by Juan José Santos // Feb. 18, 2022

eeefff is the collective name of Nicolay Spesivtsev and Dzina Zhuk (also known by the alter-ego Bitchcoin), who are based in Minsk and Moscow and have been active since 2013. They are often seen in art exhibitions or lecturing at art colleges, but they do not strictly define themselves as artists. In fact, reading their statement, they might be best understood as a cybernetic political brigade, with the soul of a poet. They create digital works, modify code, erode interfaces and hack other people’s websites; but they also affect the “real world” by calling for public actions, performative seminars and even open air picnics.

Although eeefff acts primarily in the virtual sphere, they are against the celebratory use of technology and digital art that perpetuates the predicates of extractivist capitalism. And, despite working in two countries that are not often friendly towards activists, their political commitment is indelible. Recently, they enacted ‘All you need now is in pinned messages,’ a cybernetic action that aims to get internet users out of their comfort zone, confusing algorithms; and ‘Economic Orangery,’ where they proposed a game for cultural and social workers that was linked to the Belarussian Revolution. With ‘Outsourcing Paradise,’ they developed a code that was introduced into the websites of various institutions, such as the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. We talked to them about their work, their philosophy around “digital materiality” and their goals as a collective.

eeefff: Screenshot of the eroded interface, 2020 // Courtesy of eeefff

Juan José Santos: Your work is sometimes totally digital, and sometimes it has one foot in reality and another in the digital. Do you differentiate between them when you think about your next action?

eeefff: For us, it’s more interesting to think about relations that can form the duality of “reality” and “digital.” We think about the production of these kinds of divisions, and who is involved in the process. In the end, behind these divisions there are relations between people with conflicts and contradictions. And things someone might call “purely digital” have their materiality anyway—with data centers where all the data is stored, people supporting the infrastructure, invisible labor of outsourcers, patent and copyright laws. This “digital materiality” is often the focus of our interest. But we by no means work with romantic practices around the “digital sublime” (be it cyberpunk or techno-singular dances around the artificial intelligence hype).

eeefff: Guided tour through Economic Orangery, 2021 // Courtesy of eeefff

JJS: In ‘Outsourcing Paradise’ you enter other institutions’ websites, such as the Garage museum, and you intervene. What was the mission of that work?

eeefff: We are interested in creating a situation where the focus is on the invisible work on the other side of the screens. It might also be nice to disassemble the narratives that support the culture of “digital” consumption, which marginalizes the worker and corrupts the labor ethic by replacing it with a consumption ethic. Glossy interfaces of modern web designs with their aim to curate the affect of the user are a great starting point for these practices. Here, our method is the deconstruction of user experience, the manifestation of its non-neutrality, construction, political and economic conditionality.

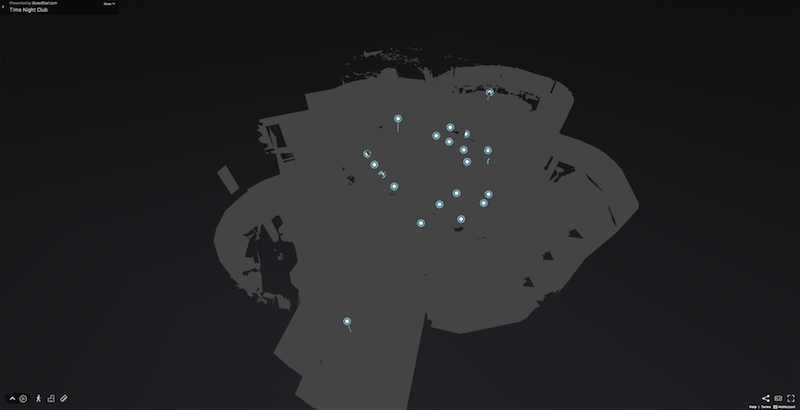

On the whole, the figure of the “user” naturalized by means of technical progress needs to be shattered and stricken, for its own benefit. For us, it’s interesting to build a stage where users turn into human bodies being oppressed and oppressing others, at the same time. ‘Outsourcing Paradise’ is an impossible club of workers who are spread across the globe and who structurally cannot unite. So, being inactive in front of your screen, pausing your online activity, you can give rise to a club of outsourcing workers—a place of distributed oppressions, pleasures and reflections.

eeefff: 3D-model of Time Night Club with textures blocked / screenshot of matterport interface hacked by eeefff, 2021 // Courtesy of eeefff

JJS: In your recent text ‘All you need now is in pinned messages’—presented as part of Berlin-based series Montag Modus’ curatorial project ‘Ecology of Attention’—you want to go against the logic of the content suggested to internet users, developed by algorithms. You want to get the user out of their comfort zone. Why do you think this is necessary?

eeefff: In this text, we are interested in keeping the intertwining of two perspectives. One perspective looks at the tools of organizing human attention as a means of modern production: our neural activity is not personal anymore but is used to produce value. Our interest here is human bodies with their fatigue, stress and depression.

The second perspective looks at the emancipation of our attention mechanisms, the cyborgized attention. We can start thinking about it in a situation of a very bodily experience. The everyday experience. What tools are involved in the construction of our attention? What would an attention strike mean? Here, the idea of the user acquires an active connotation. The user becomes an agent by influencing the interfaces and devices for his or her own needs. We are interested in how this drama of becoming-agent is unraveling. For that to happen, it might be useful to get out of our comfort zone.

We unfold our ideas from the situation in revolutionary Belarus in 2020–21, where we see the potential of reassembling the tools for distributed revolutionary action: chat rhizomes, repositories with source codes of programs, tools for collecting resources, algorithms for checking the reliability of information, maps highlighting the localization of violence. In this situation, simultaneity is supported by a specific set of tools for acting together, but at a distance. We wonder what temporalities can be born out of such a distributed, ongoing rebellion?

eeefff: Guided tour through Economic Orangery, 2021 // Courtesy of eeefff

JJS: In ‘Economic Orangery’ you propose a game for cultural and social workers, rooted in the Belarusian locality or experienced by living in Belarus. For what purpose?

eeefff: ‘Economic Orangery’ is a playful two-month long collective situation with the focus on alternative instituting. Events inside of the orangery went in parallel with the actual Belarussian revolution, where since August 2020 multilayered protests have been taking place due to the falsification of presidential election results. We think this overlapping of two temporalities—a fictional one and the temporality of the uprising—was the key experiment for all participants. A distant view from the speculative setting where all the technologies of today are fossils intertwined with the necessity of immediate action. The space between these two perspectives was the space of collective speculation.

JJS: Is there digital censorship in Russia and Belarus?

eeefff: Censorship in the internet is part of broader practices of both governments, aimed to oppress social groups that confront regimes of governability in Russia and Belarus now. For solidarity networks, the stake on transparency cannot work, for safety reasons. In Belarus, there are laws against “extremism” that affect NGOs and individuals, acting both offline and online. In Russia, there is a law against so-called “foreign agents” that concerns those who receive foreign funding. Both laws attack resource flows of cultural initiatives. In our opinion, there is an overlapping oppressive opacity—say, censorship—and an emancipatory one. So now it’s necessary to establish safe zones where other “topologies” of institutions can be tested.

Picnic Near Data Center, 2016 / Photo by eeefff

JJS: Another of your past actions that really got my attention was ‘Picnic Near Data Center,’ in which you invited people to meet near a data processing center. What was the intention behind this work?

eeefff: We organized the picnic in 2016, when the Moscow municipality began a large-scale process of gentrification in the city. We were interested in holding together the questions of data, bodies and streets. The idea was to collectively feel and embody the disproportionality of the digital infrastructure. A parking lot near one of the largest data centers in the city seemed to us a great place to do so. Why collectively? Because the effects of algorithms are most often experienced individually. So, a picnic in such a “non-human non-place” seemed to us a good form of clashing, of a very bodily experience and algorithmic abstractions.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Digital.’ To read more from this topic, click here.