by Matteo Calla // Apr. 4, 2023

How does a computer see the human face? The radical premise behind ‘Eigenface’—Ulrich Gebert’s latest show at KLEMM’S Berlin—is that computer vision sees the face as an artist does, that is, aesthetically. Like Harun Farocki’s landmark ‘Eye/Machine’ series, with its depiction of the automated ways of seeing guiding modern military technology, ‘Eigenface’ is shown from a computer’s perspective. The exhibition consists of a series of portraits hung on walls painted with a grid, often marked with the guidance lines seen in camera viewfinders and missile targeting systems. Many of these portraits assume the same frontal orientation and schema, and through digital and analog techniques have been rendered unrecognizable, absurd or disassembled into parts. Here, faces appear as forms, arranged into face-like patterns. The effect is disorienting and carnivalesque, like standing in a funhouse full of distorted selfies.

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of the artist and Klemm’s Berlin

This vision of the face as form and pattern—assumed by artists and computers alike—marks a break from humanism and the kind of portraiture seen during much of the 19th century. The humanist vision of the face is perhaps best articulated by French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who understood the face as a representation of our unique subjectivity as individuals. For Levinas, the human face is always more than its form and features, more than a person’s social or contextual role; it is what makes a person uniquely themselves and as the foundation of Levinas’ ethics, what makes us answerable to each other. Levinas’ humanism finds its visual correlate in realist portrait painting where, to be sure, the face is also an aesthetic form, but is representative of an individual human subject.

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of the artist and Klemm’s Berlin

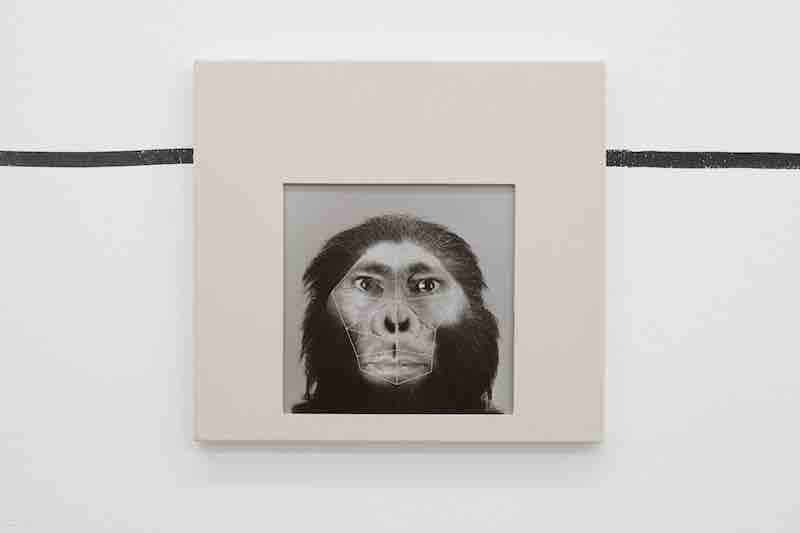

‘Eigenface’ rejects these humanist presuppositions. By treating the face as a set of formal features, the show blurs the lines between human subject, animal and object. The faces of apes figure prominently here, often granted uncanny and hilarious human expression through digital editing. Conversely, in ‘Eigenface (M),’ Gebert’s own face is split into two and edited to appear more ape-like. There are also inanimate faces (ape-like masks, an AI-generated face and what looks like the face of a puppet), all unified by appearing in the same general face-schema.

The viewer is left in a state of undecidability. Which face is human and which is an animal? Real or virtual? Subject or object? Above all, which face can I identify with? The show’s posthumanist vision of the face offers one way of understanding its title: what exactly constitutes our “Eigenface” (roughly translated as our own face) is being called into question here.

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of the artist and Klemm’s Berlin

‘Eigenface’ is also the name of a statistical method of facial recognition, developed in 1991 by Matthew Turk and Alex Pentland. In the ‘Eigenface’ method, a set of face images corresponding to the same general schema (frontal view, framed and lighted in a similar manner) are compiled to produce an average face and a numbered series of “eigenfaces” with statistically-significant differences in a particular facial feature. Any human face can be considered a weighted combination of these “eigenfaces,” and when a new face is presented for recognition, its own weights are compared to the database to find a match. The “eigenfaces” themselves appear quite uncanny: blurred out, spectral shadows of a human face.

For facial recognition then, computer vision is never just aesthetic vision. Rather, as Berlin-based artist and researcher Adam Harvey suggests in his essay ‘Computer Vision,’ facial recognition interprets and misinterprets the aesthetic and formal reality of an image, projecting onto it statistical assumptions of meaning. Facial recognition technology starts with an image of the face, but uses statistics to recognize and identify it, a process that is always probabilistic and never absolute.

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of the artist and Klemm’s Berlin

This is part, I think, of what makes many of us so uncomfortable with facial recognition technology. It is a perversion of the humanist vision of the face that, consciously or otherwise, many of us adhere to. For the humanist, the face is where we recognize each other most intimately as individual subjects and fellow human beings. Facial recognition technology grants computers this power of recognizing individuals. Yet a computer is incapable of recognizing a subject; it can only recognize the face as an object, a target, sorting it probabilistically into a category and box.

The portraits in ‘Eigenface’ are presented as the potential targets of facial recognition. They appear mostly from the frontal perspective and schema characteristic of “eigenfaces” (one image, ‘Eigenface (J),’ assumes the spectral form of an “eigenface” itself, albeit edited to appear ape-like) and are marked with guidance lines that appear throughout the show, echoed in the grid that lines the gallery walls.

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of the artist and Klemm’s Berlin

But just as Gerbert’s images subvert the humanistic vision of the face, so too do they subvert computer vision. The images are constructed in ways that thwart easy recognition and identification. Often, this is achieved by blurring the lines between animal and human expression. In one particularly funny image, guidance lines frame the remarkably face-shaped anus and tail of an animal.

Almost none of the portraits in ‘Eigenface’ are straightforwardly recognizable, and when we look closely at the grid lining the walls, we notice that the lines, too, are not painted straight. With ‘Eigenface,’ Gebert has created a series of images that at once mimic facial recognition and resist it. They harken back to some of his earlier photographs of animals and nature, such as the works collected in his 2012 book ‘A Rat is a Pig is a Dog is a Boy,’ in which an aesthetic of unrecognizability becomes a strategy of resistance to a human logic of categorization and capture. Neither human subjects nor objects, these images exist instead in an unassimilable in-between, one that Felix Ruhöfer—referring to Gebert’s work using philosopher Bruno Latour’s term—calls “quasi-objects.” Not wholly human nor wholly other, the portraits in ‘Eigenface’ hang silently on the walls, staring at us.

Exhibition Info

Klemm’s

Ulrich Gebert: ‘Eigenface’

Exhibition: Mar. 3–Apr. 15, 2023

klemms-berlin.com

Prinzessinnenstraße 29, 10969 Berlin, click here for map