by Alison Hugill // Aug. 4, 2020

Fannie Sosa is an afro-sudaka activist, artist and scholar whose work focusses on pleasure and its transmission as a radical act of resistance. In 2016, they launched ‘A White Institution’s Guide for Welcoming Artists of Color* and their Audiences’ (aka ‘the WIG’) to counter many of the ongoing problems white supremacy has posed, specifically for Black artists and artists of color working within largely white-run institutions. With the WIG—which has been used by over 200 cultural institutions around the world to better their equity practices—Sosa presents a much-needed tool for dismantling “white supremacist patriarchal capitalism” in the art world, explaining that the cultural production of Black artists and artists of color “is capitalised on, while our bodies, well-being and communities are still expendable. Consumerism from the other side of the barbed wired fence is extractivism.”

One of Sosa’s most recent projects, created in collaboration with their artistic partner Navild Acosta, reflects on the disparity in rest (the “sleep gap”) between Black and non-Black people, and how fatigue has been used over centuries as a tool of white domination. Acosta and Sosa’s sculptural installation and curatorial initiative ‘Black Power Naps’ seeks to reclaim idleness and rest as power. We spoke to Sosa about how the WIG and the ‘Black Power Naps’ projects form part of a wider critique of structural and institutionalized racism.

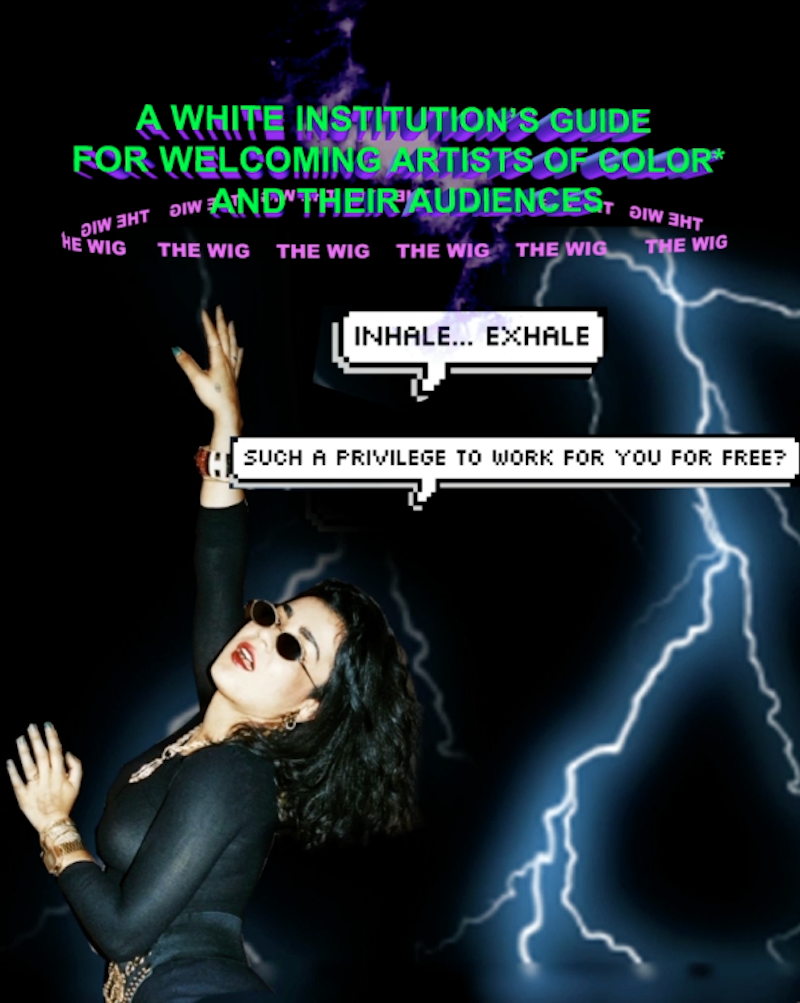

Fannie Sosa: ‘A White Institution’s Guide for Welcoming Artists of Color* and their Audiences,’ 2016, Image featuring Fannie Sosa, text by Fannie Sosa, visual elements by Tabita Rezaire in collaboration with Fannie Sosa // Courtesy of the artist

Alison Hugill: As the catalyst for writing the WIG, you’ve described some of the violent experiences you (and many other Black artists and artists of color) have encountered both in and en route to institutions worldwide. Can you talk about the ways in which this Guide has helped you to formalize the support needs of your community?

Fannie Sosa: I had never seen a document like the WIG before and I do think it was groundbreaking because it merges theory with practice. How do we actually make anti-colonial theory practical? What does it look like? We apply it to a very specific set of transactions, those between the white institution and the artist of color at the moment of booking a new job.

Every type of proposal coming from an institution that doesn’t have a reflection on reparation and doesn’t contribute to our wellbeing, rather than just extracting a product, is part of the structural and individual problem. White individuals within the institution do have a responsibility. It reminds me of the Ally vs. Accomplice confusion that Navild [Acosta] always talks about. White people as individuals have spaces, little windows in which to commit crimes. The real work is about those crimes, about defying justice as it currently exists. A lot of people just don’t want to break the law for us. They don’t want to put themselves on the line. When I say breaking the law, I mean the written and the unwritten ones: there are so many unwritten laws that regulate the transactions we have with the white institution. The WIG is about saying everything you think is unacceptable, or criminal, or beyond the scope of “professionalism” is the work.

AH: Have you seen a difference in your own interactions with institutions since publishing and disseminating the WIG?

FS: It’s still happening. Ninety percent or more of the email chains that I have with institutions are still traumatizing, or triggering, or just a lot of labor. But I feel like I’m starting to get an influx of emails from people who are in touch with the WIG or the thoughts around it and I do see a difference. For example, in the way you approached me compared to other journalists or writers who want to pick my brain or to interview me. It’s very important to me that people are really clear about what monetary transaction there could be. It was important that you understood why you would want to give your fee to me, when you are also laboring. It’s a train of thought that I am missing not only from institutions but from white people in general.

I keep seeing white people going to protests. I see white people posting pictures and sharing information. Okay, but that is not the work. You need to make available resources: money, time, access, space. White people are abundant in at least one of those resources, for sure.

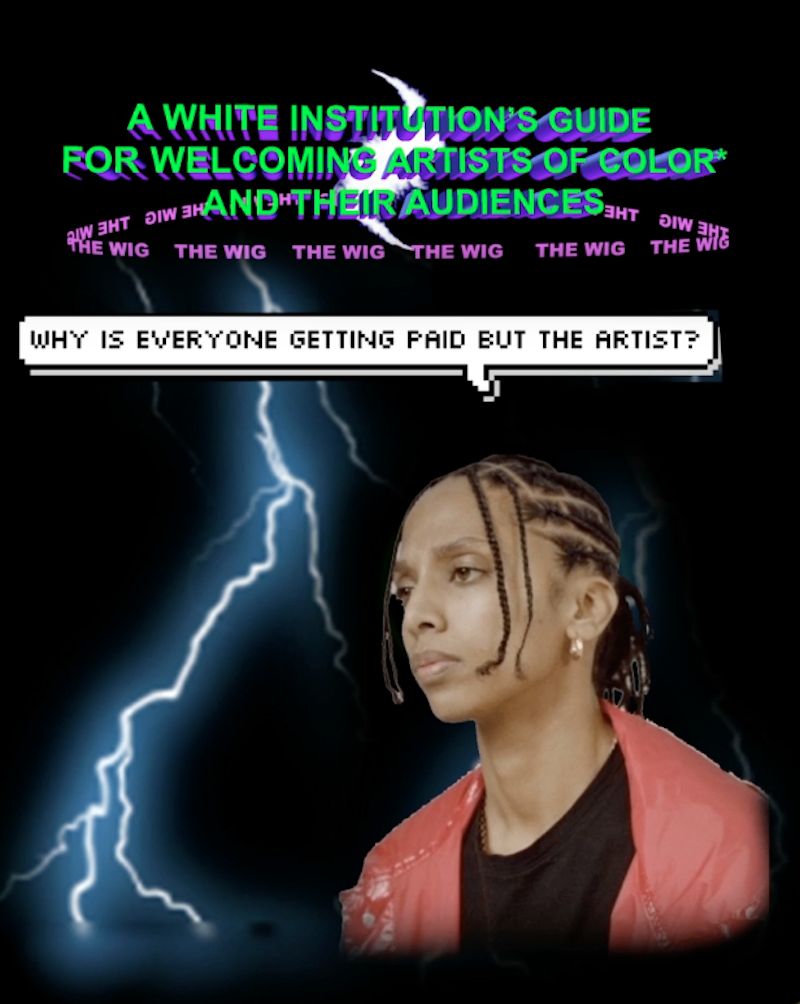

Fannie Sosa: ‘The White Institution’s Guide for Welcoming Artists of Color* and their Audiences’, 2016, text by Fannie Sosa, visual elements by Tabita Rezaire in collaboration with Fannie Sosa // Courtesy of the artist

AH: In the WIG you introduce the term “extractivism” to talk about how white institutions most often approach the cultural production of Black folks and people of color. Can you say more about that concept?

FS: Often, the approach that white institutions have toward our work or cultural production is extractivist because it only pays for that production or object. In any other situation where labor is acknowledged, you pay for that labor, not just the object. You pay for the hours of preparation, the research, the expertise, for the fact that we are offering a perspective other than the one that is already present. The thing that has cost me the most is being made to feel like I have to be grateful for being at the institution, and at the same time almost not even being able to get there, because I’m not ushered in. I’m supposed to do an obstacle course to get there, just in the brink of time, and then I’m supposed to be composed like everyone else who just walked in there from a taxi.

Extractivism is about extracting precious minerals from the ground. And that is what the white institution does to artists of color. It hollows us out. And we do actually die. We live our lives maimed, and I really think that that needs to change. We live in an apartheid: When I see white artists welcomed into the institution, there is a very different care for their lives and for their wellbeing. In order to not be extractive, you have to care about the person on an individual level, too.

Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa: ‘Black Power Naps/Siestas Negras’, installation view // Photo by Xeno Rafaél

AH: How do you feel about the fact that many white institutions are now scrambling to implement some of the changes you have identified in the WIG, and which Black folks have been fighting for for ages, now that the Black Lives Matter movement is gaining a different kind of momentum?

FS: I don’t trust it. And, at the same time, I have to remain hopeful. I fight a lot of bitterness. It’s part of why we age, why we die, why we get sick. You think: “I said this years ago, and I said it for free on Facebook. And now it’s a fucking seminar at a university.” We know. We can tell.

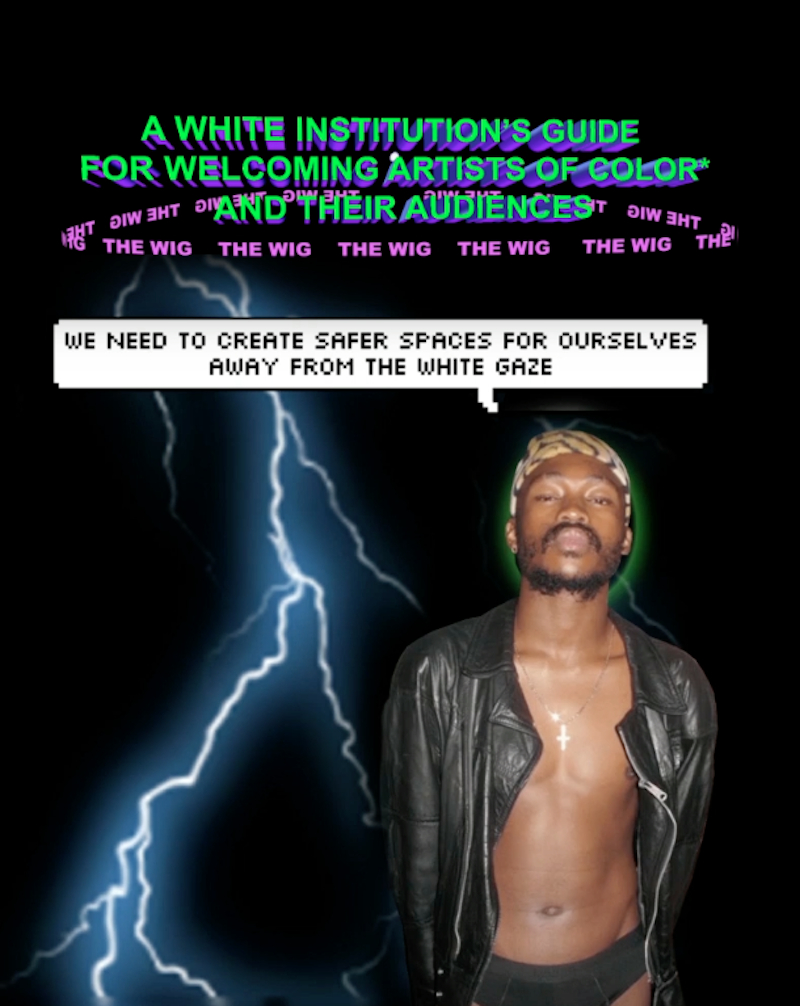

The feeling that that generates in you, in your body, is akin to stress and has been proven to shorten your lifespan. The WIG is about addressing our nervous system and soothing it. It’s about having an embodied understanding of these structural issues and how they affect our physicality, our presence and our lives. And how that is accumulative. Every little interaction matters on a nervous system level. The WIG asks: How can we move toward soothing our nervous systems? Do I think that workshops in structural race training will create the revolution? No, I don’t. But I still think it’s worth it and really important for us to vocalize what we need.

I’ve been looking at all the GoFundMe’s that have been circulating recently and I see some that are for $1000 or $1700. It’s a lot of money for the people, but I’ve seen the budgets that some institutions deal with and this is nothing in comparison. For them, it’s basically a tip. It made me think about how we have to ask for two, three, four or five times more than what we need for a project. It needs to be a shared code with the institution: Nothing you give me is ever going to be enough. So let’s embrace the conflict and look at it, face to face, and accept that it’s not enough. That conversation needs to be normalized.

Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa: ‘Black Power Naps/Siestas Negras’, installation view with Ebony Donnley // Photo by Avi Avion

AH: You spoke about soothing the nervous system in relationship to dealing with the white institution. Your project ‘Black Power Naps / Siestas Negras’ with Navild Acosta deals with the redistribution of rest, relaxation and down time as a form of radical reparation. Can you tell us about some of the installations that you made as a part of that project?

FS: The WIG is about digging into the dirt, and being angry and putting it out there in a really articulate and concrete way. ‘Black Power Naps’ is another side of the spectrum that asks: If we were to stop fighting and not defer our dreams, like Langston Hughes says, what would we do? How would it look?

The ‘Black Power Naps’ project is the same type of work as the WIG, but from another point of access. We really focussed on the senses and on finding sensory calming baths in different incarnations in order to imagine this. There are different islands and each island has a premise around resting while Black. The ‘Black Bean Bed’ is a pit filled with two tons of dried black beans. It has survival blankets and lavender hanging. There’s an ecosystem that happens: People go into the ‘Black Bean Bed’ and the beans are very astringent, they massage the limbs like acupressure. The body heat gets absorbed by the superficial layer of the beans and is refracted by the survival blankets, which then heats the lavender, which drops essential oils on the people that are in the pit. The idea is to soothe the nervous system in relation to panic attacks: You can submerge yourself fully under the beans and still breathe. There’s also a blanket weighted with black beans, so you can really create the experience of a closed environment that muffles sound a bit and calms you.

There’s also an island called the ‘Pelvic Floor’, which is a big trampoline with subwoofers and drum shakers under it, and a big canopy that we made with special lights. Throughout the installation there is a lot of highly pigmented colors. We find it really important to de-clinicalize spaces of rest. It is ideological that spaces of rest and leisure are white and “clean”. Our idea was to play with color while still being soothing. You can jump or lay in the Pelvic Floor, or you can do both. The jumping part has to do with seeing rest as something bigger than just sleeping; it’s also downtime and being able to move your body playfully—without productive ends. As Afro-diasporic people, as Black folks, we are extremely regulated in how we can do that. Black folks moving in public need to do so for productive ends. Leisurely Black movement is criminalized, and we seek to create a space that cancels this postural racism by adressing social ergonomics. The idea with the jumping is to generate this type of breathing where your diaphragm goes all the way in and out. It’s a type of breathing we seldom have as adults. As children we are much more intuitively in touch with it. As adults we lose touch with our core and with our breathing. Jumping and being received by the membrane creates a specific circulation of blood and oxygen in the body and cleanses blockages and stagnant energy.

These are simple physicalities that we are structurally deprived from. ‘Black Power Naps’ shows how these can be dynamics of reparation, and embodiments of what that looks like in public space. In Miami, when we showed ‘Black Power Naps,’ it was $12 for white people and free for Black folks and people of color. That really made a difference in the constitution of who was present there. It was a bit of a bittersweet victory because it wasn’t officially announced, but it was implemented at the entrance.

Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa: ‘Black Power Naps/Siestas Negras’, installation view // Photo by Avi Avion

AH: It goes back to your idea about the work of the accomplice: that was obviously the threshold of the law for that institution. One final question: In the WIG you have an asterisk beside the formulation “artists of color” and a bit of a breakdown of what you mean by that term (pro-Black, pro-hoe, femme-centric, anti academic, non-European, decolonial). Can you explain?

FS: “People of Color” is often used to erase or censor unambiguous Black people from spaces. Language fails us, and we know that. It’s important for me to acknowledge that this is a placeholder. It doesn’t stop at artists of color; it is much more than that. It is not a theoretical treatise about what a white institution or an artist of color is. It’s about making sure that sex workers are acknowledged for their contributions, trans folks are able to be welcomed and their presence paid and accounted for, migrant people, gender nonconforming people—there’s an endless list of folks who are marginalized from these spaces. I just want to not let it be one dimensional.

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Institutional Critique.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

fanniesosa.com

patreon.com/fanniesosa

Fannie Sosa: ‘A White Institution’s Guide for Welcoming Artists of Color* and their Audiences’, 2016, text by Fannie Sosa, visual elements by Tabita Rezaire in collaboration with Fannie Sosa // Courtesy of the artist