by Lucia Longhi // Apr. 27, 2021

Artist Jan Swidzinski, among the theorists of contextual art, wrote in his 1988 ‘Freedom and Limitation – The Anatomy of Post-Modernism’: “Being an artist today is talking to others and listening to others at the same time – not creating alone, but collectively.” Participation is at the core of Marinella Senatore’s work, wherein she creates group performances through a negotiation of forms and meanings with communities. Therefore, her artistic practice could be referred to as contextual art: collective events in urban spaces, or in the landscape, including activist practices with and for the community. In light of this, the artist’s performances are also configured as rituals capable of tracing new lines of meaning.

Born and raised in Southern Italy, the artist holds religious processions in her DNA: not by chance, she mutates processes and structures from the forms of religious and civil rituals. Her creative process is deeply relational too, and places communities at the center of the work, addressing concepts such as emancipation and social empowerment and aiming to activate social strengthening where the individual perceives themselves as an active part of the—local and global—community. Senatore’s relational practice involves different artistic forms, such as dance, music, sculpture, which aim to address and fight social distances rooted in contemporary society. The ‘School of Narrative Dance’ (SOND) is a long-term project configured as a series of workshops aimed at a collective performance, in which the goal is to create a narrative through the body. The performers come from local contexts and the artist involves entire communities, without limits of gender, age, sexual or ethnic affiliation. The SOND can also have an educational function, as Senatore explains in this interview, where she also tells us about her future projects like the Biennale di San Paolo.

Marinella Senatore: ‘Little Chaos #1A,’ 2013 // Courtesy Mazzoleni London, Torino

Lucia Longhi: Starting with a reference to ethnological tradition, rituals can serve manifold purposes: accompanying an individual or the community from one state to another, separating, aggregating, tracing new topographies or iterating old and eternal ones. Your work draws so much on rituals and, in several cases, on religious ones: with reference to the above, where would you place the meaning of your performances?

Marinella Senatore: Popular culture, processions, community music and dance, and also all my experiences as an activist, are all forces that converge and reactivate, or activate new experiences for the first time: the energetic potential of tradition, history, memory (in general, heritage) is not static for me, but aimed at the reactivation of something else. The same happens with the large luminous structures that I create: they derive from tradition, usually linked to usually festive or religious rituals, of the typical lights of South Italian tradition. They also evoke a social meaning and my ancestral love for light, in its multiple narratives. For example, when I recreate rose windows and baroque portals, these become like mantras: catalytic elements of energy standing like monuments to the present, to the people, to the here-and-now. This is crucial for me.

Marinella Senatore: ‘We Rise by Lifting Others,’ 2020 at Palazzo Strozzi // Courtesy of Mazzoleni London, Torino

LL: Your performances can be read as great collective rituals where people perform gestures and move through spaces. Normally, in rituals, both religious and civil, the actions of the participants are predetermined by dogmas, protocols, codes. In your performances, the moving forms of body language are established in a collaborative way. What are the actions that characterize your performance? Through what processes are they built?

MS: I studied classical music, cinema and contemporary art, therefore I am a multidisciplinary artist by vocation. Languages, for me, represent possibilities of involvement and experience: a new energy can originate from the short circuit of them in our actions on the street. These are new encounters: some languages, such as parkour, kramp, slam poetry to name the latest ones, can be used or even discovered during the projects. Working with people and teaching in a truly horizontal form opens up new possibilities for me. The approach to movement is always different and it could not be otherwise: we work on the bodily vocabulary of individuals and in relation to groups, no imposition from above, only the discovery and flowering of narratives that are already in the body, or that could potentially explode in the collective encounter.

Marinella Senatore: ‘Shenzhen #2,’ 2018 // Courtesy Mazzoleni London, Torino

LL: Authorship is an aspect that undergoes a radical transformation in your work: it turns into collective authorship. What is your role in your work, especially in performances? How do you structure the community’s participation? And how does your work change when the initial idea goes through negotiation with the involved community?

MS: Michelangelo Pistoletto wrote: “To participate means to surrender a part of me to those who are willing to surrender a part of themselves.” In my view, the production of meaning in participatory art is not exempt from sacrifices, which are absolutely not a problem for me! I am an activator and I regulate and adapt my presence a lot, sometimes it is necessary to take a step back, let situations, ideas and flows of thought be generated without oppressing or becoming a control figure. I am a guarantor of the dignity of each individual participant and this is a very serious thing, but I don’t want to be abusive, otherwise the result would be an idea of mine out into action, and a series of people responding to my orders disguised as tasks. I have no respect for this type of methodology and I think it is far from participatory art, certainly very far from what I am interested in doing.

LL: Your practice is also strongly characterized by a social commitment: a bottom-up activism that succeeds in subverting, at least momentarily, some social patterns that attribute limited roles and labels to people. You have involved schools, elderly people, asylum seekers, people with disabilities. Can you explain what is the purpose of engaging these different groups, and could you illustrate how social empowerment is deployed in your work?

MS: Participation, both as a structural methodology and as a theoretical focus, is integral to my entire practice, so it wouldn’t make sense not to involve anyone who wants to take part in a project, just as I think it is absurd not to support feminism or fight white supremacy. It would turn out a contradiction, an act of exclusion, and on the basis of what? Different potentials, bodies, social status, vulnerability? These criteria are often subverted in my projects. For example, in the ‘Palermo Procession,’ part of the Biennale Manifesta in 2018, the energy was so explosive that people from the audience broke into the performance, and this diluted the structure of the performance itself (it lasted five hours instead of two!). On that occasion, I also recall the incredible emancipation and dignity of a group of blind people who were in the front row leading the entire procession. I’m not interested in some kind of self-referential art addressed to an elite: I even find it dangerous.

Marinella Senatore: ‘Palermo Procession #1,’ 2018, fine art print on epson hot press paper, 80 x 105cm // Courtesy of Mazzoleni London, Torino

LL: Your performances often take place in institutional or public spaces, such as streets and squares, and they are not static. A lot of movement is involved. In some religious rituals, walking through a pre-established space serves to draw lines of meaning and reconnect the social fabric of the community. How do you choose the places for your performances and how do you define the routes? What is the meaning, for you, of walking through those places in the form of a collective procession?

MS: Since the beginning, the road was the natural place for the final outcome of these processes, because the road should belong to everyone, but it also carries a further and fundamental value: the possibility of totally redefining oneself. Think, for example, of those who go through it carrying the frustrations of everyday life, or those who live in it to beg. The artistic process completely deconstructs social roles: you can bloom, you can feel so important and decisive for others. This must be an incredible experience for those who live it, as well as for those who have the chance to see it.

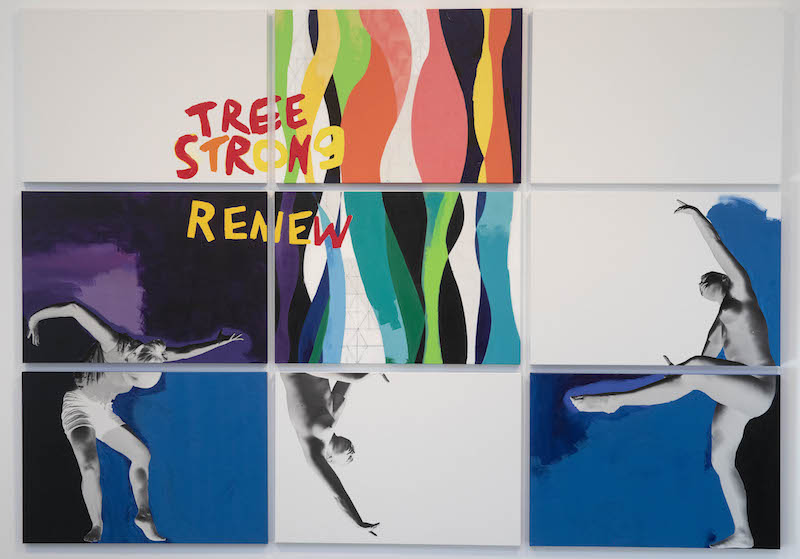

Marinella Senatore: ‘Un Corpo Unico,’ 2020, 9 pieces // Courtesy of Mazzoleni London, Torino

LL: With the advent of the pandemic and all the restrictions, we have changed our habits: we had to give up some collective events, but we have also been able to rethink some of them, creating new personal and communal rituals. Much of your practice is based on not only mental, but also physical closeness between people: how did you manage to redesign your performances and how has your work changed with the pandemic?

MS: I founded the School of Narrative Dance in 2012, following the “Project Rosas,” in which over 20,000 people had participated in one year of work. After that experience, a very urgent issue emerged: it was clear to me that we needed a “vessel,” a sort of umbrella under which I could define this type of belonging, a common denominator for the many experiences around the world. The School of Narrative Dance has always also worked using online platforms, as what I am interested in is primarily participation. Social groups, like the elderly in nursing homes or prisoners, kind of set out the process this time: in the first lockdown, we were working in Amsterdam (the film will be presented in a few weeks) and the success of the project “We rise by lifting others,” commissioned by Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, also testifies to its usefulness. And I want art to be useful.

LL: Can you tell us something about your upcoming projects?

MS: I am working on a new project for the Biennale di San Paolo, where the pandemic situation is very serious and the School of Narrative Dance can also have an educational purpose. I am also working on new projects for the Momentum Biennale and the Berlinische Galerie, as well as for Der Steirische Herbst ’21 in Graz. I am also working on many public artworks and personal exhibitions in museums and foundations in Italy, and my first solo show at Mazzoleni Gallery in Turin is scheduled for October. For me, it is very important to extend this type of practice to the art market. Finally, I just joined the teaching staff of The Alternative Art School, founded by Nato Thompson. At the moment, I am the only Italian, indeed the only European. I take this assignment very seriously: teaching is a political responsibility, so I am very focused on the communities we are creating there: a sort of Black Mountain School of our century.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Ritual.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

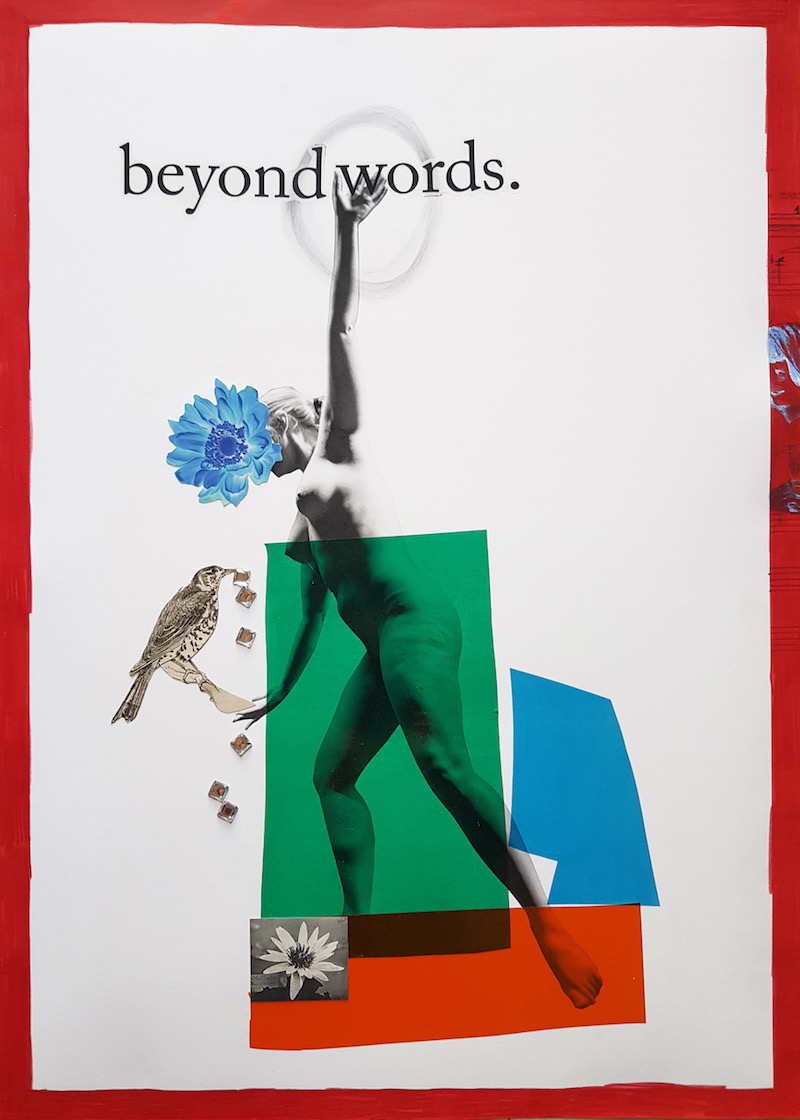

Marinella Senatore: ‘Can one lead a good life in a bad life?,’ 2020 // Courtesy of Mazzoleni London, Torino