Interview and portraits by Sofia Bergmann // Oct. 8, 2020

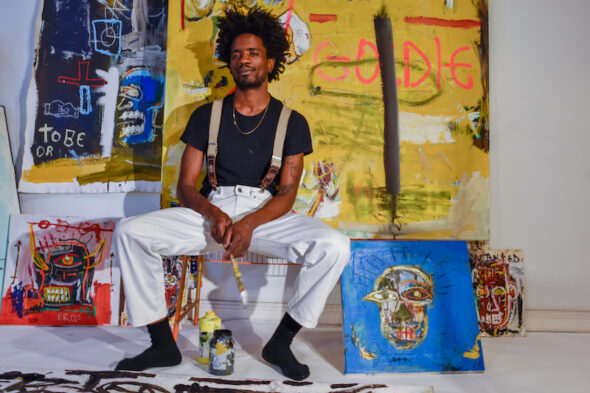

He and his work could be mistaken for Jean-Michel Basquiat but Álvaro Guilherme is no impersonator. Rather, he is creating the Art Brut of today, and he calls it New Brutalism. In Guilherme’s conception, New Brutalism as an artistic movement lives outside of any pre-existing labels because it manifests the lifestyle of contemporary emerging outsider artists, artists like him. It’s a lifestyle that is sometimes uncertain and spontaneous, but integral to the art that results from it.

Guilherme is often between studios, selling his art on the street, working with found materials, collaborating with curious strangers and storing his rolled up canvases with friends and in basements where he can find space. The artist—sometimes known as Al Varo or simply Al—has a modest Instagram following and he never walks around with a stack of business cards. Yet, he has been invited to exhibit his paintings and is offered generous sums that keep him afloat. Recently, he participated in the Black Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art and Discourse, and his paintings were shown alongside those of two other ‘New Brutalists’ in Kunsthaus KuLe, a nonprofit art space previously squatted by art students of former West Berlin, after the fall of the Wall.

Álvaro Guilherme // Photo by Sofia Bergmann

Located on Auguststraße in Mitte, it is surrounded by Berlin’s most prestigious art galleries, museums and institutions. This interesting contrast is what Guilherme considers to be a form of rebellion. “I’ve been making art to survive…this exhibition was kind of a revolution of making art, like a manifesto. The act of making it is really important to keep you alive, to push you, but it’s a dangerous place,” he says, because with it comes great uncertainty in an often elitist industry. We spoke with Guilherme about his work and the lifestyle that is so connected to it.

Sofia Bergmann: You recently exhibited your ‘New Brutalist’ paintings as part of the Black Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art and Discourse, which took on issues like decolonialism, the Black Lives Matter movement and racial equity in the arts industry. Do you consider your work to be a form of activism?

Álvaro Guilherme: It’s curious because, though my work could be put in that category, it is more about the act of creating, for me. I’m not trying to put myself out there as an activist. If I do then I must also give opinions and prove something. I am trying to be present, and the result can create a form of activism. In some ways, I’ve been an underground activist because of the action of creating the art itself, but I am more the messenger. The works themselves can be really dramatic and can influence people in an activist way.

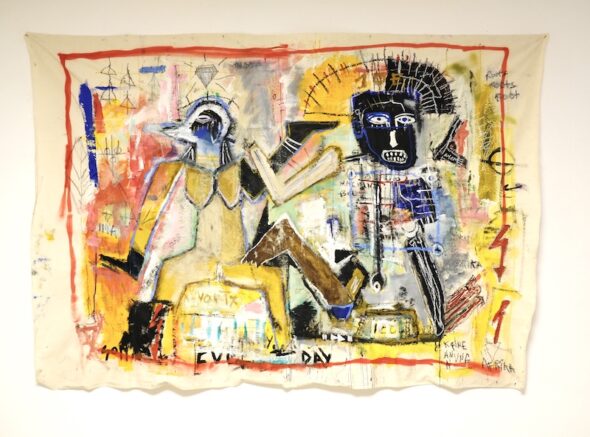

Álvaro Guilherme: ‘Ophelia Dance to Joe,’ 2019, Acrylic, mixed media // Courtesy of the artist

SB: As you are from Angola, a former Portuguese colony, what did contributing to this Biennale mean to you?

AG: It was a good opportunity to get closer to the culture and roots. It was more of a way to show that it’s not just about the Black Berlin Biennale, but that there are real cultures affected [by colonialism]. The point was not to discuss African colonialism with my art or to take a political side, but that the way of working and the expression of each artist [presenting alongside me] brought this nostalgia to the things we live and experience today that are still associated with colonialism. Rafaella Braga is Brazilian, Thomias Radin is French-Guadeloupean and I am Angolan.

SB: Your painting method appears to be quite spontaneous and almost experimental. I’m curious about how much time you spend planning your paintings?

AG: Before I even started painting, I basically just used notebooks, which gave me the possibility to be in the rhythm of planning and reacting to my surroundings. So there are works where I am planning and gathering the materials that I am able to use when it’s really needed. But, if I plan too much, it wouldn’t be the same. Sometimes, at the end of the day, the painting will say: “Yo, don’t touch me anymore!”

Alvaro Guilherme: ‘AK 47,’ 2019, Acrylic on canvas // Courtesy of the artist

Álvaro Guilherme, portrait // Photo by Sofia Bergmann

SB: You often paint with your hands and it seems you have a very physical relationship to your medium. Can you tell me more about your method and how it developed?

AG: It is developed by the rhythm of the music I am listening to. Sometimes the reaction between the music and the color is the hand—if not, it comes from the brush. So music has helped me a lot in the process, and the hand is the flow.

I use the hand more now that I am open with my work. I am more secure with my hands. For example, sometimes I’m painting with a brush and maybe I want yellow but black also makes sense, so blending with the hand makes me more connected with the work and gets me closer to the movement and sensation. It’s all about the movement of a feeling.

Álvaro Guilherme: ‘Welcome to the Hell,’ 2020, Oil stick and mixed media // Courtesy of the artist

Álvaro Guilherme, portrait // Photo by Sofia Bergmann

SB: The recent video you produced with Liao Kai Jou and Dario Zöller, in which you wander around Berlin with a trumpet asking for a cigarette, is called ‘Welcome to my Hell’. Your paintings are also very evocative and ruthless. What experiences are you revealing in your work?

AG: My paintings are sometimes the product of questions I am seeking, and other times they are really the answer. ‘Welcome to my Hell’ was a response to corona, this lifestyle, being a Black artist trying to survive in Berlin and trying to make it happen. The video was about what happened throughout this process and the cigarette that led me to meet a lot of people.

We were in the studio for ten hours, so this journey was like hell. But it’s more of a play on the word, a metaphor, because at the end of the day we are still alive. We can still make something, we can still paint. I could have said welcome to my heaven, but my painting is like a slap! [claps his hands] It’s not trying to comfort you: it’s screaming, it’s noisy.

SB: Would you say that New Brutalism is your ‘hell’ and you’re saying ‘welcome’?

AG: Yeah. And probably if I had a studio and was settled with all my materials, I would not produce the same work because it’s a different challenge. Now, it’s a challenge of risking: I’m exposing myself, this is my work.