by Matteo Calla // Dec. 20, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ’ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE.’

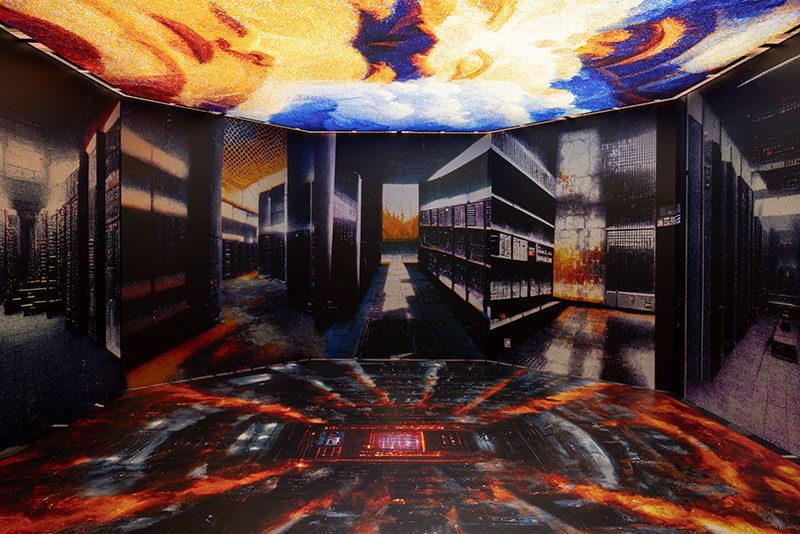

In a sense, the set-up of Sprüth Magers’ second floor gallery space in Mitte Berlin, in which Jon Rafman’s ‘Counterfeit Poast’ was exhibited this Fall, wasn’t so different from the neoclassical rotundas of the Schinkel Pavillon, where the artist’s work can still be seen until January 22. A wallpapered, octagonal room with large-scale portraits mounted on all sides, it looked like the inside of the Greek tholos, the circular kind of temple made famous at Delphi. The mystical connotations extended to the title of the presentation, ‘Chapel,’ but in place of images of the gods, however, this chapel featured a new type of secular art: a series of uncanny posthuman figures generated using a text-to-image AI algorithm.

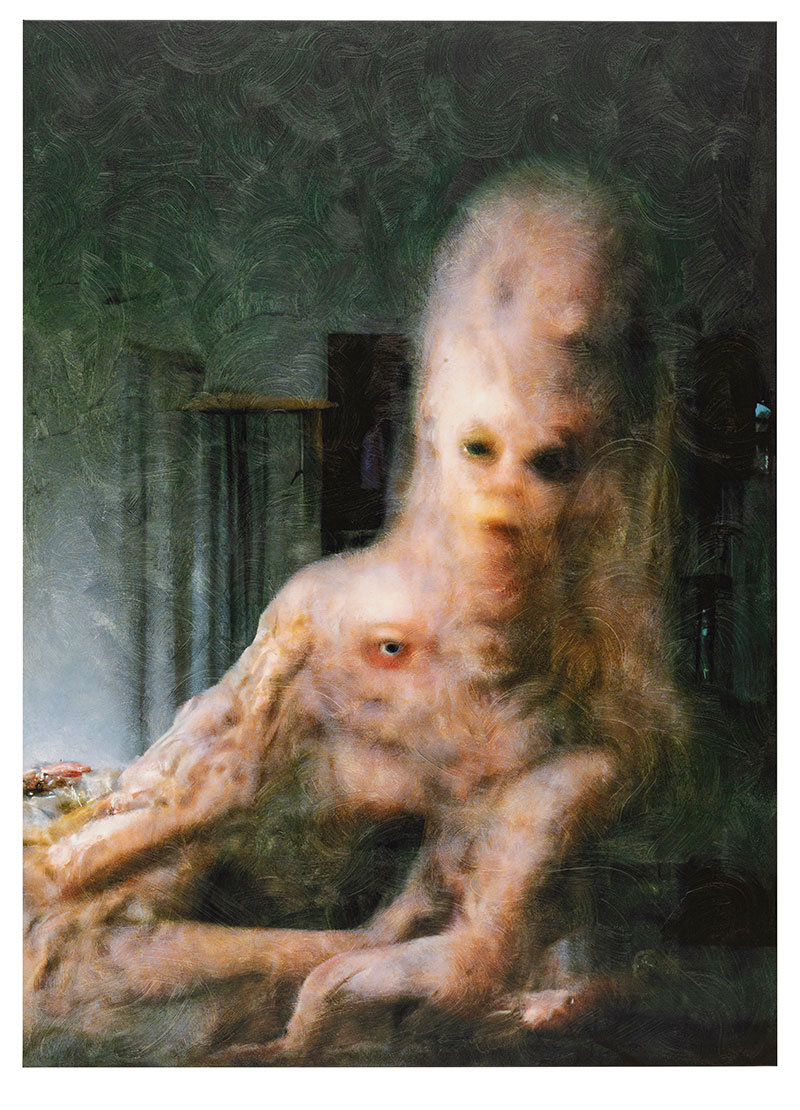

Jon Rafman: ‘𐤌𐤅𐤈𐤑𐤉𐤄𐤟𐤖 (Mutant 1),’ 2022, inkjet print and acrylic on canvas, 186.7 × 134.6 cm // Courtesy of the Artist and Sprüth Magers, photo by Etienne St. Denis

Among the characters encountered by the viewer was a diffuse brown blob with multiple eyes growing like a tree trunk from the bottom of the canvas, a fairy creature blending into the background of an impressionist forest, and a face composed of what appeared to be colored clay, vaguely reminiscent of Bob Dylan. The temple itself looked like it had been squatted by cyberpunks. The wallpaper depicted what appeared to be hallways full of computer servers, shiny and gleaming against a black backdrop. The ceiling was a pixelated vision of the heavens in yellow, white, and blue; on the floor burned digital hellfire. By exhibiting AI-generated works this way, Rafman’s show at Sprüth Magers asked crucial questions about how this new technology might transform our shared myths, in the process transforming our individual and collective identities themselves.

The portraits suggest that central to this transformation is the emergence of a new kind of representation that, even at the level of its production, belongs entirely to the intangible realm of the digital. In their content and materiality, these works stage a tension between a pre-modern notion of art as a uniquely human creation, and its existence as the product of an AI algorithm. As Rafman puts it, “the allure of the objecthood of the paintings is a romantic longing for a kind of art or experience that is potentially obsolete.” This tension between human and machine, concrete form and digital ether, is embedded in the materiality of the paintings, which after being generated by AI, are hand-painted and printed over on an ink-jet printer. It is also represented in the uncanny figures depicted in the paintings themselves. They are portraits of the posthuman reality that, with AI-generated art, has perhaps already arrived.

Jon Rafman: ‘Chapel,’ 2022, digital print on vinyl, LED, total width: 20.184m, total height: 3.81m // Courtesy of the Artist and Sprüth Magers, Photo by Timo Ohler

Like any epoch-defining technology, text-to-image AI has incited a considerable amount of utopian and dystopian punditry, from magazine articles praising its potential to unleash limitless human creativity to news reports claiming it will steal the jobs of working artists. Two claims are often made about the technology’s posthuman radicalness. The first is that text-to-image AI removes the skill from the creation of visual art, or at least displaces it. Artistic ability no longer rests in making works themselves, but in coding them: writing a text to produce a particular image. This, in all fairness, is more difficult than it sounds. Rafman suggests that every portrait in ‘Counterfeit Poast’ involved thousands of discarded attempts. The second claim is that this image itself is not new, or not a novel human creation at least, but an amalgamation of existing images in the dataset.

Practically the same can be said, of course, about photography, a technology that some would claim ushered in the era of modern art itself. The difference is that for photography, the skill doesn’t involve coding for an image, but perceiving and framing it in space. Claims to the image’s lack of novelty aren’t based on its preexistence in a digital dataset, but as an object in the physical world. These differences make photography and AI-generated images parallel aesthetic innovations. If photographic art stakes an exclusive, totalizing claim to the physical imaginary, then AI-generated art does the same for the immaterial domain of the digital. “Technologies like AI image generation open fresh territories where artists can reform previous aesthetic strategies to meet these new technological possibilities,” notes Rafman. “In doing so, a new culture is created, standards of aesthetic judgment and production are revised, and I hope questions about the broader historical implications of these developments are raised.”

Jon Rafman: ‘Counterfeit Poast,’ 2022, 4K stereo video, 23:39 min, film still // Courtesy of the Artist and Sprüth Magers

AI promises to extend the scope of our already-extensive digital experience. Rafman’s recent work uses AI technology to explore how this digital experience defines both our individual identity and, as shared experience, our sense of community. ‘Counterfeit Poast’s’ titular video installation assumes the form of a series of short films, in which voice actors narrate individualized stories of identity and alienation in a world transformed by these technologies. The narratives are inspired by postings on message boards such as Reddit, and visualized to uncanny effect using text-to-image AI. Many of the stories concern people who are convinced that they are their avatars: a boy who believes himself to be a walrus, a Texan man who is convinced he is actually a gay Somali pirate. For these individuals, the kind of imaginary identity they might assume in their digital lives—on Facebook and 4chan, GTA 5 and Second Life—has supplanted their physical selves.

Jon Rafman: ‘Counterfeit Poast,’ 2022, 4K stereo video, 23:39 min, film still // Courtesy of the Artist and Sprüth Magers

‘Punctured Sky’ (2021), a short film that still can be seen as part of his solo show ‘Ɛցɾҽցօɾҽʂ and Grimoires’ at the Schinkel Pavillon, also examines how our collective memory, as that which binds us together as a society, is changed by digital technologies. ‘Punctured Sky’ is digitally-animated cinema noir about two young men searching for a video game they remember playing as children, a game that seems to have disappeared from the face of the earth. The story is similar to one of the shorts in ‘Counterfeit Poast,’ in which a woman shares her absolute conviction that she has seen ‘The Traveling Salesman,’ an obscure film starring Kevin Costner as a salesman attacked by a roving band of Satanists in a post-apocalyptic America, despite the fact that no one else seems to remember it. In both of these stories, belief in the obscure cultural object is existential, the difference between the alienation of madness and participation in society. Such is the risk in a world where cultural objects and narratives proliferate in increasingly fragmented online communities, their existence erased in the flash of a hard drive. In furthering the digitization of culture, AI will undoubtedly further its precarity and fragmentation. Whether it has the potential to reorient culture in other ways remains to be seen, and is one of the questions looming before artists such as Rafman today.

Jon Rafman: ‘Punctured Sky,’ 2021, 4K video, sound, 21 min, video still // Courtesy the Artist and Sprüth Magers

If history is any indication, AI doesn’t mark the end of art, as alarmists might have us believe, but it does mark a profound shift. As before with photography, it is in all likelihood a keystone in a crucial moment of cultural transformation, perhaps even of society’s transformation itself. Rafman’s work points to potential aesthetics, narratives and identities that this emergent change might produce. The only thing clear at this point is that we are still at the nascent stage of artificial intelligence, perhaps comparable to the early daguerreotypes of the 1800s. The apex of its development is still to come.

Exhibition Info

Schinkel Pavillon

John Rafman: ‘Ɛցɾҽցօɾҽʂ and Grimoires ’

Exhibition: Sept. 15 2022-Jan. 22, 2023

schinkelpavillon.de

Oberwallstraße 32, 10117 Berlin, click here for map