by Jake Romm // Nov. 29, 2022

Icons are still produced and still function as objects of devotion throughout the Eastern Christian world, but today they are largely (mass) manufactured in the antique style, mere recapitulations of the old masters. It would seem appropriate that organized religion—which continues to suffer from the alternative and complementary modern crises of demystification and fanaticism—and its attendant cottage industries would, when crafting devotional objects, look back to the “glory days,” as it were. With the icon, it is both the saint and the time of the saints’ more widespread veneration that are honored—both God and a nostalgia for God.

But times have irrevocably changed, and while the mass reproduction of the old style may be the rule, icons were never a static medium, undergoing numerous thematic and stylistic changes and admitting a plethora of geographical variations. That this development has stagnated is as much a testament to the historical decoupling of art from religion as well as the decoupling of religion from society at large. But this does not mean the icon is a dead medium, or that it ought to remain static. There is still a sublimity, even a secular sublimity, to be mined from religious art, which is precisely the importance of Germany’s Klaus Hack.

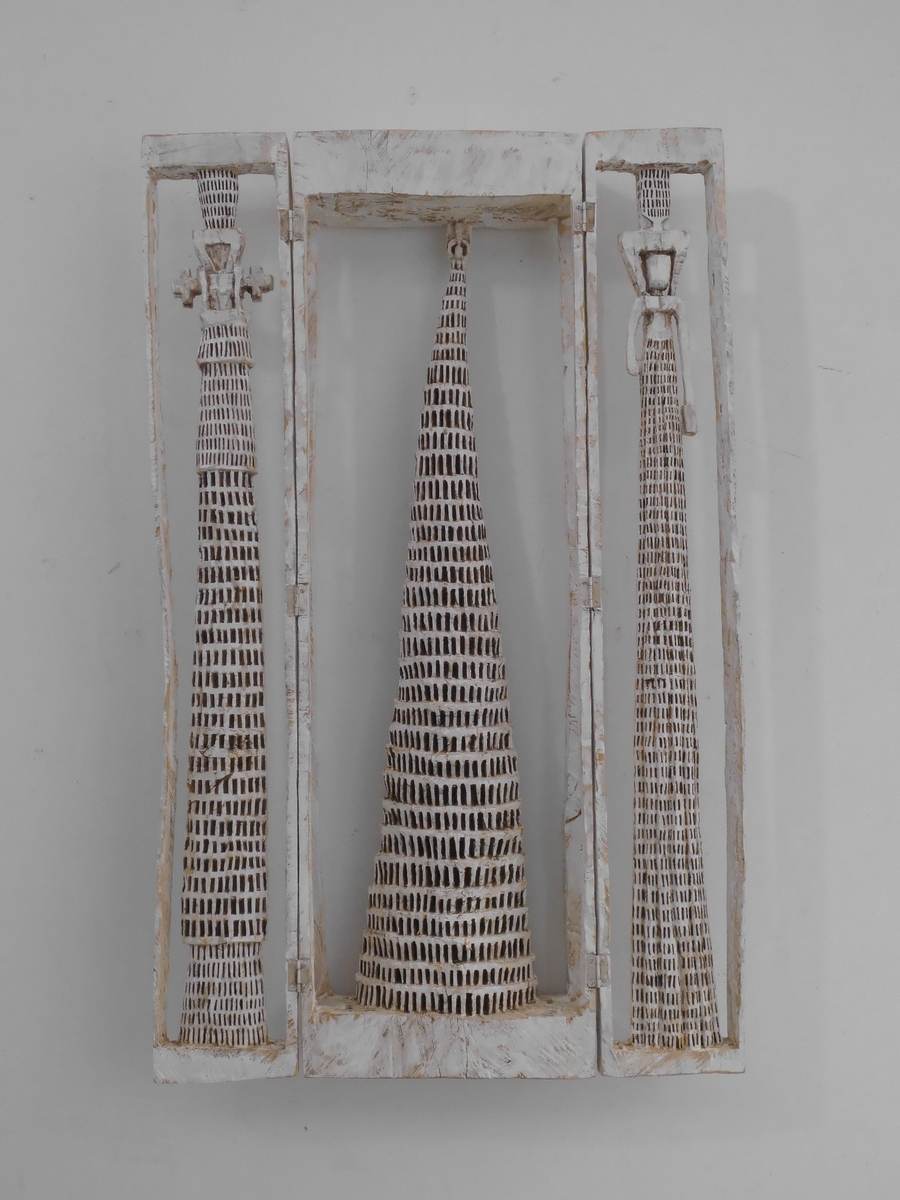

Klaus Hack: ‘Babel – Turm,’ 2012/2014, painted European beech, 263x45x49 cm // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Berlin

Hack’s ‘Einblick – Skulpturen, Zeichnungen, Holzschnitte’ (Insight – sculptures, drawings, woodcuts) is currently on view at Galerie Berlin until December 3. Born in Bayreuth, Germany in 1966, Hack is primarily a sculptor, woodcut maker, and, more quietly, an accomplished painter. While Hack’s work is not exclusively religious in theme, religion is a frequent subject of both his wooden and painted works and the primary focus of the works currently on display in Berlin.

It is disappointing that Hack’s work is rarely shown outside Germany (and never, by my count, outside Western Europe) because he deserves greater recognition than he currently enjoys. On the other hand it is entirely predictable—the work is intimately tied to the German artistic tradition, particularly gothic architecture and woodworking and German expressionism (which of course also bears some traces of the gothic).

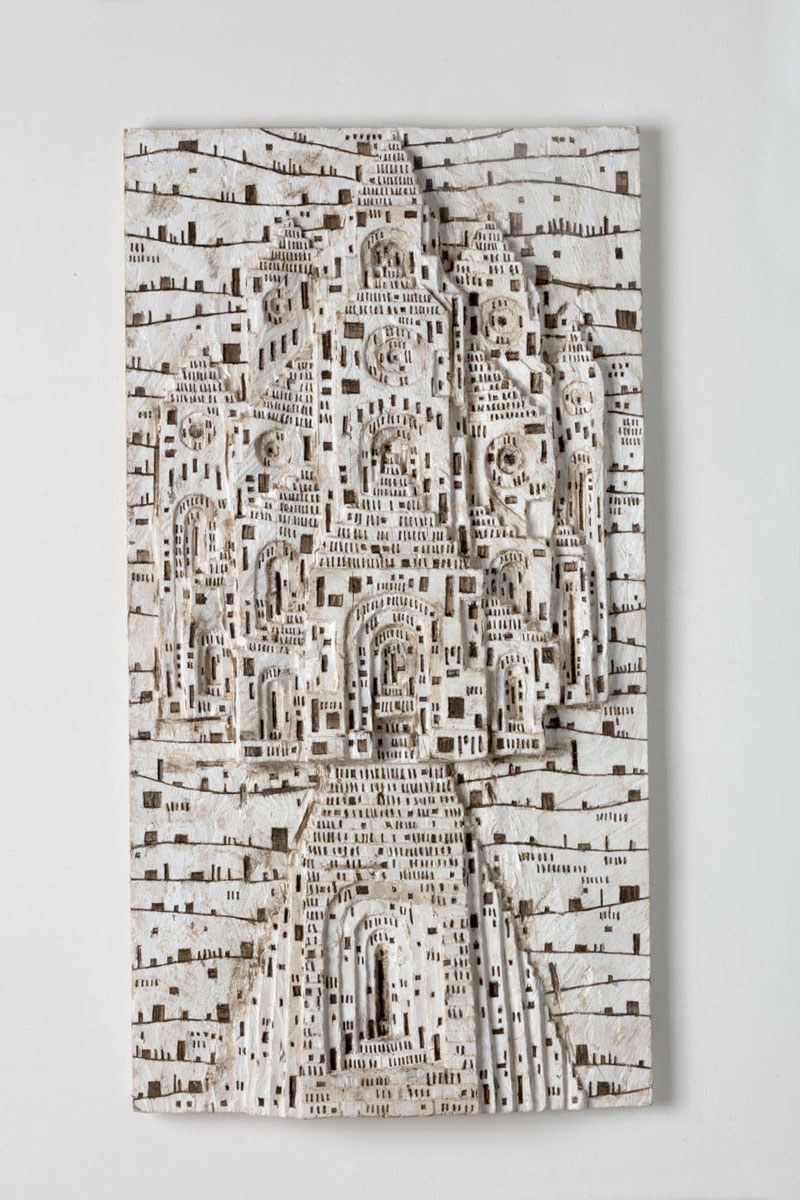

His sculptural work is exclusively done in rough hewn wood. The coarseness of the wood provides the sculptures a dynamic tension that lends them the appearance of being simultaneously unfinished and midway through the process of decay. The finished works give form to Sebald’s dictum that every monumental building contains the seeds of its own destruction. For all their roughness, however, they display an immense craftsmanship. The windows and spires of ‘Cathedral 2’ (2018/2019) or ‘Cathedral 1’ (2017/2019) have an almost filigree like thinness; the encased figures in ‘Standing Altar Figure’ (2017) mimic and elaborate on the large central tower in a meticulous miniature reproduction.

Klaus Hack : ‘Kathedrale 2,’ 2018/2019, painted pine, 130x68x9 cm // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Berlin

The sculptures, all lacquered in white paint, often take the form of altarpieces or are models of monumental, vaguely cultic structures. They almost all share a sort of honeycomb patterning, a spiraling vertical thrust studded with irregular openings. The buildings’ axes are always off kilter (particularly in the fantastic ‘Babel – Tower’ (2012/2014)). This irregularity combined with structures’ monochrome white strongly evokes the architectural renderings in the work of German Expressionist artists such as Ludwig Meidner or, another expressionist touchstone, Hermann Warm’s set design for ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.’

The figures in the paintings appear as half-remembered religious icons filtered through the undulating, de-structured visions of a dream. The spiraling Tower of Babel motif recurs, but now it is blurry, folded into indistinct figures. In ‘Untitled’ (year unspecified) it functions as the base for what appears to be an angel—not an angel as they traditionally appear in Western art, but as one of the terrifying many-eyed angels of the Bible. In another untitled work, the tower appears upside down, as both the pointed legs and ribcage of a bleeding Christ, flayed and suspended like hanging meat.

Klaus Hack: ‘Babel – Altar,’ 2010/2013, painted limewood, 122.5x76x14 cm // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Berlin

Hack’s use of sacred forms (altarpieces, in particular) and religious themes combined with his own personal aesthetic fixations could reasonably lead one to assume that his work is rather dated. But, on the contrary, Hack’s talent lies in his ability to mine new material, new forms, and draw new associations out of aesthetics that have, in any event, never really left us. His use of monochrome harkens back to and slyly updates the monochromy of German sculptural masters such as Tilman Riemenschneider, whose limited color palette was both an artistic choice and a financial necessity. Hack’s liberal application of white paint is both industrial and austere, but also, given the history of monochromy in German wooden sculpture, ostentatious and excessive—a subtle acknowledgement and subversion of the role of wealth in Catholic grandeur and mystery as well as a nod to the ways in which such grandeur and mystery has been mass produced and commodified.

Hack’s deployment of religious themes along with his formal fixations admit a number of interpretations, but principally two conflicting ones: is it a desacralization, a mortification of the church and christianity? Or is it a re-sacralization, a nevertheless monumental austerity intended to return to the religious a sense of the sublime, a positive-terror that the splendor of the cathedral has, by its beauty and ubiquity, ceased to inspire?

Perhaps Hack’s work is an attempt to produce the modern icon. With the incorporation of industrial and modern materials as well as a shift in size, he turns to early Christianity (when methods of religious representation had not yet split so decisively between East and West) through the foggy lens of history. In doing so, he succeeds in shrinking the divine down to the human scale, a scale at which the work may inspire mystery and devotion not through the brute force of size and splendor, but through the mastery of the artist and the opaque, ineffable interiority of the work.

Exhibition Info

Galerie Berlin

Klaus Hack: ‘Einblick – Skulpturen, Zeichnungen, Holzschnitte’

Exhibition: Oct. 20–Dec. 31, 2022

galerie-berlin.de

Auguststraße 19, 10117 Berlin, click here for map