by Alison Hugill // May 5, 2023

Epithets used to describe an artist’s standing within the market—like emerging or established, early-, mid- or late-career—may seem neutral and objective in language, but they carry with them the weight of an economic and social system that is full of violent contradiction, especially when it comes to aging. On the one hand, emergence and being “early” in one’s career suggest that one has not yet learned the tricks of the trade and is still impressionable. Being established or late in one’s career, on the other hand, suggests a certain refinement and savoir faire. And yet arts funding tends to target the young, ostensibly banking on their imminent futurity. Anyone who doesn’t fit tidily into these binary poles of categorization, which are primarily defined by an ageist system that financially rewards youth and socially valorizes those who have managed to “stay in the game,” might find themselves at sea. What happens if you’re not young but also not established? Mid-career but still emergent?

In an essay entitled ‘Beginning, Middle (Age), End: Script Notes and Revisions,’ published by Coven Berlin, artist Melanie Jame Wolf eloquently considers the ageism underpinning all fields of work, from sex work to art practice and far beyond. Most often, this ageism has a misogynistic overtone, and is directed, as Wolf notes, at the those who fail to fit into a schema of “desirability” perpetuated by the white male gaze. She writes: “I arrived at my career as an artist ‘late.’ People do. My failure to be ‘on time’ has been a constant source of anxiety. Each 30 under 30 list. Each call out for young artists. Each ‘artists up to the age of 40 may apply.’ Each request for a date of birth on an application form or a catalogue bio. Each of these things tells people who have been occupied elsewhere—with care work, or in prison, or overcoming abuse, or addiction, or generally attempting to pull themselves and others out from under structural oppressions, or just fucking living—that they have failed to pass the white bourgeois milestones of decisive vocation, institutional training, unpaid internships, and emergent successes in a timely, respectable fashion. They are temporal deviants. And deviance does not go unpunished by The Gaze.”

Liz Magor: ‘Oilmen’s Bonspiel,’ 2017, Focal Point Gallery installation view // Photo by Anna Lukala, courtesy of the artist and Focal Point

In an interview for this topic, I spoke with Canadian artist Liz Magor, who has surpassed this tricky and uncertain period of “middle age” or “mid-career” to reach the coveted status of established, late-career artist. Unlike some of her peers, she has attained this position quietly, without major fanfare. Though our conversation largely revolved around aging on the level of found materials and preservation in her work, she asserted that being able to access a well-spring of intuition and self-knowledge in her practice has been a gift afforded with age. And it’s one that she is clear to note comes with no small amount of privilege. In her words, “it’s hard to have a complicated life as an artist.” Wolf’s aforementioned list of barriers to a long career in the arts, which includes “just fucking living,” should stand as a reminder that the precarious nature of work in the art world acts as its own kind of elimination system.

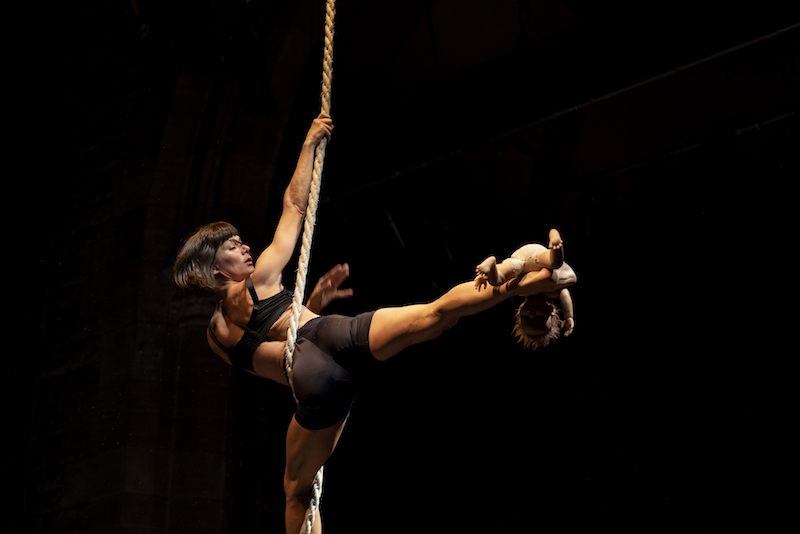

Still Hungry: ‘RAVEN,’ 2022 // Photo by Billie Wilson Coffey

Among the myriad elimination criteria is also care work. In an upcoming interview by Anna Roos van Wijngaarden, performer Romy Seibt talks about her recent collaborative theater piece ‘RAVEN,’ which interrogates the German term “Rabenmütter,” denoting a bad, uncaring or unnatural mother. Exploring the dark sides of their own parenting journey, Seibt’s collective Still Hungry muses on the effects of aging and how the physical and mental changes that come along with motherhood affect artistic practice, particularly in movement and performance-based work. If an artist prioritizes her career, she is a bad mother. If she prioritizes her child and doesn’t make enough work or money, she’s a bad mother and a bad artist. There’s no winning.

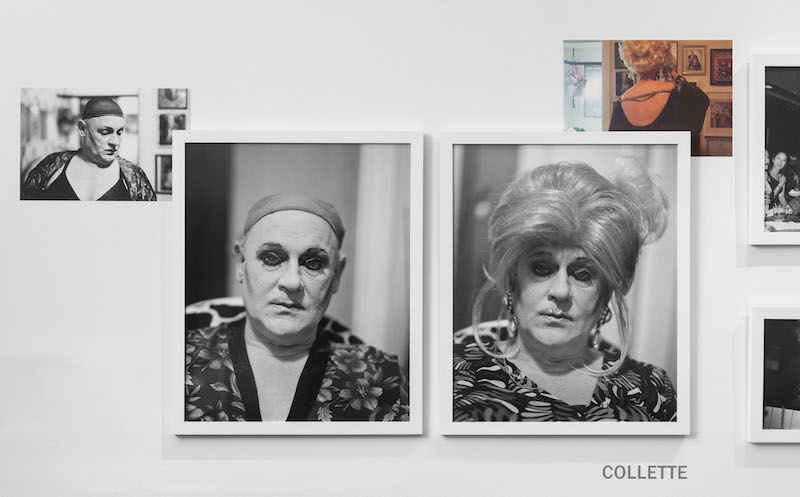

In many queer communities, aging is often seen an act of defiance against a system that actively devalues queer life. Photographer James Hosking recently shot a series of photos and a documentary film entitled ‘Beautiful By Night,’ which looks at drag performers in a San Francisco gay bar. The performers that drew his attention were the elders of the group, and in our upcoming interview, Hosking explains: “I explore their transformations at home, backstage and onstage, engaging with liminal states that transcend gender and beauty conventions. As I progressed, the series’ primary themes coalesced around aging, identity and labor.”

James Hosking: Detail view of ‘Collette’ wall (installation photo), 2021, framed archival pigment prints and archival pigment prints on adhesive photo tex, dimensions variable, pictured 36” x 67”, 2013-2015 // Courtesy the artist

One thing we learn from these diverse perspectives on artistic practice is that aging is a verb, a process: there is no singular way to age. The art world’s expectation of a point A to B career trajectory, despite a host of potential structural barriers, is especially unrealistic considering the lack of support it affords those no longer in their youth. At the same time, on a personal level, aging can bring with it a clearer sense of self and serve as a marker of resistance against the forces that threaten survival, especially in queer communities where elders have, until recently, tended to be rare.

On the level of the artwork itself, the art market and museums have solidified a host of different preservation methods, thus valuing the aging process of certain media and materials over others. The intertwined nature of age and value, whether for better or worse, is a constant preoccupation of the art market. With this topic, we aim to shed critical light on some of these long-held allegiances, drawing attention to the ways in which artists and artworks manage to question or actively overturn them.