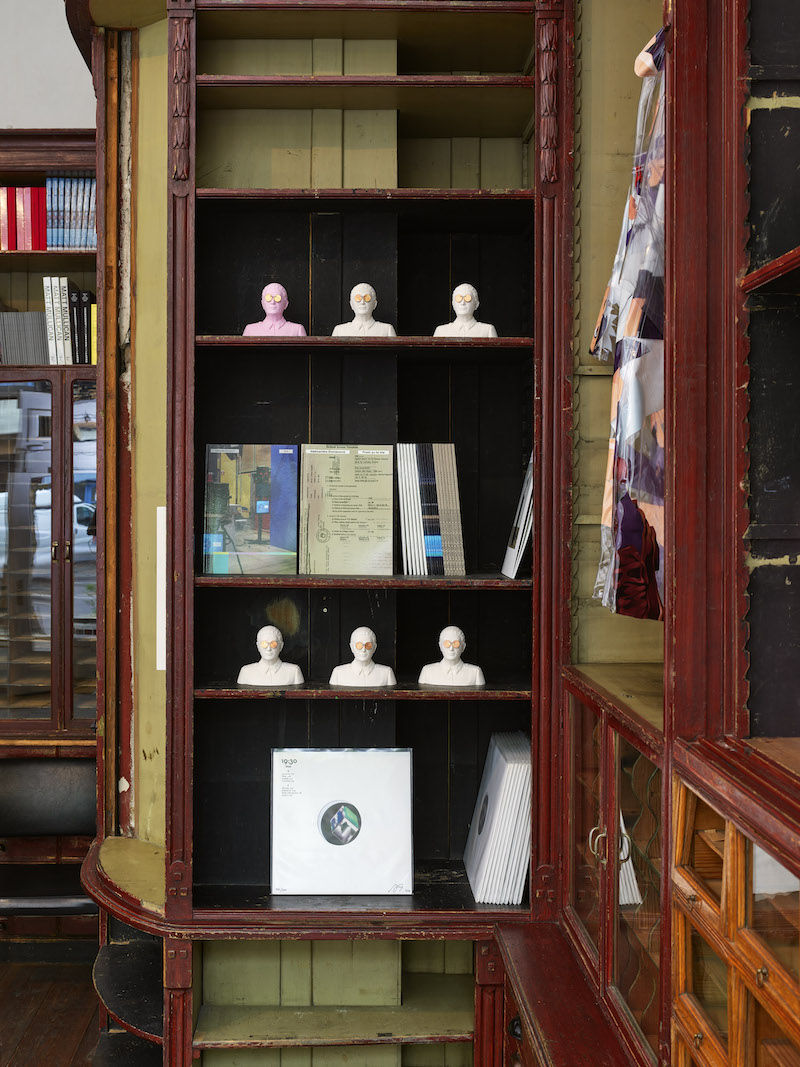

In one corner of the exhibition space, the walls are covered with prints of dots: overlapping dots, intersecting dots, eyes looking the visitor up and down, meeting our gaze. The prints also include adaptations of the text from the movie poster for ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire,’ a film that engages with the gaze in unprecedented ways, subverting the male gaze and exploring the potential for a different kind of looking. On the other side of the exhibition space, we are challenged to further explore the ways in which we look, not only at the present but, similarly, at history. A queered bust of the former Yugoslavian president Tito and miniature versions of the ‘Belgrade Hand’ and the ‘Bubanj Fist’ challenge the viewers perception. Aleksandra Domanović’s interest in friction, slippage and connections between seeing and perceiving are central to her most recent exhibition, ‘Edicije’, curated by Carson Chan at Klosterfelde Edition.

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Edicije,’ installation view // Courtesy of Klosterfelde Edition and Aleksandra Domanovic

Elizabeth Schippers: An overarching theme in your work is the exploration of feminist and cyberfeminist contributions to the development of art and science. How do these theoretical concerns figure into the process of creating your works, specifically the hybrid/cyborg sculptural works?

Aleksandra Domanović: It comes from my early interest in the online world. The internet is able to both cross national boundaries while reflecting aspects of the state. For example I made a work about the abolition of .yu (the top level country code domain of Yugoslavia) because I was fascinated that the domain kept on existing even 10 years after the country it stood for had disappeared. I was further intrigued as I found out that there were two women—Borka Jerman Blažič and Mirjana Tasić—that led the early internet implementation and administered the .yu domain in Yugoslavia. Borka was the one that told me about the so-called cybernetic hand from Belgrade, and I’ve used it as a “shell” for many ideas in my sculptures.

Taking a feminist position should not be seen as an extraordinary feature even though any artwork that seeks to contribute to larger discussions should naturally see the need to take feminism seriously.

ES: Another important concern of your work is the circulation and reception of information and images, specifically as they shift meaning traversing different contexts and historical circumstances. How does this ongoing concentration translate to the current exhibition at Klosterfelde Edition?

AD: Circulation and reception of information is something that was important to my work. It still is but it has also evolved, shifted focus. The silkscreen works in this show look at how reception is always connected to interpretation. As Carson Chan, who curated the show, put it: “It’s about the tension between seeing and perceiving.”

One of my projects I keep returning to is the queered Tito, Yugoslavia’s former president. First I supplied my 3D-modeler with images of Tito from the internet, images of his face from all possible angles and ages. I asked the modeler to make a bust of Tito, not based on any specific existing photo but a generic bust. After that was done I asked my modeler to feminize Tito’s features, but still keep him in uniform. So I have two busts now. I mostly only exhibit the queered version and people think that is how Tito actually appeared, they don’t see what I have done. But when I exhibit images of both busts together, the difference is obvious.

In the new silk-screens the tension between seeing and perceiving is performed by the viewers themselves. What they think they are seeing is not really true, it is created in their perception.

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Portrait (Mesing)’, 2012 // Courtesy of the artist

ES: ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ (2020) is a love story between two women and examines the female gaze especially as it relates to the portrayal of sexuality and sensuality. Adèle Haenel, one of the lead actresses, describes the film as representing an under-portrayed perception of sensuality, in which focus is placed on the relationship between the two women. In this way the interpretation of sensuality in this movie constitutes a critique of the predominant male gaze. How does your work engage with this discourse?

AD: Just like the story of the film my prints are about looking. I’ve been fascinated with the way different colors affect each other since I was taught color theory at school.

The intimacy between Marianne and Héloïse in the film builds from afar, through the gaze. They are looking at each other and we are looking at them. Paradoxically, the entire film is premised upon the male gaze. Marianne (the painter) is commissioned to paint a portrait of Héloïse for her potential male suitor in Milan. If he likes how she looks, he will marry her. Mid-film we see a man sitting in the kitchen while he is eating. He’s the only man we get to see inside the house and only for a moment. His presence alone is jarring.

There is a scene in the movie when the two protagonists have sex. Instead of showing the actual act the director had them finger each other’s armpits. In the starting shot of this scene we perceive it as an act of genital penetration, only when the camera zooms out do we see what is actually going on. This extremely sensual scene was achieved in a way that was non-revealing and comfortable for both actresses as well as the crew.

The film examines the female gaze from many angles, not just through sensuality or sexuality. There is a scene with a baby lying next to the maid on the bed as she is getting an abortion. I was wondering what the baby’s gaze is seeing. Later that night, the three women recreate the abortion scene as a motif for a painting. At play here is a feminine gaze that sees through the lens of scientific reason and pro-choice ownership of one’s own body.

Aleksandra Domanovic: ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire,’ 2020, Silkscreen print on paper, 60 x 80 cm // Courtesy of the artist

ES: How does this translate into your silkscreen works?

AD: In my new silkscreen works, I explore these dynamics through optics. The Bezold effect is an optical illusion, named after a German professor of meteorology, Wilhelm von Bezold (1837–1907), who discovered that when small areas of color are interspersed, a color may appear very different depending on its relation to adjacent colors. One color can change how we perceive the tone and hue of another. The colors themselves don’t change, but we perceive them as altered. I achieved this with horizontal lines that weave themselves over or under the motifs in the prints. For the motifs I used either two dots (a rudimentary depiction of the eyes – the gaze) or I used the text from the movie poster (‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’).

I was wondering how a slight shift of context can make us perceive the exact same thing so differently. For example, I made a print with two identical red dots over interlocked blue and yellow lines as a uniform background. One dot is overlaid with the blue lines and the other with yellow. The dot overlaid by blue lines looks 100% magenta and the one overlaid with yellow lines looks completely orange, even if we come very near. Our eyes are built that way.

If this film were shot in the exact same location with the exact same cast and plot, but through a male gaze, it would have been a completely different movie.

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Edicije,’ installation view // Courtesy of Klosterfelde Edition and Aleksandra Domanović

ES: ‘Edicije’ combines the pieces on the ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ (2020) and works like ‘Bubanj Fist’ (2020), ‘The Cybernetic Hand from Belgrade’ (2020) and ’19:30’ (2014). What is the relationship between these pieces?

AD: ‘Edicije’ means “editions” in all of the former Yugoslavian languages. The show is divided into two halves thematically and in the way it is installed. One half of the show riffs off my older works, which I reworked into editioned pieces. For example, I have miniaturized the ‘Belgrade Hand,’ a motif I used in my work since 2013, and made it into a necklace pendant. I wanted to do that for a long time: to realize all these ideas I had on the side of almost every bigger project that I’ve made. Same goes for ‘Bubanj Fist,’ which was a large-scale public sculpture I made for the 2012 Marrakech Biennale, the so-called “Monument To Revolution” that took after Ivan Sabolić’s Bubanj Memorial in Niš, Serbia. The Marrakech piece was 6-meters tall and was destroyed a year or so after the show. I wanted to make a smaller version of it as a keepsake, and I’ve kept the 3D model I made at that time to show the builders in Morocco. As I’ve mentioned, I have queered a bust of Tito many times in the past. For one version, I added an earring to it, this time I’ve added glasses made out of one cent Euro coins, following the pagan tradition of putting coins on the eyes of the deceased. All of these works and many more are installed in one half of the gallery. The other half of the space is taken up by the new ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ print series. The bridging piece between the two halves is the ‘Disney Letter (remastered)’ installed in the middle of the space. It is an actual letter from 1938 I found online and redrew. In it a young woman is being rejected for a job of an animator at Disney. They write to her: “Women do not do any of the creative work in connection with preparing the cartoons for the screen, as that work is performed entirely by young men.”

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Edicije,’ installation view // Courtesy of Klosterfelde Edition and Aleksandra Domanovic

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Monument to Revolution’, 2012 // Courtesy of the artist

ES: This exhibition includes ’19:30’ (2014), for which you collected the various intro-themes to former Yugoslavian nightly televised newscasts and asked DJs to transform them into remixes. How do you think this warping of sounds affects the way that the audience perceives this piece of Yugoslavian culture?

AD: I’m from the generation that experienced the break up of Yugoslavia during my early teens. It was about 1995 that the influx of techno music from the West finally reached, what were by then, ex-Yugoslav republics. I can’t remember ever before, or after, hearing something that was so different, so profoundly unlike any other music I had heard before. But the main characteristics of techno music—extreme repetitiveness, use of sequencers, synths and drum machines—were formally not far off, and perhaps symbolically conveyed, in the rhythm of the news delivery and stylistic direction of the news intro-themes.

For me, techno and news music make total sense together and not just musically but also politically. I recall the post-war techno craze as something that brought us together again, if only for short moments of pleasure. There was a genuine feeling of community and lack of violence at parties. The rave scene also had a liberating effect in terms of emotional awareness, mental literacy and gender relations. New patterns of public interaction were made possible. Young people traveled to and beyond the borders of the newly formed republics for raves. We started to discover the neighbouring countries ourselves, as the subject of Yugoslav history and geography had been dropped from the school curriculum.

The ’19:30′ project has several manifestations. It is a website, a two-channel video, a series of techno parties and a double album on vinyl. In ‘Edicije,’ I am showing the two records, one with all of the original intro-themes of Yugoslav news, and the other with selected remixes of the former. When non-Yugoslav people hear these tracks they don’t get a trip down memory lane like I do, but they still dance to them. They might recognize the DJs that have made the remixes and they might hear a bit of Serbo-Croatian or Macedonian spoken in the background.

ES: How does that translate to the tendency of images and information to shift meaning as they circulate, specifically regarding the ways in which image culture and information flows have formed the postwar environment of former Yugoslavia?

AD: The history of Yugoslavia has been interpreted from every former republic in its own way, every individual sees it slightly in their own way. I experienced the break in the official interpretation where practically overnight the stories they told us at school were swapped with new narratives. Not even past events are fixed entities. Not only can we change our futures, we can change our history. In some cases this is called revisionism, in others interpretation. Ultimately, it’s about how the world, its history, our own stories within it are open to the potential and dangers of interpretation.

Exhibition Info

KLOSTERFELDE EDITION

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Edicije’

Exhibition: Apr. 30 – June 27, 2020

Potsdamer Strasse 97, 10785 Berlin, click here for map

Aleksandra Domanović: ‘Edicije,’ installation view // Courtesy of Klosterfelde Edition and Aleksandra Domanovic