by Anna Roos van Wijngaarden // May 19, 2023

STILL HUNGRY—a collective consisting of artists Romy Seibt, Anke van Engelshoven and Lena Ries—questions conservative assumptions around motherhood or, rather, the condemnation of “bad moms.” In Germany, the term “Rabenmütter,” denoting an uncaring or unnatural mother, has become commonplace.

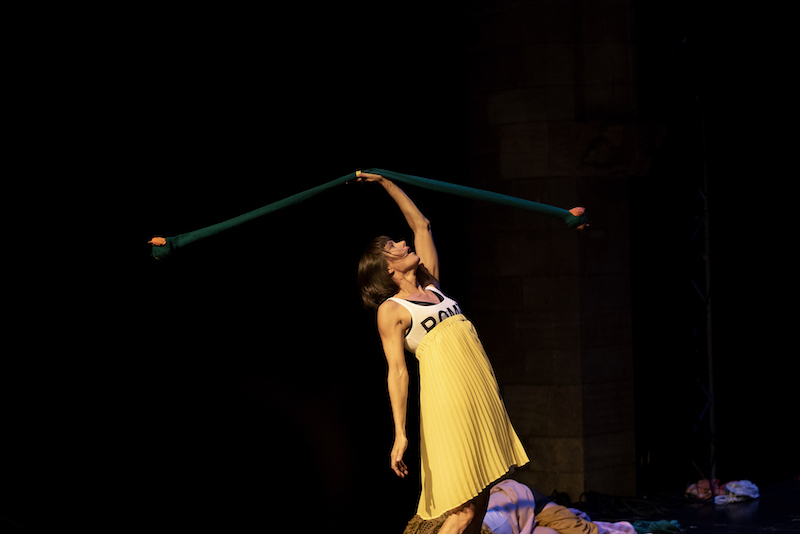

In the trio’s theatre play with contemporary circus elements, entitled ‘RAVEN,’ the bad mother is afforded the space to move freely across the stage. Directed by British live artist Bryony Kimmings, who is known for her emotionally intelligent and provocative style, the piece confronts its audience with all the conflicting feelings provoked by certain so-called “bad choices”: shame, restlessness, weakness, but also wildness, adventurism and assertiveness. Both in the play and in real life, the artists are mothers as much as they are passionate career women. And they’re not willing to give that up: they’re still hungry. We spoke to artist Romy Seibt about what that looks like and how it feels.

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Gianluca Quaranta

Anna Roos van Wijngaarden: ‘RAVEN’ centers around the German stereotype of the “Rabenmütter.” Does the piece try to fight against or change its meaning? How did you see your different audiences react to it?

Romy Seibt: Only in Germany do we have this special term for a bad mother, but it doesn’t make a difference, because we always describe it in the beginning of the show. People can relate, even when we perform it in a country like Sweden, where parenting is more communal. Whether you’re an artist on stage, a painter, or a sculptor, becoming a mother just changes your life. It changes the reflection on your life and how you’re seen by other people. Suddenly, your own parents say “maybe you should look for a more stable job.” And friends encourage you to “just be a mother now.” For fathers, I feel it’s not the same. You stay in your career. Moms, however, have to become responsible and have to change, and that touches the hearts of the audience.

Our characters have all these bad feelings, which come from accusations and arguments in their own heads: I want to remain an artist, I want to be a good mom. You feel bad because you arrive a few minutes late to pick up your kid, or maybe you didn’t earn enough money this month. These things kill you, mentally. So, in the end, we become ravens on stage. And we become friends. We alter things a little bit and say: people call us bad mothers rather than great artists, no matter what. We have to try to accept this, and not to fight it anymore. We fly around and try to remain as strong as we were before, enjoying the wildness, eager to keep this part of ourselves alive.

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Billie Wilson Coffey

ARW: Would you say the core of the piece is to make the audience aware of the consequences of these accusations, rather than to attack the concept of bad motherhood per se?

RS: Absolutely. We want people to think about what happens after their judgements, because it does something to you as an artist. Accusations about your failing motherhood make you feel unsure. You start to feel like you can’t do it anymore. Maybe I shouldn’t apply for that job after all. Maybe I won’t go there. It kills the confidence you had before. We talk about that after the show, and no matter if it’s fathers, mothers or women without children, many of them say: “what you’re talking about on stage is so important.”

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Billie Wilson Coffey

ARW: The “bad mothers” in the play go through a full range of emotions. How do movement, stage design and props help translating these different moods?

RS: When women become good mothers, you call them “hens,” and then you have the opposite, the raven mother. For the in between, we’ve collected other birds that stand for something. For example, the eagle is about freedom and independence. So, in the beginning, you see straps hanging down on different heights and Anke grabs those to spin really, really hard. She wrote a piece of text and while she is turning and twisting, you hear her voice. The music is slowly coming in. She’s talking about how it was: “I used to be an eagle, when I was going out dancing and getting touched by people, not knowing where the night would lead.” She’s clubbing on stage, while smoking a cigarette. She talks about her 20s and all those crazy feelings of getting lost and connecting with strangers.

Another scene we call parrots, because you train the bird to say words he doesn’t even know the meaning of. You see the three of us sitting on a sofa and you hear all the accusations—all the stuff that people have repeatedly said to us—in our own voices. We are talking to ourselves, but the content came from somebody else. Like my mother: “you’re never at home, no wonder that he looks for somebody else.” When you’re pregnant, people have the feeling they know better or can decide things for you. They come in and talk to your belly: can I touch it? At the playground, other mothers or fathers tell you what your baby “should be doing by now.” Sometimes you just want to stop the repetition.

As for props and the set, there is a laundry scene where I am trapped in a cage and going mental. When you have two kids, you have to do laundry every freaking day. It never stops. So, we created a laundry setting where I start to improvise with the meteor, a rope you can use to perform tricks. By juggling with the laundry, I bring my artistic world into a motherhood context.

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Daniel Porsdorf

AR: Despite the serious tone of the piece, humor plays a big part. How does it show throughout the performance and why is it important for communicating the message?

RS: There are lots of funny, small moments that get the audience to connect. For instance, at some point we become stupid hens: the cliché of a good mother. We tried to make this really voguing choreography and you hear the American 50s song ‘Pickin a chicken’ by Eve Boswell. Slowly, we become more and more bitchy. At some point I don’t have any milk left and take a bottle, and the other two are giving each other this look. We battle and do tricks with our babies. Later on, we lose our colorful clothes until we only have basic t-shirts with our names on them. We don’t wear any make-up. We look like “mother bros.”

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Daniel Porsdorf

ARW: You formed STILL HUNGRY to spread a message about careers and motherhood. What is your personal take on the story?

RS: When we founded out our company back in 2017, the name just came to us. It’s from a piece of graffiti that says “Still Hungry.” We were all already mothers and that was our feeling, like we want to do another show despite all the difficulties. It had to be about us and exactly about these difficulties. We wanted deepness and authenticity, but also to look for funny moments.

STILL HUNGRY: ‘RAVEN’ // Photo by Billie Wilson Coffey

ARW: The play contains elements of the contemporary circus. How do you see the future of this genre evolving?

RS: It’s a really big movement that came from France, the “cirque nouveau.” It’s been around for over 30 years in France, because they love the circus and wanted to move away from the classical ideas, like “here is the strongest man in the world” and “look what this beautiful woman can do.” Germany’s circus has been really traditional, with animals and tiny little costumes. But now we also use the term “neue Zirkus” for something that involves actors, musicians and circus artists. You use some of the high-end circus elements, combining them with talking and movement, whatever you need to tell the story.

For instance, after the scene of the parrots where we bear all these accusations, Lena is left alone on the sofa feeling really bad. She stands up looking at her body, lifting her skin and saying “oh my god.” As a contortionist, she is really bendy and stretchy, so she uses these skills to examine herself in really different ways, which is funny, but also sad. Her body has changed after giving birth to two kids. This is not an aesthetically pleasing dance. It is real.