by Julia Mazal // Nov. 3, 2022

Carlo Oppermann, born in Darmstadt but now a Berlin-based director, is showing his short film ‘The Art of Authenticity’ (2021) at Berlin’s Interfilm festival. His experience as a director of short films and commercials, where humor is often his signature, can be clearly seen in the advertisement format of his selected film for the German Competition section of this year’s festival. Berlin is so well known for its rough and dirty aesthetic, that it has become a part of its urban identity. Oppermann’s film explores the day-to-day activities of a one-man underground department (the “Department of Urban Authenticity”) that works night and day to make sure Berlin keeps up its reputation as one of the coolest and most authentic cities in Europe. We spoke to Oppermann about the different layers of the film including authenticity, the urban identity of a city and gentrification.

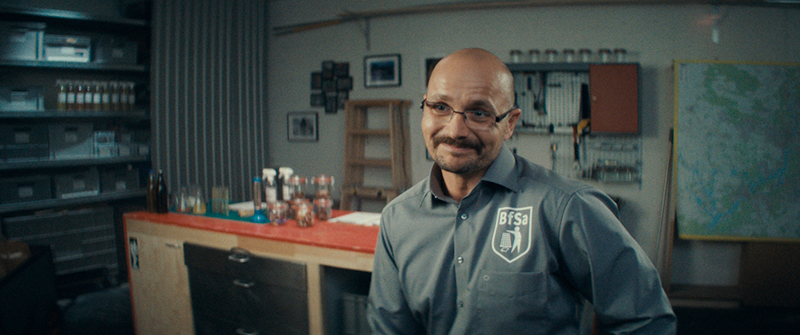

Carlo Oppermann: ‘The Art of Authenticity,’ (2021), film still // Courtesy of the Artist

Julia Mazal: What gave you the idea for the ‘Art of Authenticity?’

Carlo Oppermann: I love the idea that sometimes, when you stumble across something, maybe there’s a bigger story behind it, which happens to me a lot when walking around Berlin. For example, sometimes I would stop and wonder if there was a bigger story behind the trash spilled everywhere on the street, as if someone had gone out of their way to create this. Once I had that thought, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. So, for example, when people throw their mattresses out of their balconies and other people start to pile random stuff on top of it, I can’t help but think about the intention behind these actions.

JM: How long did it take you to film and which neighborhoods in Berlin do you find emblematic of this authenticity?

CO: We filmed for three days. While driving around the city, we didn’t have a specific plan, we would hop off, capture shots, then hop back on scouting for the right places. I had a few spots in mind, the obvious Berlin sights, like Brandenburger Tor. On the other hand, I also wanted to film the places that don’t have a specific name, but where many people live and walk every day. I live in east Berlin, so Ostkreuz. It is not necessarily an interesting place, but everybody knows there’s always trash on the street and many people live, work and walk through there. And then there are also those places that are famous for being a little dirty, like Kottbusser Tor, which, ironically, are now also the neighborhoods where people can no longer afford rent.

Carlo Oppermann: ‘The Art of Authenticity,’ (2021), film still // Courtesy of the Artist

JM: Do you think Berlin is losing its urban identity with all of the new development?

CO: The gentrification in Berlin is obvious, pushing out the people who made the place interesting in the first place. However, when I came up with the idea for the film, gentrification wasn’t necessarily what I intended to comment on, and maybe that’s better because it shines through more subtly.

Sometimes the people who move to Berlin misunderstand it a little bit. For example, if you move here and think the city is so great because of the authenticity in the street art, the culture, the clubs, the street food, etc., but then you take your SUV and drive to your financial startup every day, I don’t think you understand the city.

JM: By creating the Department of Urban Authenticity, are you humorously questioning what counts as authentic? Could it be seen as a critique of any kind of romanticization of filth or poverty?

CO: Usually, when I write something, I start with a topic that is important to me and try to make a film around that, but sometimes I think that can turn out to be a bit one-dimensional. With this film, however, I was inspired by just walking around and writing different ideas down.

The romanticization of existential problems happens a lot in advertising, where my background is. Many big brands use filth, poverty and the struggle to get out of it against all odds as a strong emotional message to capture the audience. However, the message is often empty and appropriated because there is never a deep dive into the socioeconomic problems surrounding these issues. This is sort of like poverty tourism. In many cases when people lack existential problems, they look for them in other places.

Carlo Oppermann: ‘The Art of Authenticity,’ (2021), film still // Courtesy of the Artist

JM: Why do you think authenticity plays such a big role in urban culture?

CO: These days to understand authenticity, means you are one of the good ones. Everybody’s afraid of going to a restaurant, telling their friends about it, and then, being told, “that’s so inauthentic.” Especially in advertising where I work, authentic is sometimes the most overused, meaningless word. There’s a place for it, but often it just gets thrown around. In big urban settings, where people compete with each other more, the striving for authenticity and individuality is heightened.

JM: Who does the Department of Urban Authenticity represent?

CO: It doesn’t represent someone specifically, but more like different character traits. For example, the German bureaucrat—the guy in a small department taking himself extremely seriously. When you go to get your passport renewed, they make it seem as if it’s the most important and complicated thing. German bureaucracy tends to produce these character traits that I wanted to incorporate into the protagonist.

Carlo Oppermann: ‘The Art of Authenticity,’ (2021), film still // Courtesy of the Artist

Another trait I wanted to use was that of people who want to call everything art to give it more value, and if anyone questions it, it means they don’t understand it. I find the “art” label interesting because I often wonder what makes something art rather than, for example, craft?

I also wanted to include the trait of the “storyteller.” There’s this part where the character in the film says, “actually, I’m a storyteller, there’s a story behind every installation or every piece of art I do.” Storytelling is something I find everywhere these days. Whether you’re developing an app or working in the stock market, everybody’s a storyteller. I find it funny because it immediately makes it sound important and deep when someone says, “there’s a story behind it.”

Festival Info

Interfilm

38th International Short Film Festival Berlin

Nov. 15–20, 2022

interfilm.de