by William Kherbek // Apr. 16, 2021

Artist and researcher Karin Bolender’s recent book, ‘The Unnaming of Aliass,’ tells the story of the writer’s enduring relationship with a donkey or, rather, an American Spotted Ass, a selectively bred creature complete with a website and self-appointed council dedicated to its visibility and promotion. Bolender’s narrative is a kind of comic phantasmagoria rooted in the tradition of the American Southern Gothic, richly infused by the region’s literary lineage. At the heart of the tale is a marriage ceremony Bolender undertakes with Aliass—the name she assigns, or “unnames,” as she puts it, her equine partner—to cement their commitment. The two then proceed on a long, somewhat perilous, journey through the American South. The peril is as much metaphysical as physical, as Bolender considers the relentless, extractive violence that has created the America through which she and Aliass traverse.

The pilgrimage is a familiar literary ritual, and marriage is often the culminatory rite of classical comedies, but Bolender’s book seeks to take these familiar framing devices and push them to and through their limits in order to find what lies outside the frames we create to understand the world and what we tell ourselves about it. ‘The Unnaming of Aliass’ is a chronicle of ambivalences, including Bolender’s own in writing the story out, but also one of longing. There is a tangible longing for personal insight, and Bolender wants to subjectively interrogate the poet Gary Snyder’s observation about the prevalence of interspecies marriages in myths from distinct cultures, how they express, in his words, “the possibility of full membership in a bioerotic universe.” Bolender’s narrative, mercifully perhaps, is less focussed on the overtly erotic, and more on the kind of ritualistic generosity expressed in the work of artists like Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle. While the book offers a somewhat circuitous narrative, and readers with an aversion to the punnic possibilities of the word ‘ass’ should approach with utmost caution, the heartfelt gesture the book expresses provides a perspective on the ways in which ritual and endurance shape human experience, and how they can play a role in expanding it.

Karin Bolender: ‘Prettiest Little Shotgun Wedding You Never Saw,’ Paris, Tennessee, June 2002 // Photo by Sebastian Black

William Kherbek: The role of marriage as a “rite of passage” and as a way of consecrating and constructing identities is a subject you touch on in the book. Can you describe how you decided marriage was the specific ritual—given the historical, political, and gender-based dimensions that have characterised its evolution—that you wanted to use to affirm your connection to Aliass?

Karin Bolender: I think it’s really important to say that we’re talking about a 20-year span of time. These are things I’ve been thinking about for 20 years, reinforcing in some ways, rejecting in others. They were different than they are now. There’s definitely been an evolution of thought, but the question of marriage taps into something that’s the heart of this project. The first ritual that happened, right at the cusp of the journey that Aliass and I set out upon, that first wedding in Paris, Tennessee, was kind of a mixed and wild, improvised thing that we just put together really quickly. If I had to name that ceremony, it was a secular, paganised, very-culturally-specific-to-Paris-Tennessee kind of blessing, like, “here’s a blessing for the mission ahead of us.”

It was only when we were in it for a duration, when we were doing it, that I realised that this was something that had a level of depth of commitment, something we’re going to survive. I certainly wasn’t sure going into it that we would. Once it was happening, that was when I started to think about the wedding. At that point, it made sense to say this is a life; not so much that I’m marrying Aliass, or she’s marrying me, or I’m claiming her, but that we’re both permanently enmeshed in this relation with this project going forward.

People often ask me: what happened to Aliass after the journey? Do you still have her? And I’m horrified. Like, of course! What am I going to do? Sell her or abandon her? We are really genuinely, durationally in this together, whatever it turns out to be. And the renewal of the vows are really the centre of the writing. That, for me, is the truest writing in the book. I have a lot of ambivalence about the book. It was a book that was not supposed to be written. It’s a book about what can’t be told. But, if there’s a core, a heart of it, it’s in those vows. They were pre-performed in the first ceremony in Paris, Tennessee. They were kind of intuited, willed into being. Then, a year later, in the spring, I actually performed them. I did this performance with some collaborators and Aliass, and, technically, “remarried” Aliass with these specific vows. Most importantly, I feel like the vows are a score for an ongoing living art practice that is the Unnaming of Aliass, that is until death do us part.

The shadow of a lovely spotted ass, yet to be unnamed, in Whites Creek, Tennessee in April 2002 // Photo by Karin Bolender

WK: In addition to the marriage, the ritual of the pilgrimage makes up a significant portion of the narrative of ‘The Unnaming of Aliass.’ You use Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy as literary touchstones, but the pilgrimage is central to the history of literature, from The Canterbury Tales to The Satanic Verses and beyond. How did you envision the status of pilgrimage in your project and what did that (pseudo-)pilgrimage illuminate for you?

KB: Much of my early training and early practice was in literary studies and writing fiction, and I think that I definitely had a sense that I wanted to shake off all of these inheritances of certain narrative tropes. And, of course, that’s impossible to do, but I wasn’t as conscious of it then. I think I was intuitively conscious of it, but not as overtly aware of it as I am now.

I came to realise the pilgrimage, now as I think of it, was a frame to turn inside out, so that it does function as frame. I’m subverting it, but I still have the frame of the journey. I would say that I wanted to turn those traditional narratives inside out to make room for the untellable, the wildly dynamic ecological flows of experience beyond human language; the pilgrimage was very important as a frame, even if I’m in a critical relationship to it now.

Aliass on the road outside Oxford, Mississippi, June 2002 // Photo by Karin Bolender

WK: To speak more about your practice in general terms, performance and performativity often have a strong ritualistic dimension. They can work as enactments, sanctifications, or forms of catharsis, for example. Is ritual something you see as a central part of your artistic practice?

KB: I had a really vague idea of what performance art was when I went into this. I had studied Dada, but I was a literature major. When I started the journey in 2002, I had never heard of Joseph Beuys. I knew a bit, peripherally, about [John] Cage, and more about Duchamp, but not the implications of Duchamp for performance. But, years later, I found my moorings, and I found my modes of articulation historically, and moving into contemporary thinking. I’d also mention Linda Montano in that sense of durational living art practice. I was really startled when I found her work, because it felt like, “yes, this is what I’ve been trying to do and think.”

I also teach and I always find it really wonderful to teach performance, because people come into it thinking we mean [something like] a dance for an audience. I think that, having that idea, I would have thought “performance” is not what I’m doing. I’m not performing for an audience. But then I did think of it as engagement with a broader audience, which doesn’t happen to be human, not even an audience per se, but a matrix of collaborators. I couldn’t have articulated that without having studied performance.

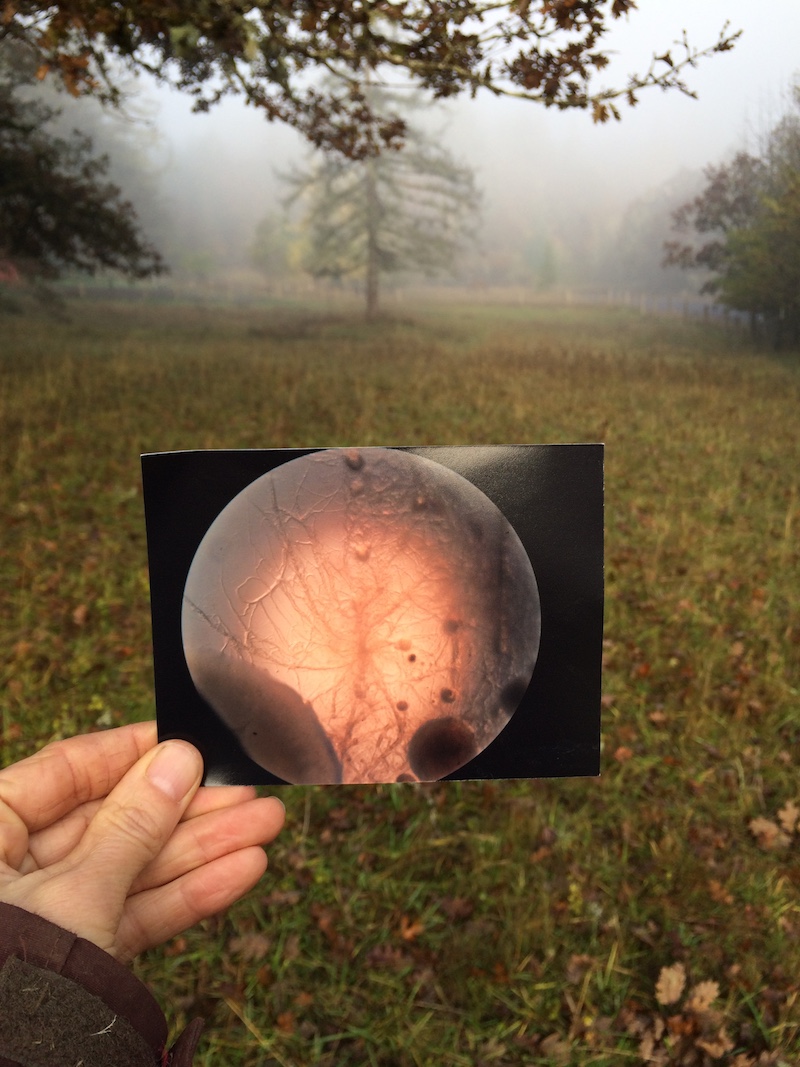

Original ‘Welcome to the Secretome’ treasure map made from culturing Aliass’s muzzle tongue // Photo by Karin Bolender

WK: Presence and subjective experience could be thought of as central both to performance art in general and your own work, not least the book. How has the last year affected your understanding of the role of and need for performance in culture, either within a ritualistic context, or as a kind of rupture with quotidian experience? Do you feel that the pandemic will have long-term impacts on performance art going forward in your work?

KB: A lot of my work has been about intimacy and place and so, certainly, in our stay-at-home mode we have had the opportunity to deal with questions of intimacy and home and place. I have a project that’s been going on for a number of years called ‘Welcome to the Secretome,’ and it involves using microbial cultures as treasure maps in specific sites. You culture something; you grow the microbial culture; you make an image; and then you take that and pretend that it’s a map. I had started doing that work, right here in our little donkey pasture, and I had invited others to do it over the past year with my family, particularly with my daughter, because she’s home, and we’re home, doing this work together. We had a few opportunities to engage the project with collaborators, and it was completely transformative. It genuinely was. There were things that came out of that experience that I think I’ll be processing [for a long time]. I’m very committed to the indeterminate, and to process against product, but the power of framing time and framing a configuration—what happens if you take this amount of time and put these elements in it—that’s what interests me.

R.A.W. PostLibrary, a durational stay-at-home residency, first opening as part of AntiAesthetic/Eugene Contemporary Art’s Common Ground program in 2020 // Photo by Karin Bolender

WK: In that you mention this notion of process against product, one of the key moments in the book is the production in workshops of soap using ass milk. In some ways, the creation of a product and its inherence with value is the oldest ritual in the art world. I wonder if you now would approach the creation of the soap as object differently?

KB: Oh my gosh yes, I’m so opposed to the object these days that I can’t even tell a story any more. I’m hesitating at the edge of narrative.

I’m still negotiating the presence of this book, because I’m not sure about this book. One of the things I made in the past year was the ‘Post-Library.’ The idea of the R.A.W. ‘Post-Library’ is that it asks the question of what comes after the book. And what I mean by that is trifold, or more. What comes after the culture of the book, the Judeo-Christian tradition of all information being contained in the book, and the book being the authority, and human language, and all that? The next question is material: the material object of the book. What is this object of the book? How do we become responsible to its histories and its dimensions? Lastly, there is my book, which I don’t feel is mine, and I wasn’t sure should be written, and I’m still not sure should exist. I need the book to consistently question itself, and whether it should exist.

The ass milk soap is a powerful concrescence, but it also feels like a little bit of going astray. It’s a kind of landmark that I’ve passed by, it’s important, but I’m definitely moving in new directions from it, as an object. That still leaves the question of how you function in the art world, or in the broader economy, if you don’t make objects. I’m asking that question. I’m living it.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Ritual.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Additional Info

R.A.W. Assmilk Soap hand-washing installation at the Multispecies Salon Ironworks exhibition in New Orleans, Louisiana in 2010 // Photo by Sean Hart