by Hans Carlsson // Apr. 28, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Money.

On December 6th, 2022 the news was released that the artist duo Goldin+Senneby were requesting 2,274,068 Swedish Krona (approximately 200,000 Euros) as compensation from the Swedish Transport Administration and the Public Art Agency Sweden after these authorities withdrew from an agreement to buy the artist duo’s piece ‘Eternal Employment.’

It was in 2017 that the Goldin+Senneby work was commissioned as a public artwork for a planned train station at Korsvägen in Gothenburg. The proposal would take the form of an eternal performance, where someone (hired from a public job announcement) would get a full time position working at the station. On Goldin+Senneby’s website, the job was described as follows: “The position holds no duties or responsibilities, other than that the employee is expected to check-in and check-out at the Korsvägen train station at the beginning and end of each working day. Whatever the employee chooses to do constitutes the work.”

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Eternal Employment,’ detail from proposal: “working light”, 2017. Commissioner: Public Art Agency Sweden & The Swedish Transport Administration // Visualization by Anna Heymowska

The financial plan for paying the salary of the employed person for an indefinite period of time was supposed to be financed with the profit resulting from investing the entire project budget (7 million Krona) in the stock market.

In its planning stages, the proposed piece caused a stir in Swedish and international media. Some accepted it as a truly radical way of investing public art money, both because of the work’s symbolic critical qualities underlining the fact that “money pays better than work” and also because of Goldin+Senneby’s gesture of leaving room for someone to, so to speak, “fill the gap” of artistic intention left out by the artists.

Others, however, grasped the whole project as extremely cynical. The harshest of all critics was perhaps the Editor-in-Chief of the Swedish part of the online art magazine Kunstkritikk, Frans Josef Peterson, who wrote—in an exchange with the director of the Public Art Agency, Magdalena Malm, who embraced the project throughout the process—”What idea of public art should we think the proposal manifests? Should we have employer art now?” For Peterson, the fact that Malm let investment funds (ruled by market forces) control how and what art should be presented in public space was nothing less than a betrayal of a democratic idea that public art institutions should provide art for everybody.

It seems rather unlikely that Goldin+Senneby’s proposal will actually be materialised in 2026, as it was originally planned. And this is not because of the criticism the project has already received, but because of a bureaucratic detail that prohibited the governmental institutions involved from proceeding with the project. It was the transport administration that stopped the project, claiming that the public art agency is not allowed, according to Swedish law, to give out money that should finance art projects to a foundation (Goldin+Senneby started one to be able to pay the future employee in an organised way).

In other words, bureaucracy stopped the artistic outsourcing planned by Goldin+Senneby. And it did so in an unpredictable way, since ‘Eternal Employment’ activated the governmental control of capitalist intervention into public money sectors. One could actually say, as Peterson also pointed out in his critique of the piece, that as a result, the never-produced artwork gained more layers of complexity.

Goldin+Senneby, lecture at e-flux, New York // Courtesy of the artists

Goldin+Senneby’s practice relates to a conceptual mode of art-making. They produce idea-based pieces that are often executed by someone else. For me, there are very clear links between the acclaimed duo’s practice and canonised conceptual artworks, such as Sol Le Witt’s wall drawing pieces, made by institutional staff all over the world, following the artist’s descriptions. Goldin+Senneby’s work also evokes art practices making use of conceptual strategies to intervene and aesthetise economic and bureaucratic processes. John Latham and Barbara Steveni’s London-based Artist Placement Group from the 1960s–80s, which aimed to make artists transfer their practice to the bureaucratic and economic processes of public institutions and private companies, comes to mind.

Another similarity between Goldin+Senneby’s conceptual method and earlier precursors is that there exists a discrepancy between the conceptual and the visual. The aesthetics of Goldin+Senneby have often oscillated between an almost ironic copying of corporate, or work aesthetics, and a symbolically overloaded sculptural and installation-based practice. These are expressions that are not seldom combined with didactic material such as recorded lectures, long texts or slideshows, which explain the project’s background.

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Banca Rotta’ with Anna Heymowska (set designer), 2012 // Courtesy of the artists, CFHILL Stockholm and NOME Berlin, photo by Björn Petrén

A good example of the duo’s use of work aesthetics is the proposed design of the train station in ‘Eternal Employment’: a time clock for the worker to check in with, fluorescent “office” lights and a changing room that only the employee has access to. A signature example of the overloaded symbolic sculptural side of their practice is, on the other hand, the broken renaissance money changer’s table, cut in two pieces, that the duo has shown at several venues. The title of the piece, ‘Banca Rotta’ is Italian for broken bench, and the etymological source of the word “bankruptcy,” which derives from banca rotta. Historically, Italian moneylenders had to destroy their working desks when they went bankrupt.

Goldin+Senneby’s authorless engagement does, however, say something about the world we live in, applied as it has been to digitised and ultra-capitalist structures governing so much of human life on this planet. In 2017, one could view their piece ‘Force Directed Predictions with artificial intelligence by XLabs.ai, David Layton, Drs. Radhika and Travis Dirks’ at NOME Gallery in Berlin. Two printed, colorful neon lumps floating around on a black background, visualising an artificial intelligence software’s attempt at learning to predict how art prize fluctuations depend on macro-political and economic factors (for example, employment rate and literacy).

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Force Directed Predictions: Art Contradicts Employment with artificial intelligence by XLabs.ai, David Layton, Drs. Radhika and Travis Dirks,’ 2017 // Courtesy of the artists, CFHILL Stockholm and NOME Berlin, photo by Björn Petrén

In recent years, Goldin+Senneby have expanded the arsenal of outsourced project participants to not only include ghostwriters and algorithms, but also new collaborators like microorganisms and trees. In a new artistic public artwork, this time planned to be executed just outside a ten-storey hospital building, currently under construction in Malmö, Goldin+Senneby has proposed to clone a “spruce on Furufjäll mountain in the central Swedish county of Dalarna.” The clone of the tree, which is the oldest in the world because of its root system dating back to over 8000 years BC, will be presented in a climate-controlled greenhouse (connected to the excess cooling capacity of the hospital)—a care building, keeping the clone alive, like a customized miniature hospital responsible for the health of this single species.

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Spruce Time,’ production still: grafting scion from Old Tjikko onto rootstock, 2020 // Commissioner: Malmö Hospital, Region Skåne, photo by Henrik Lund Jørgensen

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Spruce Time,’ location sketch by Johan Hjerpe (graphic designer), 2022 // Commissioner: Malmö Hospital, Region Skåne, photo by Nilsmagnus Sköld

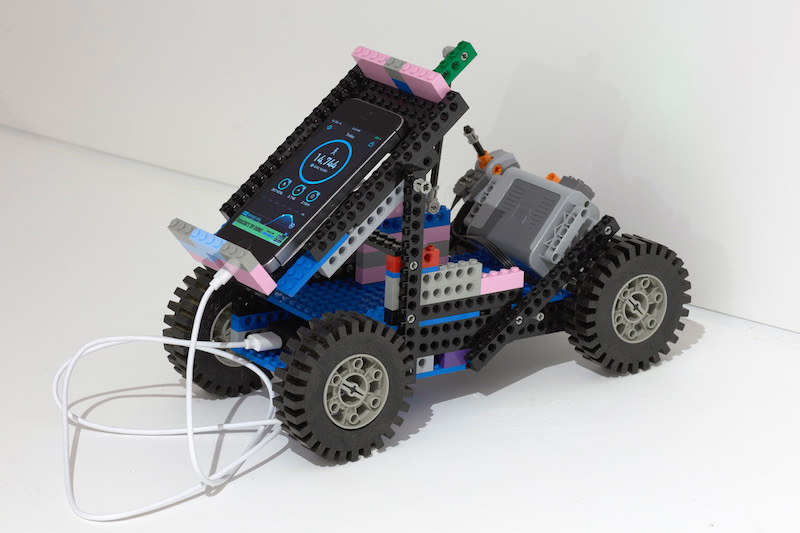

The interest in plants, microorganisms and other non-human species was also visible in the exhibition ‘Insurgency of Life’ at e-flux in New York, where the funghi Isaria sinclairii was cultivated in a stainless steel pool. Isaria sinclairii is normally used as the active ingredient in the medicine Gilenya, taken for Multiple Sclerosis, which Jakob Senneby of Goldin+Senneby has suffered from since 1999. The pool was exhibited together with Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting ‘Fountain of Youth’ from 1546, where elderly people descend into a rectangular pool to re-achieve their youth in a forest and mountain landscape. Together with this, there were also car-like lego robots carrying around smartphones counting the “steps” this machine took.

In her brilliant e-flux essay on this exhibition, ’What Is Wrong with My Nose: From Gogol and Freud to Goldin+Senneby (via Haraway)’, the curator Maria Lind writes that Senneby participated in a survey by the medicine company Novartis, to study the effect of the first MS treatment for oral consumption at home—a possibly dangerous task that the artist was not compensated for. The false-stepping lego robots in the exhibition were meant to trick medical companies, who are constantly trying to harvest data to achieve information from our bodies without paying for it (and transforming this data into medicine and care in a profit-driven sector).

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Insurgency of Life (Lego Pedometer Cheating Machine),’ 2019, installed at e-flux, New York, 2019 // Courtesy of the artists and NOME Berlin, photo by Gustavo Murillo Fernández-Valdés

Lind finds something deeply personal, intimate and bodily in these new works by Goldin+Senneby. She suggests that the duo, by consciously leaving out what they are thematising (namely, the body itself), underlines how we are constantly reconfigured by outside forces perforating our flesh, such as the market economy, medical experimentation and algorithms both controlling and achieving information from us. While commenting on the habitual outsourcing of artistic labour by Goldin+Senneby, Lind notes that something has happened: “While they [G+S] still outsource many tasks, with time, their service providers have become more like collaborators.”

What I find appealing in these new works by Goldin+Senneby is that they do not rely as much on irony and mimicry, as on lack and fragility. The duo, in these recent pieces, leaves the conceptually illustrative behind, to instead explore the expressive and affectively-charged.

Goldin+Senneby: ‘Insurgency of Life’ with Anna Heymowksa (set designer), Amanda Selinder (biohacker/artist), Ross McBee (biologist), Hans Hertz Lab (X-ray physics), 2019, installed at NOME, Berlin, 2021 // Photo by Billie Clarken

It’s easy to understand that the lonely spruce tree in the greenhouse, exposed to the world but kept alive by Frankenstein-like machinery, might not live such a happy life after all. Likewise, the introduction of companion species such as the Isaria sinclairii funghi is both a reminder of the unavoidable ecological backbone of human existence, and the extremely sad and cynical fact that these living creatures, as well as humans themselves, are nothing but exchangeable entities in the eyes of the market. Gone is the clever metaphorical or symbolic use of shiny corporate aesthetics or the witty metaphorical sculptures, and in its place we find a language that might just address a common grief, one that can hopefully lead to action.