by William Kherbek // May 13, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ’FAKE.’

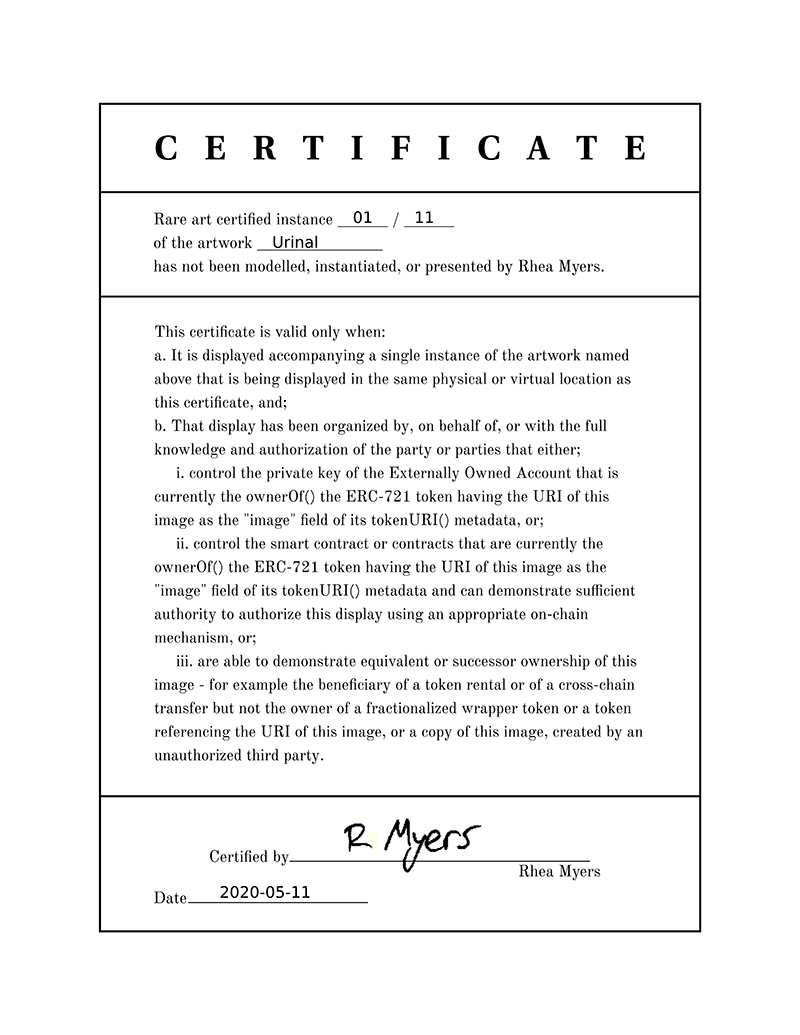

Rhea Myers has been creating art using advanced digital blockchain technologies since 2013. Her work is defined by a sophisticated understanding both of computation and programming and of the cultural place of digital creativity and tech-optimist discourse. Myers recently showed the work ‘Tokens Equal Text’ (2019) at Berlin’s Panke Gallery with other noted artists producing NFT works including Sarah Friend and Kim Asendorf. Myers’ work ‘Certificate of Inauthenticity’ (2020) builds on earlier works of hers including ‘CrytpoPuppers’ (2018) and ‘Artwork of the Century’ (2016), which take iconic works from art history, including Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ (1917) and Jeff Koons’ ‘Balloon Dog’ (1994-2000), as sources for the questioning of authenticity, creative production and valuation. ‘Certificate of Inauthenticity’ uses the digital token as a means of questioning the fetishisation of ownership that NFT culture is fostering in the art market. Myers spoke to Berlin Art Link about the work, as well as about wider notions of authenticity and its discontents within digital cultures.

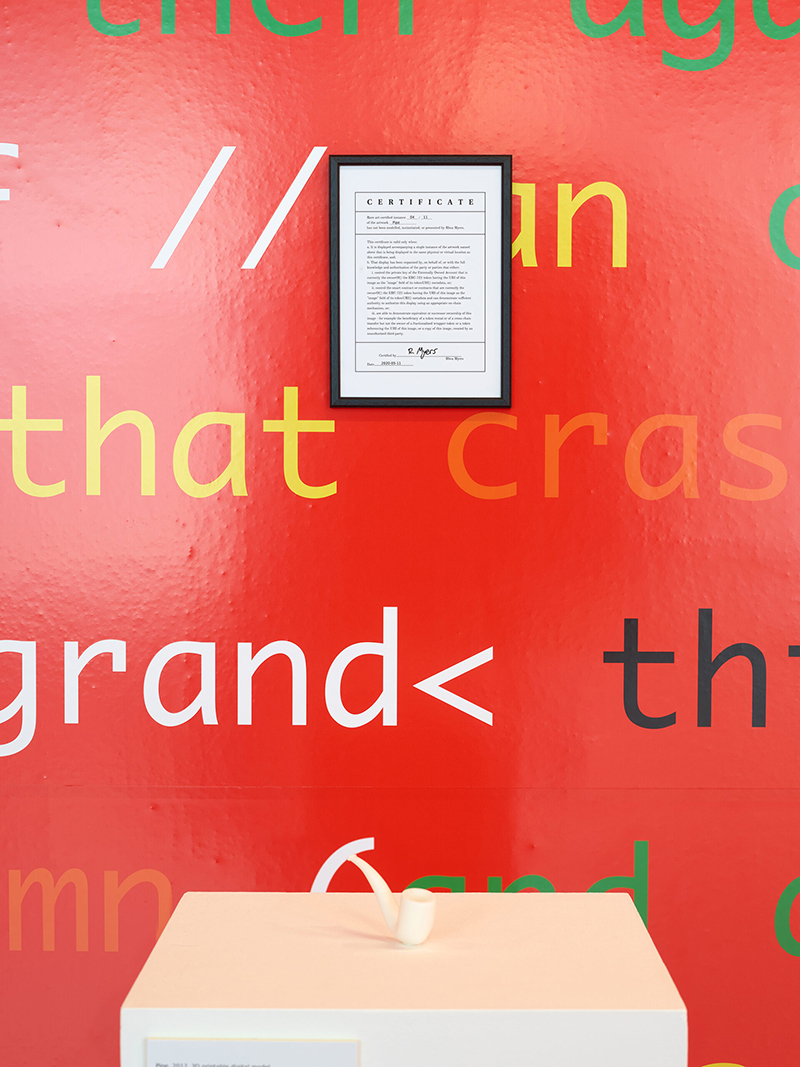

Rhea Myers, ‘Pipe,’ 2021, 3D print and framed certificate printed on paper, Exhibition view of ‘Breadcrumbs: Art in the Age of NFTism,’ curated by Kenny Schachter at Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne // Photo by Simon Vogel

William Kherbek: Could you speak to us a bit about the historical and referential background of ‘Certificate of Inauthenticity’?

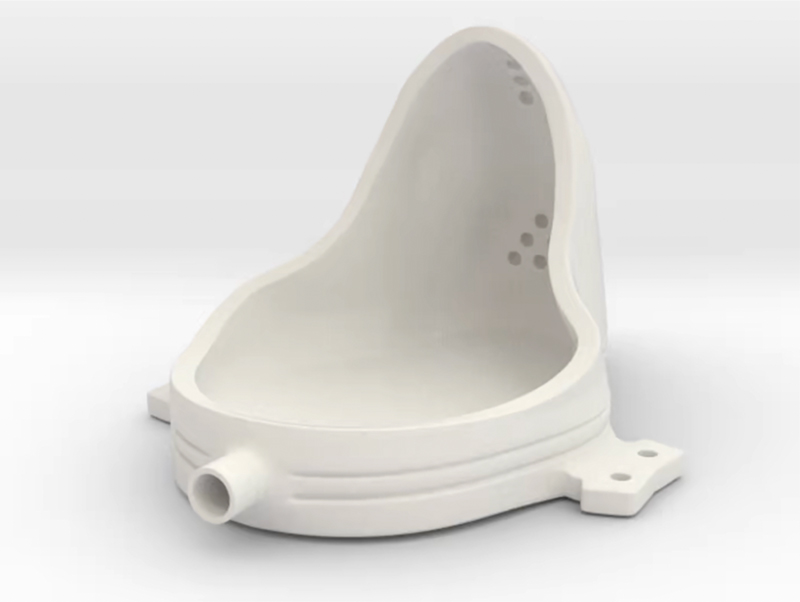

Rhea Myers: ‘Certificate of Inauthenticity’ came from a series of projects that I did starting with commissioning some awesome 3-D modelling artists called Christine Webber and Bassam Kurdali to model objects which had become effectively trademarked and taken out of the commons of artistic reference: if you see a balloon dog, you think of a particular artist; if you see a urinal, you think of a particular artist. This was part of a long series of projects around free culture, free software, making things accessible to people to use. Those models were released under a Creative Commons licence, which allows anyone to do what they want with the work.

Rhea Myers (Commissioner), Chris Webber (Copyright), ‘Urinal,’ 2011, 3D printable digital model from the series “Shareable Readymades.” This model is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License // Digital preview by Chris Webber.

Rhea Myers, ‘Certificate of Inauthentcity’, 2020, Digital File // Courtesy of the artist

I think the underlying impetus was not just the economics, but the justice of blue chip artists going to incredibly skilled artisans and saying, “hey, can you make me a perfect reproduction of this particular model of urinal?” or saying, “here’s this photo of some puppies, I want you to make it in 3-D in this colour scheme out of wood. Then I’ll come back in six months and sell it for millions of dollars, but no one will know who you are.” Creative Commons licences were a nice way of reversing that trend. The artists kept the copyright on the items that I put my attribution on. Then Furtherfield, a gallery in the UK I do a lot of work with, wanted to show and sell them, and I said the whole point of them is that you can’t. So what I did was to take a Sol LeWitt certificate of authenticity from his wall drawings, whited out his details, wrote in the details of my stuff, and signed it. This made it valuable in some way, because it was an assertion by the artist’s hand.

When the “rare art” scene emerged, I was interested in how it related to the anxiety of authenticity that haunts the contemporary art world. Everyone is terrified of owning a fake. Items get pulled from auction. People find a Pollock in a dumpster and their immediate thought is “oh, it’s fake,” not a fire sale that’s gone horribly wrong! As every non-art-world observer will happily point out, you would be hard-pressed to express the difference in aesthetic quality, intensity, or competence between the Pollock you find in the dumpster versus the capital an experienced artist can make by flicking paint at a canvas. This brings us back to the idea of genealogy—usually patrilineal—and the horror that someone, or something, that is ostensibly part of the family might sneak in and upset the value underwritten by art history.

Rhea Myers, ‘Artwork of the Century,’ 2016, 3D print with laser-printed certificate // Photo by Bruno Martelli

WK: This term you use, “the anxiety of authenticity,” is very much at the heart of contemporary concerns about value. There are different ways cultural capital accrues in digital spaces, sometimes it’s through presence, sometimes through a kind of performativity, sometimes through exclusivity-based blockchains, trustless relationships. Are there things you wanted to challenge in relation to this wider digital culture?

RM: With digital art, my slightly cynical experience of it is that we went directly from “oh, computers can’t make art” to “oh, all art is post-internet now. Why would you be interested in the place a computer has in this collage, or even this painting?” The constant denial of the critical possibility of using computers even as we have entered the age of social media has been very interesting to watch.

I don’t want to oversell this in ‘Certificate of Inauthenticity’ because it wasn’t what originally went into it, but this idea of a singular true authentic self that can be both economically and socially exploited by trusted third parties, by intermediaries, by social media, is one that falls apart at the first touch. I like danah boyd’s writing on how we present different facets of the personality to different groups, or the idea of code-switching from African-American studies. The idea that you have a singular identity is very very silly. For me, the internet is very much a site of identity play, not of freedom from identity in the naive sense, but somewhere where you can be another self.

The original cypherpunk impetus behind Bitcoin was very much that your identity is concealed and multitudinous behind the cryptographic identity that you use when you transact with someone. All you have to know is their address. The original vision for Bitcoin was you’d use one address per transaction to encourage anonymity. It helped the marginalised access capital that they couldn’t otherwise. Yes, it would be better to solve problems of housing, access to medicine, and everything else, but whilst we’re working on that, not having to reveal who you are when ordering meds from Canada or whatever is a useful facility.

With ‘Proof of Existence’ (2014) I put the hash of my genome on the blockchain to prove that at least someone with the same genes as me has existed since 2014. Later on a company wanted to do the same thing for real, and I was like “if an artist has done it, then there’s probably a bad reason for doing it for real, so no.”

Rhea Myers, ‘Proof Of Existence,’ 2014, Bitcoin Transaction // Image courtesy of the artist

WK: Another work of yours shown recently at Panke Gallery, ‘Tokens Equal Text’ also explores web-based communities, in this case musical communities interested in vaporwave. Could you speak about the background of this work, and the ways you explored authenticity and cultural specificity with it?

RM: I got interested in Vaporwave culture online, it’s sort of camp nostalgia for lost promised futures of plenty expressed through the iconography of consumerism. The sound of that promise breaking down in the music fascinated me, as well as the art that accompanied it, which is very sample-based, like the music. It makes use of everything from 1980s airbrush illustration styles, analogue video glitch aesthetics, and the whole postmodern Venus-in-shades thing, to computer games like ‘Ecco the Dolphin.’ I certainly don’t want to present it as mere nostalgia; it becomes an expression of political frustration: “our parents were promised this, but we’re not going to get it”.

What really just locked me in on this was the question asked again and again on Vaporwave message boards: is this aesthetic? And I absolutely loved this, because it’s the underlying question of art and art theory and criticism. In this context it doesn’t mean, “is this an object with any aesthetic value?”; it doesn’t mean “is this any kind of aesthetic at all?”; it means, “can we recognise the value of this within our common-law-style extensional aesthetic?” And this brings us back to the problem of ownership; all the imagery that Vaporwave art uses was taken from elsewhere, be it 3-D model catalogues, old album covers, clip art found on the internet.

There are three largely irreconcilable views of art that we bump into: there is the artist/art-historical view, there’s the legal/copyright view, and there’s the technological/pixel-level view. And each of these has different ideas of what “originality” is, and, hence, very different ideas of what authenticity and ownership mean. Vaporware is art-historically original and technologically wonderful. But from a copyright point of view, there’s nothing original at all in it, because the things have been used without authorisation—there’s nothing to own.

Rhea Myers, 2021 // Portrait by Kristy Powers

WK: What do you make of the current furore about NFTs and their status as “authentic” fine art?

RM: I’ve always seen the critical and developmental possibility of an encounter between art and technology, in this particular case between critical art and blockchain technology. The clock’s been ticking for a while on cultural and economic closure around this technology. And we’re only just getting past the point where pointing and shouting at blockchain stuff is the most rewarding option for most people.

Much of this shouting is clawing toward recreating critiques that people working within the blockchain space have already made, and that they have acted on in order to create new systems. But at the same time the people inside the crypto scene who have popularised this technology have only rarely had any connection to art history in a productive way. At the moment I’m not convinced that the people critically evaluating the work have learned how best to deal with any of that, and I include myself in this criticism. If we can work that out then we’ll have a much better understanding of how NFTs fit into fine art and vice versa.