by Nadia Egan // June 14, 2022

This article is part of our artist Spotlight series.

Perception stands at the centre of Elín Hansdóttir’s work. Focusing on immersive, site-specific installations, the Icelandic artist constructs unfamiliar and seemingly displaced spaces that compel the visitor to focus on the reception of their surroundings. In forefronting the bodily experience, her work investigates both the perceived and subconscious content of space and emptiness.

Since childhood, Hansdóttir has been fascinated by the structural composition of a given space. Recounting her first experience in an amusement park funhouse, she tells of how her “mind was blown” by the concept of a space not conforming to a traditional arrangement. Now as an adult, she focuses her artistic career on reconstructing similar experiences. From lengthy passageways leading nowhere, to makeshift models in perplexing dimensions, her work forces us to address our predetermined ideas of space and reality.

Elín Hansdóttir: installation view in ‘Long Place,’ 2005 // Photo courtesy of the artist

One of her first large-scale installations, ‘Long Place’ (2005), addresses such predeterminations. Inside the walls of Edinborg House—an edifice from the 1890s in Ísafjörður, a small fishing village in the north of Iceland—stood a 150 metre long corridor-like structure. Spanning the length of a football field, the pathway looped left to right, up and down, before funnelling the visitor back out the other side. Despite the rural surroundings, the installation’s bright white-washed walls inched closer to that of a futuristic sci-fi movie and quashed the first of the visitors’ expectations for what lay beyond the front doors. Voyaging round each twist and turn, anticipation arises for what could come next; but the answer is always nothing. The purpose of Hansdóttir’s ‘Long Place’ was never to provide a finished product, but rather to explore what goes through the visitor’s mind while traversing through this seemingly purposeless space.

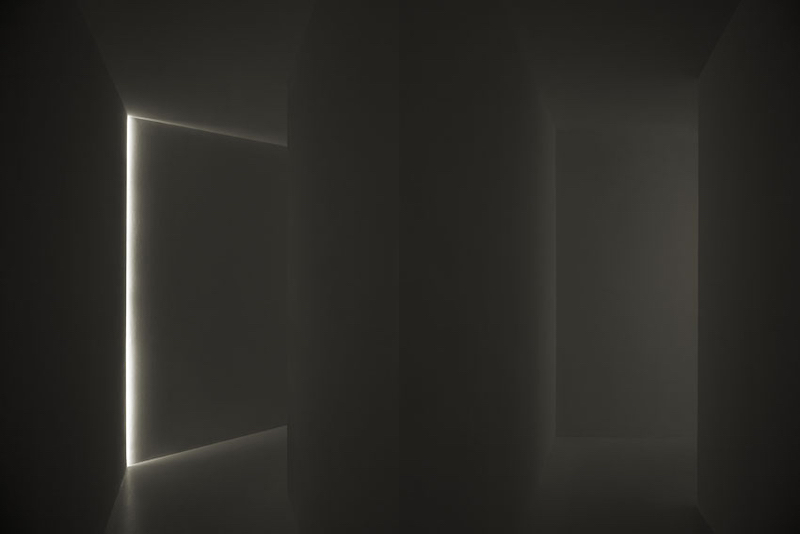

Elín Hansdóttir: installation view in ‘Path,’ 2008 // Photo courtesy of the artist

In a similar fashion ‘Path’ (2008) further explored the bodily reaction to unfamiliar spatial circumstances. Now in the dark, the visitor was invited to walk through a blacked-out, single winding corridor, throwing them into the dark confines of a solitary experience. Small vertical and horizontal slits allowed in small chinks of light, yet the resulting shadows distorted the visitors view rather than aided it. Such an extreme situation naturally elicited extreme responses. While some came out elated, others swayed towards terrified, with one man physically breaking free before reaching the end.

Elín Hansdóttir: ‘Portal,’ 2020 // Photo courtesy of the artist

Elín Hansdóttir: ‘Portal,’ 2020 // Photo courtesy of the artist

Photography has also been a medium with which Hansdóttir has experimented. Continuing with the theme of spatial perception, works such as ‘Portal’ (2020) and ‘Fractal’ (2021) challenge our ability to make sense of space with the portrayal of strange, uncanny dimensions. In ‘Portal,’ one of William Morris’ intricate wallpaper patterns is applied to a model corridor, then photographed from the same angle in various scales. Beginning in its full, original proportions, the photographs slowly become distorted, with dimensions shrinking and expanding in a perplexing manner. For ‘Fractal’—a series of photographs made specifically for the gallery of the Reykjavik Art Museum that take the vantage point of a centralised, concrete pillar—a similar, bewildering visual experience arises. The artist constructed multiple replicas of the space in different scales, adding additional quadrangular pillars to disturb its symmetry, then printing photographs of each replica in identical dimensions. While the proportions of the photographs stay the same, the model does not. The high resolution and identical dimensions of the images makes the distortion difficult to spot at first, yet our mind persists in telling us that something isn’t quite right.

Elín Hansdóttir: installation view in ‘Fractal,’ 2021, six archival inkjet prints, spatial intervention (columns) // Photo by Vigfús Birgisson

Now taking part in a residency at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, Hansdóttir continues with the exploration of perception in her latest show ‘Eigenzeit.’ Reminiscent of the spirograph drawings many know from childhood, a colourful guilloche pattern is printed onto translucent fabric and hung in semi-circles around the exhibition space. As an extension of her previous photographic explorations, large-scale images of the fabrics serve as a puzzling addition. Using the same fabric seen in her hanging installation, Hansdóttir produced small paper models of the exhibition space. While the photographs appear as ‘normal’ documentations of her work at first, the uncanny proportions soon become evident. With the shrunken interior against the full scale pattern of the fabric, the viewer begins to recognise the abnormalities and challenges posed to their initial conceptions. Although Hansdóttir’s previous works have often been sturdy and robust, ‘Eigenzeit’ is delicate and soft, with the accompanying gold-plated clovers dotted around the walls further augmenting this impression. Discovered while out walking her dog, the artist developed an obsession of sorts in finding these four, five or even six-leafed clovers. Although the mutated plants could have a simple scientific justification, their discovery remains a special message from the universe for Hansdóttir and their meaning one that she continues to question.

Elín Hansdóttir: installation view in ‘Eigenzeit,’ 2022, printed organza // Photo by David Brandt

Elín Hansdóttir: installation view in ‘Eigenzeit,’ 2022, gold plated clover // Photo by David Brandt