by Moses Hubbard // Oct. 15, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ’OIL.’

Arguably the greatest untold story about oil is its role in the production of plastic. During WWII, oil replaced coal as the main raw material in chemical manufacturing, thereby ushering in an era of commodity production on a scale that was previously difficult to even imagine. Oil can be refined into ethane and propane, which can be turned into pretty much anything—not just water bottles and tupperware, but synthetic fibers, piping, detergents, packaging, fertilizer, kevlar, even acrylic paint (in a roundabout way, acrylic, too, is a type of oil paint). Plastic, which is also to say oil, is literally woven into the fabric of everyday life—all the more reason to tell this story as clearly and cogently as possible.

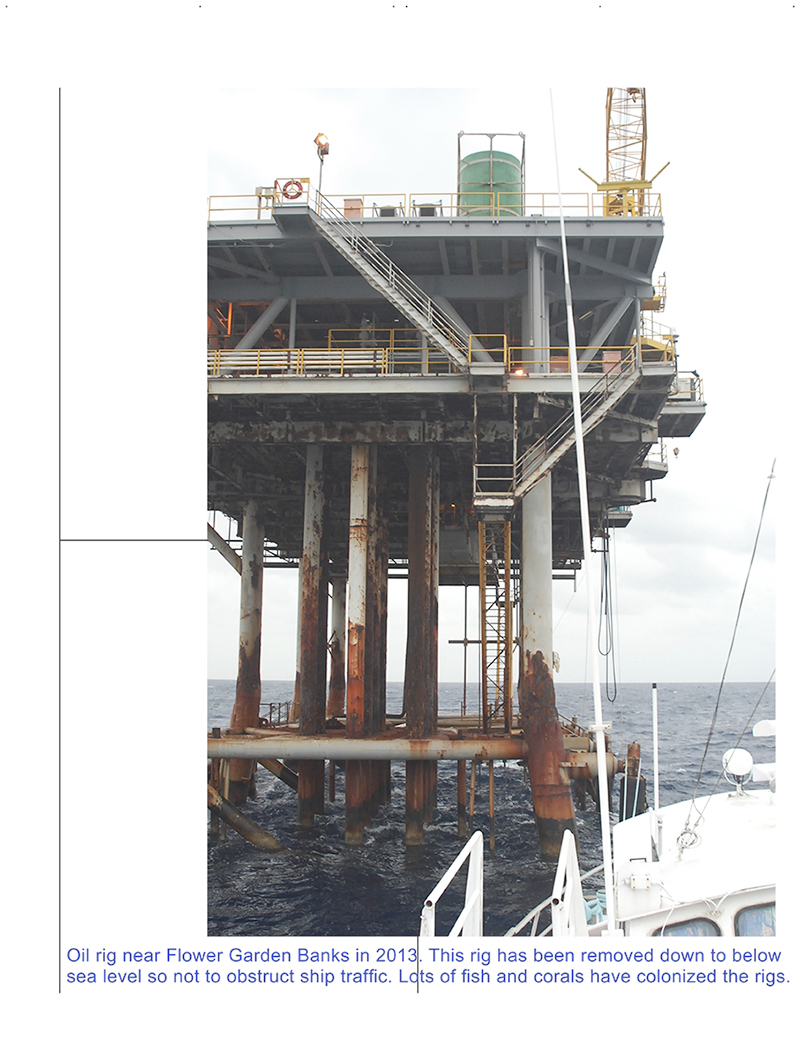

Giulia Bruno und Armin Linke: ‘Earth Indices. Processing the Anthropocene’ (2020 – 2022) // Courtesy of the Artists, photo by Kristine DeLong

‘Earth Indices,’ an exhibition by Giulia Bruno and Armin Linke at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) attempts to do just that. It provides a window into scientific research on the traces humans have left on our planet. Since 2019, the artists have collaborated with the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), an interdisciplinary team of academics that was formed to determine whether human production has initiated a new eponymously named geological era. Proponents of the Anthropocene argue that the Holocene Era, which began in 11,700 B.C., ended some time around the 1950s. This period corresponds with the advent of the Great Acceleration, the ongoing exponential growth in human production and resource extraction, largely thanks to plastics and other petrochemical products. The bulk of the AWG’s research over the past decade has been devoted to identifying markers of this new era, including radiation, carbon byproducts, concrete, aluminum, fertilizer, and microplastics, to evaluate whether the earth’s geology has in fact been fundamentally transformed by human activity.

If the Anthropocene Era is officially recognized, it will mean that, for the first, and perhaps last, time, geologists are studying a time period that emerged near to their own lifetimes. Mindful of this synergy, Bruno and Linke set out to develop an exhibition that emphasizes the human aspects of the research process. As the artists write: “The ‘Earth Indices’ installation is conceived as an artistic exhibition but also as a tool for a performative and active reading of the AWG scientists’ work.” Part of its stated function, then, is to present the scientific process as embedded within social and material systems. This itself is an echo of the overarching principle of the concept of the Anthropocene: that it is no longer helpful or accurate to imagine a dichotomy between human systems and the world we live in.

Given the extent to which Bruno and Linke are aware of the significance of this program, and the effort that they have made to define a useful position within it, ‘Earth Indices’ itself falls remarkably short. The layout of the exhibition makes it physically difficult to look at many of the images on display. The installation consists of 135 inkjet prints and 31 dyptics hung on what is essentially a metal scaffolding in the main lobby of HKW. The scaffolding runs through several large columns, which obscure the prints and interrupt the process of moving through them. Other prints are difficult to see because they are hanging behind balconies. Several pairs, for no clear reason, have been installed on single sections of scaffolding above all the other images. By frustrating the process of looking, the installation detracts from its content. The work begins to feel like an afterthought, or worse, a nuisance.

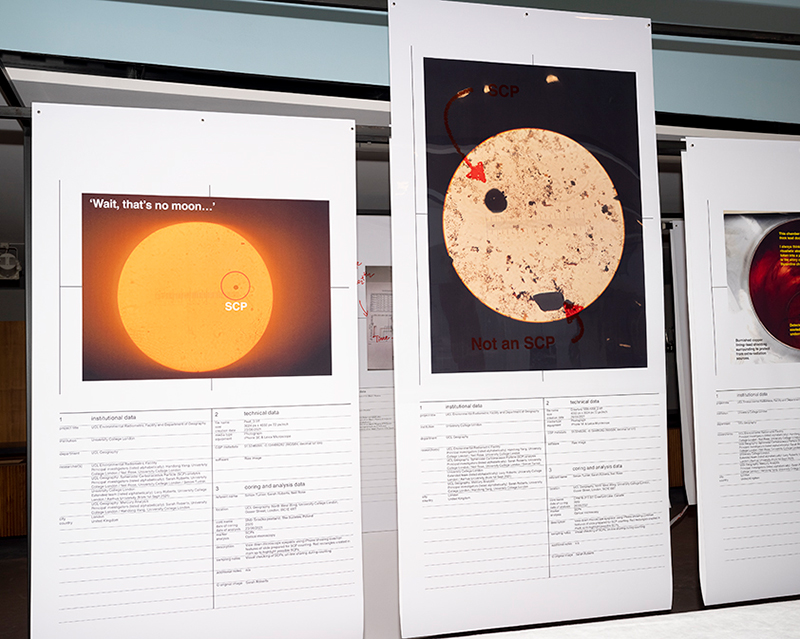

Giulia Bruno und Armin Linke: Installation view of ‘Earth Indices. Processing the Anthropocene’ (2020 – 2022) // Courtesy of the Artists

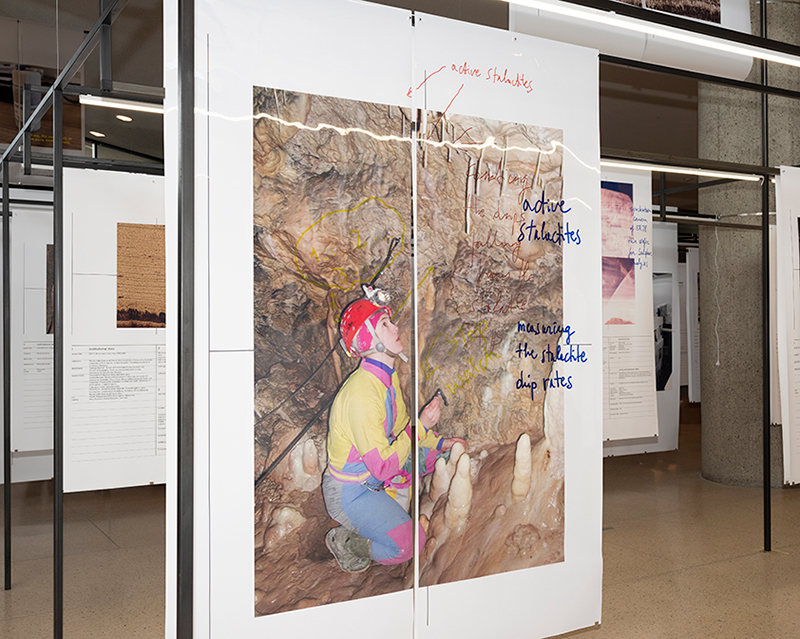

Giulia Bruno und Armin Linke: Installation view of ‘Earth Indices. Processing the Anthropocene’ (2020 – 2022) // Courtesy of the Artists, Photo by Katy Otto

The prints picture photographs and data models produced by the AWG researchers. Underneath each image is a table of metadata, and some images are accompanied by overlaid annotations from members of AWG. These overlays provide the most charming moments in the exhibition. One note explains the process of differentiating between plastics and nonplastics, which is called a “spectroscopic method.” “The name might sound complicated,” it says, “but it involves the splitting of light into its constituent wavelengths—it is pretty much like a prism splits light into a rainbow of colors!” Unfortunately, such high points are few and far between. Many of the images are not annotated, and nowhere else in the exhibit is there an explanation of their contents. There are also formal inconsistencies in the images displayed. Certain overlays are printed directly onto the images, while others are printed on transparent sheets that hang in front of them. The contents appear to have ommissions as well. For example, the parenthesized text in one diptych reads “(they can live for INSERT years).”

Giulia Bruno und Armin Linke: Installation view of ‘Earth Indices. Processing the Anthropocene’ (2020 – 2022) // Courtesy of the Artists

The awkwardness of the space would be easier to excuse if the scaffolding were a permanent fixture of HKW lobby, or if the artists were required to work with a particular number of prints, or even if they were simply unfamiliar with the space itself; none of this is the case. Bruno and Linke have been working at HKW for years. They selected the images themselves. The scaffolding and exhibition structure were thoroughly modeled before their installation.

A further point of confusion is the asymmetry in contextualizing material. Upon entering, you receive a 48-page exhibition booklet, which contains essays about the AWG, an interview with Bruno and Linke, descriptions of the research sites, and a selection of images from the prints. There is also a library of Anthropocene-related texts on the upper floor of the lobby, as well as a sprawling online publication curated by researchers at the Max Planck Institute. These materials are carefully written, thoughtful, and compelling, which makes it all the more disconcerting that there isn’t any information about the prints themselves. Clearly, an enormous amount of energy and thought went into the development of this program. Why, then, are the images themselves so inaccessible?

Giulia Bruno und Armin Linke: Installation view of ‘Earth Indices. Processing the Anthropocene’ (2020 – 2022) // Courtesy of the Artists

A sympathetic reading might be that, by making it difficult to view the prints and declining to impose interpretive schema on their contents, the artists force the viewer to confront the uncertainties and disheveled moments in the production of scientific knowledge. Describing the subjects of the prints, Bruno and Linke write: “As photographers and artists, we’re interested in seeing how all these instruments, not just the most spectacular ones, form part of the larger set of information and culture production. And, perhaps, we’re interested in destabilizing the hierarchy of spectacularity—in understanding where the image, the photography, fails.” Foregrounding the mundane aspects of major research is a worthy, if not particularly novel concept. However, the obscuring of images and information did nothing to inform a potential dialogue on how the image fails. In this case, the failure we are confronted with isn’t the “hierarchy of spectacularity,” or the image, or photography, but the exhibition itself.

Despite the fact that petrochemicals are projected to account for 30% of global demand for oil by 2030 and are already so deeply integrated into our world system that they’re one of the main markers AWG researchers tested for, their role remains marginal in popular discourse on oil usage. Part of the reason for this is that it’s hard to communicate scientific findings to the public, the collateral damage of which is clear enough that it doesn’t need to be explicated here. It’s disappointing, then, that a project tasked with bringing research into closer contact with its social and material constituents produces the opposite effect. The ‘Earth Indices’ exhibition closes on October 17. We can only hope that, if a similar initiative from the AWG follows, it will do more justice to the organization’s work.

Exhibition Info

Haus der Kulturen der Welt

Giulia Bruno and Armin Linke: ‘Earth Indices’

Exhibition: May 19-Oct. 17, 2022

hkw.de

John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10, 10557 Berlin, click here for map