by Nina Prader, photos by Tina Linster // July 8, 2022

The sign above the studio entrance reads “Video Inn,” written in all caps and now coloured by an 80s patina. There, we meet painter Elif Saydam, sitting on the steps of the former video store in Alt Moabit, a district of old West Berlin. The spectre of this movie rental remains and lingers like a friendly ghost. Posters of Hollywood femme fatales and crates of video tapes still remain in the shared space. The video store has not completely moved out yet and even seems to be moving back in, though not in the form of physical, video cassettes. The store has morphed into a living archive of ideas, shape-shifted into a collective artist studio space.

However, no bohemian artists are to be found here, just diligent cultural workers, labouring from nine to five, seven days a week. “This place is like a nunnery,” Saydam jokes, “we expand and contract here, according to need.” Their latest works were produced in the front of the shop in a room with a very big window and recently exhibited at Tanya Leighton gallery. Today, fellow Städelschule alumni, José Montealegre, is soldering copper into intricate leaves for a sculpture.

Saydam’s extensive collection of bristle brushes, oil paints, and archive of cultural ephemera have migrated to what used to be the porn section of the video cassette store. Here, their practice flowers amongst plants and other creative comrades, between the dust of their studiomate’s woodwork and bike grease, fueled by desire, curiosity, and time spent in contemplation. How the images find their way onto the canvas is, at first glance, a mystery. However, the longer one is surrounded by Saydam’s wallpapering of knick-knacks and Tupperwares filled to the brim with odd souvenirs, one begins to notice how objects repeat themselves, create dialogues, and react to each other. Pencilled on the studio wall, the title of their recent show at Tanya Leighton gallery, ‘F*rgiveness,’ reads like an expletive, but appears as a whisper or residue. Forgiveness is reconfigured as an ambivalent notion, not of submission but of retaliation.

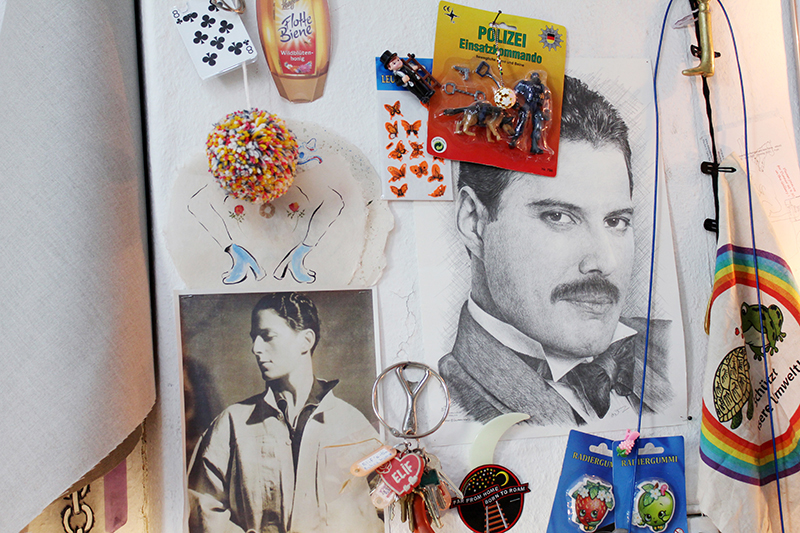

Though Saydam’s work is often regarded through a lens of the ornamental and decorative, the source imagery gracing the studio walls is evanescent. Not a direct reference at all, the visual signifiers seem very distant from what makes its way onto the canvas, like memories peeling off the walls. Saydam paints while speculating, “what if the audience are grandmothers, teenagers, and/or homosexuals.” After long flaneur walks or cycling through Berlin, archives of digital phone snapshots and odd objects are collected, sometimes ink-jet printed onto T-shirt foils, then melted directly, and unforgivingly, onto the canvas. Later still, they are embellished with painted patterns. A red sofa for dreaming and naps stands in the studio corner. A fur fox stole serves as a pillow while a found sketch of Freddy Mercury smirking like the Mona Lisa watches over the studio. Source images of patterns such as a tooth, cartoon character citrus fruits, an absurd toy figurine of a cop still in its plastic shell as well as golden chocolate wrappers create layers of frou-frou on the walls. “A friend will give me a chocolate wrapper because they tell me, ‘this is so you’,” Saydam explains. This is how the best material fodder finds its way into their studio—gifted by friends or the streets of Berlin.

The logistics of aesthetics fascinate Saydam to the point of obsession. How can something be ornamental and challenging? How do motifs and patterns obtain signifying powers? If a banner hangs out of a painting like it would out of a Berlin balcony, shouting rainbows, the baby colours of the trans flag, or FCK AFD, can the slogan-like meanings be both vacuous and meaningful? “It could either be a commodified reference to sentimental righteousness, the palette of which fits nicely, but, even if it effectively belittles the processes of embodiment and exclusion it refers to, it also works as a casual symbol by which people can recognize each other,” notes writer Maxi Wallenhorst in an essay on Saydam’s work entitled ‘Tidbits for Diminutive Materialism: The Snack, the Artist, and the Outlier.’ In the lyrical and theoretical text, the snack becomes a critical theory to understand how tasty aesthetics musing on cuteness bite back. The decorative lemons in the painting ‘Making Lemonade’ (2021) juxtapose ornamental gold leaf lemons with the German juice pack ‘Durstlöscher.’ They contain the wit of a well-crafted meme with the ambiance of an old-timey miniature painting. Viewers consume the work as they would a satisfying snack. But what is being thirsted for, or whose desire ever really quenched?

Also an independent novelist published by Broken Dimanche Press, Saydam maintains a writing practice that, though intimate, is a part of their painting process too. Many paintings’ titles have a double name. The addition of “also-known-as” opens a door into another reading, doubling the content’s possibilities. Often the titles of series such as ‘The Landlords’ exist before the work itself is made. Though the titles are catchy and the signs reference political ideas, Saydam comments, “I would not say my work is explicitly political but it does push an agenda.” Saydam is inspired by American realist painters though transfers their visual vocabulary into a European setting. What would be diners or gas stations in America are Spätis, laundromats or casinos in Berlin. Against the wall where usually a canvas would hang, leans an OPEN sign from a Biergarten. Similar to the nostalgic video store vibe, the sign is like a portal into another dimension. A recurring theme in their work, the corner store or Späti is a motif and cultural gateway in Berlin that also exists in Paris, Istanbul, and Montréal, but with different names—not to mention that they could be interpreted as a subtle critique of capitalism and serve as alternative gathering spaces or sites of refuge. In the painting ‘Alles Fantasy aka Meet me Later or Never, Really’ (2022), a red stop-sign-like sign reads “Spät Kauf,” the universal symbol for after-hour shopping.

So what does it mean to paint amidst the debris of capitalist realism and digital consumer culture? In Saydam’s studio, seriousness and comedic relief hang out in conversation. The idea of the artist as worker, for example, is to be found in the gimmicky twinkle of a casino logo; the cartoon-star sticker sports the names of exhibition funders. Its eyes have bulging red veins, shining bright and burning out. Everything that glitters is not gold. Then again, the value placed on art and commodities is arbitrary, but specific. The candy wrapper trash starts to have a similar shimmer to the gold leaf embellishments on some of the canvases. The value of the signs adapt to each other. “To me, this is camp, not kitsch,” states Saydam. The difference? Camp exposes the aesthetic hierarchies and blends them into the everyday. Tenderly, Saydam points out that this transformation from artefacts into culture is something ”queers and immigrants understand the best.” Trinkets become souvenirs, as was the case in their parent’s collection of memorabilia in Canada—reminders of their Turkish heritage. Memories of places and identities adhere to objects like metaphoric star-dust, a doorway into another realm, a code representing and dismantling itself all at once.