by William Kherbek // Mar. 18, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘Occupation.’

In the Eastern Orthodox religious tradition, the concept of the “Holy Fool” has a long lineage. Readers of Leo Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’—a grimly apropos title for the 2022 reading list—will remember the character of Platon Karataev as a version of this familiar type. Karataev rejects the sophisticated reasoning of figures like the self-consciously modern Prince Andrei for a simple, clear-eyed reading of the world; one that is appealing in its embrace of humanity and the living world without regard for hierarchies or the appurtenances of power. Karataev is engaged with and connected to the world, though he is not “of” the world. Analogues of the Holy Fool in Western Christianity, English anchorites, or the Syrian Saint Simeon Stylites for example, were most often ascetics, retreating from the world of power to exemplify models of holiness or Christ-like virtue.

CATPC and Renzo Martens: ‘The Plantation and The Museum,’ 2021, 6-channel video, video still // Courtesy the artists and KOW Berlin

Today’s Holy Fools must take on the more public, Karataev-style approach, not retreating from but entering into, even confronting the world of power. Dutch artist Renzo Martens—famous for numerous, complex, sometimes repulsive, acts of artistic holy foolery—is back with a new chapter in his ongoing project at KOW in Mitte, with a group of artists based in today’s Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), The Congolese Plantation Workers’ Art League (CATPC). The work explores the depredations of palm oil barons in the region in the early 20th century and the attempt by two members of the CATPC to recover a trafficked sculpture of a savage Belgian colonial officer, Maximilien Balot, for a museum the CATPC artists have built in their home region of Lusanga, the site of a historical plantation.

CATPC against the White Cube background

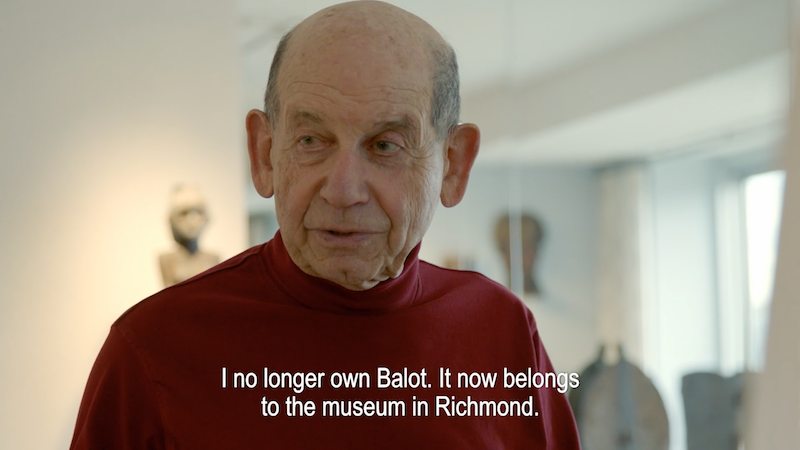

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a six-channel video work featuring the CATPC artists Mathieu Kasiama and Cedart Tamasala, who are engaged in a mission to track down the statue and to repatriate it. The journey takes them from Lusanga to the ivy covered citadels of Columbia, Brown and Princeton universities, to the home of the collector Herbert Weiss, who purchased the statue from a local Lusanga trader, to the museum in Richmond, Virginia to which Weiss sold the statue. The journey that Martens documents is by turns devastating, hilariously absurd, deeply moving and eye-rollingly sardonic.

CATPC and Renzo Martens: ‘The Plantation and The Museum,’ 2021, 6-channel video, video still // Courtesy the artists and KOW Berlin

The film begins with the artists being charged with locating and bringing the statue back to where it was created to exorcise the malign influence of Balot’s spirit in the space where he was beheaded. In this introductory video, viewers hear the harrowing tale of the takeover and occupation of the land of the Pende in DRC. Clips from a mid-20th-century documentary about the process, interspersed with contemporary footage and interviews with the professor Antoine Sikitele, leave no question of the self-conscious brutality of the corporations tasked with creating a palm plantation in “hostile” territory. Showing the apocalyptic landscape of felled trees, left behind after corporate warriors wrought their destruction, a narrator notes that the fighters in the service of William Lever and Company were ruthless in their subjugation of the land and its people. “Only by these methods,” the narrator states, were the plantations established. “Only” is perhaps the most operative word.

CATPC and Renzo Martens: ‘The Plantation and The Museum,’ 2021, 6-channel video, video still // Courtesy the artists and KOW Berlin

Kasiama and Tamasala’s interaction with academics in the next several films are less solemn, if no more reassuring affairs. Some goofy interplay with Professor Zoe Strother, a Columbia academic, and some rather self-centring and exculpating back and forth with Ariella Aisha Azoulay in her office at Brown prompt some of Kasiama and Tamasala’s most sophisticated reflections on their own project: will becoming “experts” on the work and its history change them? Will the museum they are creating be a site of liberation and community building, or will it end up as just another museum?

CATPC and Renzo Martens: ‘The Plantation and The Museum,’ 2021, 6-channel video, video still // Courtesy the artists and KOW Berlin

Their interview with collector Weiss will infuriate some viewers, and it clearly doesn’t please the local members of the CATPC community when the film jumps to their viewing of the work in the museum space they have created in Lusanga. But it is an insight into the colonial mind that is refreshing in its rarity, amid oceans of sanctifying rhetoric about the social utility of art that dominates cultural production today. The work, it seems, came into Weiss’ possession when a man sold it to him to send his children to school. A sensible notion, from Weiss’ perspective, looking toward the future rather than clinging to the objects of the past; “treason” in the words of Kasiama and Tamasala. Martens’ camera pans around Weiss’ well-appointed house, replete, as it is, with the output of African cultural production. The viewer once again sees the imperial mindset in its fullest and most honest expression. Modernity is the way, just don’t ask why education costs money in the first place.

As a work ‘The Plantation and the Museum’ has tremendous emotional range and intellectual sophistication, and Martens’ eye as a cameraperson and editor brings so many of the juxtapositions and multilayered narrative elements to the fore. Rare is it that a six-channel video justifies its technical complexity, but toggling back between stories on different screens, as one makes one’s way from the first to the last, offers a powerful “in the round” effect to the story and to the characters.

Renzo Martens: ‘White Cube,’ 2020, film, film still // Courtesy the artist and KOW Berlin

Accompanying ‘The Plantation and the Museum’ are two other video works. If you’re going to KOW, you really should block out time for your visit as ‘The Plantation and The Museum’ and the accompanying ‘White Cube’ (2020) will require two hours to watch in full. ‘White Cube’ is particularly necessary viewing for understanding the show, and perhaps is best watched before ‘The Plantation and the Museum’ as it fills in the history of the project, including Martens’ ill-fated first attempt to create an art space in an active palm plantation in DRC. The corporate “partners” send an enraged email to Martens at one point, decrying his naivety and self-regard in creating the art space as now, thanks to being allowed to think and make art, the locals have taken hostages of company workers! The facts are made clear to Martens: you can do your little art project, but only in places where total wealth extraction has already occurred. The ensuing creation of the CATPC is both revolting and inspiring. It exemplifies the kind of quantum emotional state that makes Martens’ Holy Foolery so powerful: all the institutions of empowerment are also institutions of exploitation. Sometimes art reduced to its most basic commodity form can prove the most genuinely socially-engaged and liberating art of all. It is head-spinning stuff and speaks to the crushing truths that underpin both the art world and the sacrifice zones of wealth extraction.

Renzo Martens: ‘White Cube,’ 2020, film, film still // Courtesy the artist and KOW Berlin

The other video work ‘Balot NFT’ (2022) is a single-channel video displaying the Balot sculpture at the heart of ‘The Plantation and the Museum.’ The NFT is being sold and, if the press release is to be believed, “Anchoring it on the blockchain and later disseminating it as a series of NFTs will enable [the CATPC] to reactivate the sculpture’s powers and buy back the land that was stolen and despoiled.” Martens and The CATPC are again confronting the art world with its own manias and asking what truly lies behind it. What do the exalted words about liberation and restitution mean? How many land acknowledgements do you need to say to save your soul? Whose spirit lives and works in the blockchain? Martens and the CAPTC artists may not know the answers, nor should they be expected to provide them, but in creating this work they have, at a dangerous time, placed another dangerous technology before viewers: a mirror.

As in many of Shakespeare’s plays, often it is only the fool who is allowed to see the world clearly. Martens may play a certain kind of fool, but his CATPC collaborators, particularly Kasiama, have the insight to see beneath the foolery to the truth that Martens’ works reveal. ‘The Plantation and the Museum’ is often a hard work to view, but Martens’ and the CATPC artists’ hope, beneath any cynicism or play-acting, is that art audiences will have the strength to view it and the even deeper strength to try to understand it.

Exhibition Info

KOW Berlin

CATPC, Renzo Martens: ‘Balot’

Exhibition: Feb. 11–Apr. 8, 2022

kow-berlin.com/…/balot

Lindenstraße 35, 10969 Berlin, click here for map