by Annalisa Giacinti, studio photos by Curtis Hughes // May 12, 2023

It’s a rainy morning and Kreuzberg is unusually quiet. The sparse traffic noises are muffled by the almost imperceptible sound of a light drizzle. Chloé Lee’s studio is located in a calm residential street on the top floor of an apartment building, and it overlooks a tree-lined courtyard. Despite it being a rather cool early April day, the greenery looks lush and of a beaming green, hinting at the much awaited nearing of spring.

The green from outside continues indoors, sneaking into Lee’s studio. Her desk faces a wide window, and is framed by various house plants that stand next to a small pile of books and notebooks, a MIDI Player and her working computer. As we step in, she welcomes us with a cup of flowery green tea, while the warm and soothing voice of Nina Simone plays in the background. The atmosphere is cosy and intimate, for Lee’s working space is also where she lives: her creations blend with her personal belongings, or appear to be their natural extension. Two framed pictures of her parents stand in the middle of a shelf alongside books, sketches and the technological gear she uses in her practice, which is kept next to wine glasses and kitchen items. It’s a set-up that fittingly prefaces the deeply personal substance of her project.

Chloé Lee is an Asian-American artist whose work stands at the intersection of digital and analog, both relying on the use of colour, collage and drawing, as well as 3D and virtual reality technologies. A graduate in Integrated Media Arts and a freelance filmmaker and producer, Lee was becoming acquainted with said techniques in 2020, when the pandemic hindered the possibility to work within the physical space of a real gallery and brought about a phase of introspection and (inevitable) isolation. It was then, when the real world was being shut down, that she got herself a headset and decided to turn to virtual ones, experimenting with their escapist and meaning-making potential; exploring memory and identity, and unknowingly conceiving what would soon become ‘Temporal World.’ A year later, in 2021, Lee was granted a Creative Arts Fulbright scholarship to develop her project, then called ‘Memory Palace,’ and flew to Berlin to start an open-ended collaboration with research group Matters of Activity, Humboldt University and DGF (German Research Foundation).

Before Berlin, Lee had lived in New York City for ten years but visited Singapore regularly, where her mum is from and her grandma still lived. As she began reflecting on family heritage, she decided to stay in the country for a month to do research on its rapid urbanisation and consequential issues concerning historical preservation. She spoke to locals and recorded contrasting opinions about the fast-changing appearance of the city: some people were nostalgic, dissatisfied, whereas others managed to creatively exploit the process by way of preserving spaces but reinterpreting and bestowing on them a new function. “I was interested in the question of preserving the essence and meaning that these places represented in the landscapes that were no longer there,” explains Lee.

A similar contradiction forms the underlying theme of her current project too: VR, the gaming industry and technology tout court represent the need for progress and innovation, so employing it to explore memory seemed to Lee an interesting paradox to start from, one which would later unearth several others. Indeed, ‘Temporal World’ reflects on memory of places, the varying levels of connection and disconnection to these, and constant fluctuations between the two sentiments. New York is the city where she lived for ten years and spent most of her adult life, the place she thought she’d never leave and felt the deepest connection to, until one morning she woke up in Berlin. Here, Lee experienced a feeling of displacement that reconnected her to her migration background and ancestral roots in China and Singapore. In regard to the productivity of the unexpected, in the place of origin of her Chinese grandparents, from her father’s side, where she only ever spent three hours in total, she recounts that “it felt pivotal and determining to how I came into the world, almost archeological.”

Once in Berlin, from September until July 2022, she conducted research at the Institute and became exposed to different disciplines by working alongside physicists, anthropologists and other artists, enhancing her knowledge in VR and learning about haptic technology. ‘Antennae’ was Lee’s first exposure to VR: a collaboration with Samuel Perea-Diaz and Vanta exhibited at the Tieranatomisches Theater, for which she 3D modelled/printed a custom plate to mount speakers to the outside of a headset, and it kicked off her exploration into generative sound. All the while, Lee was reading, writing and wandering around the new city attempting to root herself in it. In July, she began working with developer Lucas Martinic to make the project interactive, until ‘Temporal World’ was first shown to the public at Silent Green in January 2023.

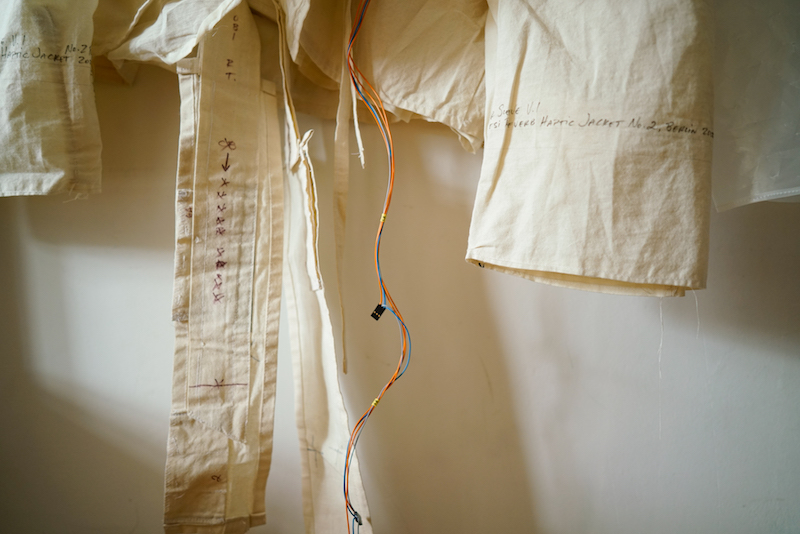

Lee lets me try the experience and get a glimpse of the virtual world she created. Snippets of more or less familiar landscapes appear when I put on the headset, and her subdued voice guides me through them, mixed with noises and sounds collected through field recordings and music she composed on the MIDI player. In addition to the headset, which would provide the typical VR audiovisual experience, I get to wear a haptic jacket so that this adventure acquires a whole new physical layer. Lee shows me sketches of the jacket and explains it was designed in collaboration with fashion designer Dru Blumensheid, and based on the ‘Haptic Hanbok,’ a project inspired by the traditional Korean garment and developed by Fardin Gholami, Yoonha Kim and Maxime Le Calvé for the exhibition ‘Stretching Materialities.’ Lee and Blumensheid worked together to create a jacket “that is tech but you wouldn’t expect it to be.” Indeed, it is made of 100% cotton and structured through a double layer system that hides the inner wiring and makes it look like a totally wearable piece of summer clothing. Moreover, its lining displays a photo-texture from China, of her family’s ancestral home and one of the places that can be experienced in her work. “It’s space that’s inside, against your body, yet you can’t see it,” she says.

The wired lining of the jacket translates the sound generated in the headset into a vibrational feedback that is sent to my body. At the same time, Lee tracks my movements on the computer through a histogram, a tool for frequency visualisation that allows her to know which sound will be played on which part of my body by recognising the range of frequency assigned to a specific motor in the jacket. I am also given a set of virtual hands that help me travel across this immersive space. This way my body can shift the sound and provoke visual changes too, determining to an extent what I get to see and hear, and giving me an impression of agency that feels reassuring amongst the fragmented and ephemeral surroundings.

My virtual journey ends when the temporal world crumbles away. I take off the goggles and land back in Lee’s Kreuzberg studio, feeling slightly unsettled. The experience itself is not a cumbersome one, but it yields a bodily sense of wistfulness and yearning. Each pixelated image I came across (which was 3D-scanned from Lee’s personal archive) dissolved and glided away into darkness. The sound of Ismail’s flute, people’s chatter at the dinner table, the familiar U-Bahn track, a Hoisan lemon—none of it is visible any longer yet not fully gone either. “Everything leaves a little bit of a trace,” says Chloé Lee, and her work quite poignantly proves it.