by Reuben Holt // Sept. 23, 2022

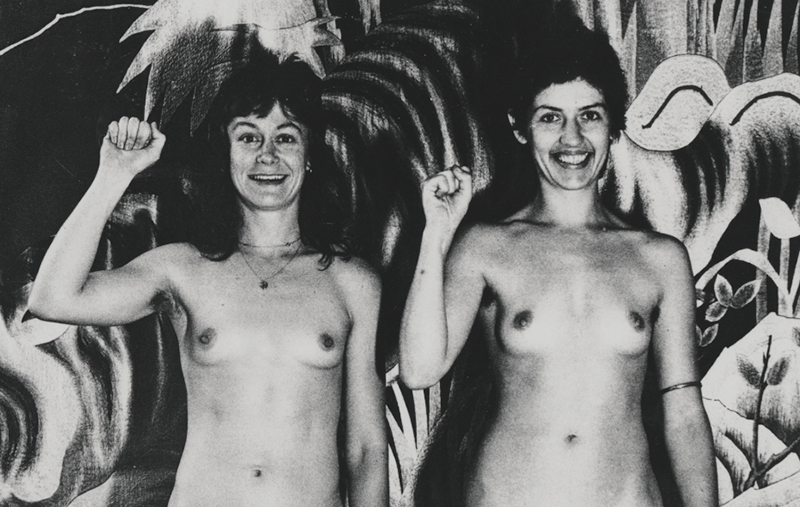

Somewhere out of view, we can hear the urgent ringing of an incoming phone call. Two young women are applying makeup, gazing into what seems to be a mirror. But this is not a L’Oreal commercial. The women begin to smear the red lipstick and blue eye shadow across their faces. The ‘mirror’ is revealed to be a camera lens, and the camera is rolling. The two women are not just the subjects of the filming taking place. They are in control of the action.

Robin Laurie and Margot Nash: ‘We Aim To Please,’ 1976, film still // Courtesy of the Artist

‘We Aim To Please,’ inked in marker pen by filmmaker Robin Laurie on the bare torso of fellow filmmaker, Margot Nash, during its title sequence, is a 1976 Australian short film that celebrates women as they see themselves. Intercutting erotically charged moments of physical comedy with snippets of conversation, visceral images and political statements, the film is a love letter to female pleasure. With a sly self awareness, Nash and Laurie expose and parody conventions of filming and editing, which, then as now, have overwhelmingly assumed the viewpoint of a male audience.

Events of recent years have ignited new interest in the film, as male violence against women remains rampant and fresh battlelines are drawn around the litigation of women’s sovereignty over their own bodies. ‘We Aim To Please’ recently screened as part of a three-month exhibition at Berlin’s House of World Cultures (HKW). A retrospective, ‘No Master Territories’ celebrated films by women dealing with gender, spanning six continents and featuring hugely influential innovators of cinema such as Agnes Varda, Chantal Akerman, Barbara Hammer, Mona Hatoum and the Ukrainian-born Maya Deren. In revisiting the period of the 1970s to 1990s, the exhibition paid homage to this important cinematic work while building connections with the challenges of the present. From May 9 to July 12, 2023, this Berlin-curated exhibition will make its next stop at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, where women face the ongoing fallout from Poland’s sweeping 2021 ban on abortion and vanishing access to female birth control.

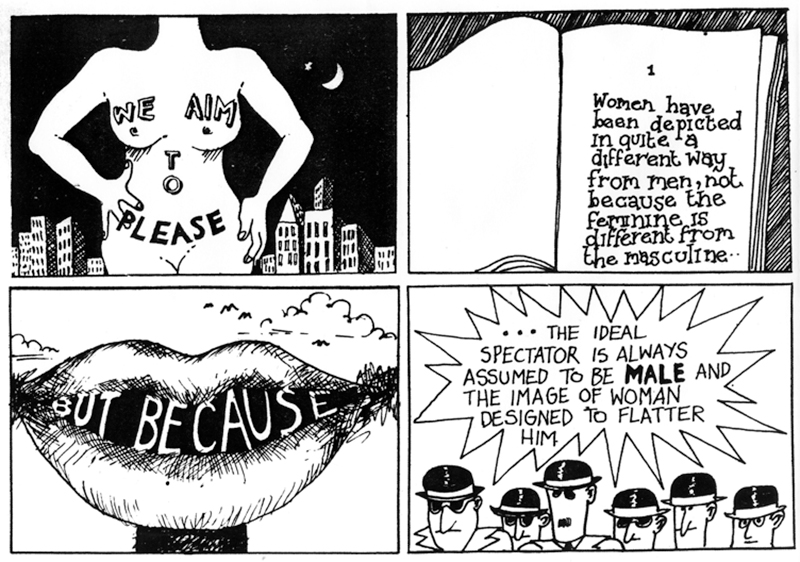

Carol Porter: Promotional material for ‘We Aim To Please,’ 1976 // Courtesy of Margot Nash

“I think there’s a resurgence of feminism at the moment,” says Margot Nash, a fixture in the Australian film industry who has garnered accolades for her screenwriting and directing. “The #MeToo movement was incredible the way it outed the extraordinary behavior of men who had such a sense of entitlement when it came to women’s bodies.”

‘We Aim To Please’ wears its influences loud and proud, with a lip-synching sequence that directly quotes critic John Berger. Berger rose to cult-stardom with the then-controversial 1971 BBC series ‘Ways of Seeing,’ a groundbreaking take on the nude in Western art. The film’s humour and dramatic moments reflect Nash and Laurie’s backgrounds as theatre actors and Laurie’s comedic talent as a circus performer. ‘We Aim To Please’ blurs boundaries between action and audience, memorably, when a ripe, juicy tomato is hurled into the air and heads straight for the camera lens.

Nash and Laurie weren’t too concerned about hiding the fun they had during the making of the project. “I have memories of filming it and laughing a lot. Some of that laughter was recorded and it’s in the film,” Nash says. Her fondest memories came from her recording and editing experiments which became the soundtrack for the film. “At night, I had all these microphones positioned outside the windows and the door of the house where I was living. I would sit there listening to different feeds from microphones coming in, people talking, catcalling and wolf whistling.” This became rich source material for evoking the anxieties of the women protagonists, as well as the film’s ever-present spectre of male violence.

Robin Laurie and Margot Nash: ‘We Aim To Please,’ 1976, film still // Courtesy of the Artist

The project’s shoestring budget meant that its creators had to be inventive to access the resources they needed. Their filming schedule was dictated by small windows of free access to otherwise unaffordable equipment borrowed from Nash’s day job as a camera assistant. “I’d ring Robin up and say ‘Come over! I’ve got the camera this weekend!’” Nash recalls.

Despite these limitations, a negligible budget meant freedom from oversight. “The film industry is very goal-oriented,” explains Nash. “Because it’s an expensive medium, they want a script so they know what’s going to happen. When you go out and shoot, you shoot to the script and it cuts off that element of play, it cuts off the opportunity to step into an unknown space. When it was just me and Robin with our shoe boxes full of plans and pictures and ideas, we didn’t know what we were going to get. Now that I’ve gotten older I’ve gone back to that way of working.”

Despite or perhaps because of Australia’s geographic isolation, Nash recalls a relatively small but highly motivated network of women making independent films, savvy to what their peers were producing elsewhere. “In America and certainly in London, too, there were radical film working groups. We didn’t feel so isolated because we were part of a broader film community in Australia and that community had outreach all over the world.” This spirit of mutual curiosity and fascination is captured in photographs at ‘No Master Territories,’ with many of the exhibition’s represented artists pictured together at film festivals in who’s-who-style lineups.

“A lot has been gained since 1976 but we’re also seeing a rise of autocracies and the far right,” Nash says. She reflects on the shockwaves sent by the recent US Supreme Court decision to strike down the verdict of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 court ruling which enshrined legal protection for American women seeking abortion. “Women are having to really fight for basic rights to their own bodies. I think ‘We Aim To Please’ still has something to say.”